Text of the interview by Giovanni Ghisalberti

The “good retirement” of the combat doctor

“A ‘Good Retirement’ a place to rest, in tranquility, but above all where he can continue working, to do what he has done all his life. Perhaps few people know it, but the Brembana Valley, for about twenty years, has had an illustrious guest, who has chosen our land to “take refuge”, a place from which its battle is still going on.

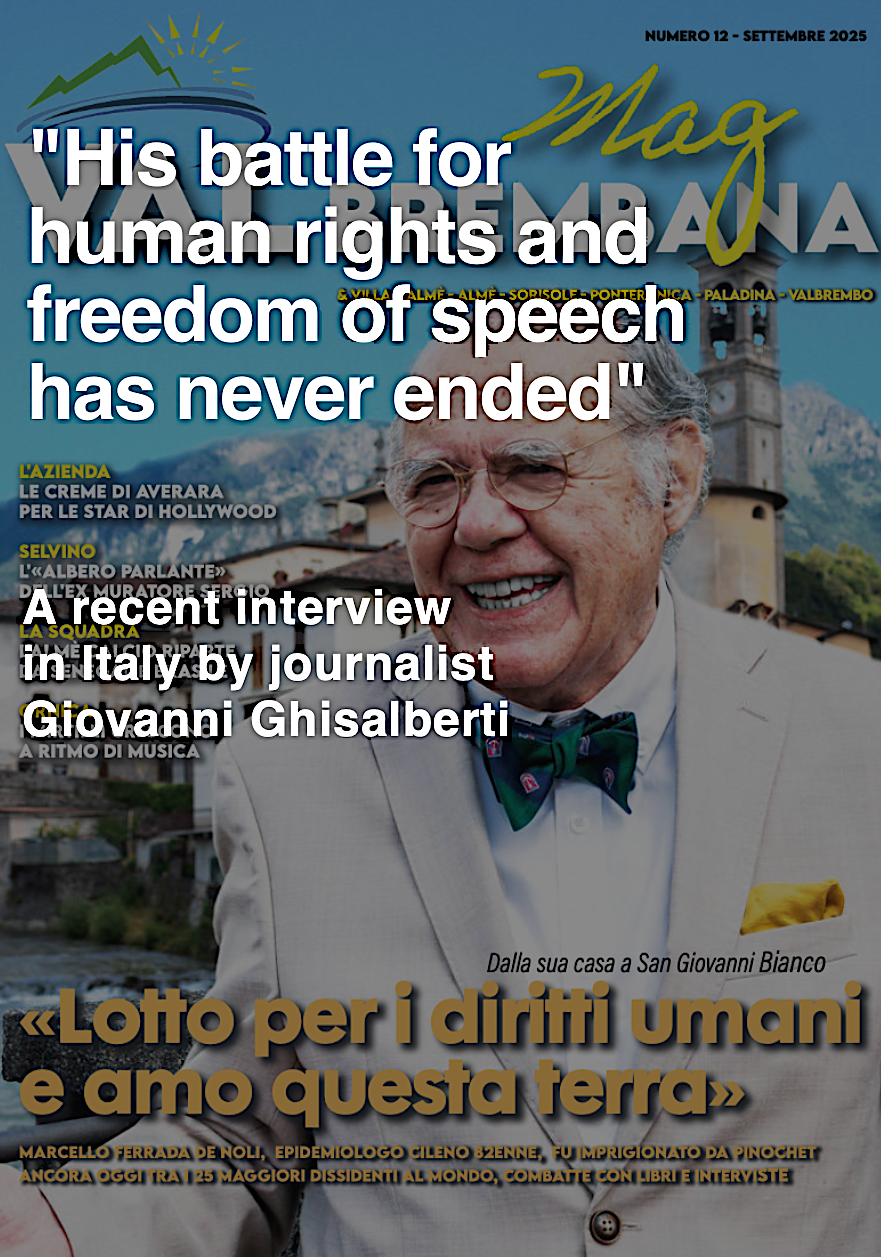

This is Marcello Vittorio Ferrada de Noli (his surname reveals the ancient descendants of the Genoese navigator Antonio, discoverer of Cape Verde), 82 years old, Chilean, one of the participants of the Resistance against Pinochet’s dictatorship in the seventies.

In Ernesto Che Guevara’s Cuba he received military training (at the age of 20), and at the age of 22 he was one of the founders of the Movement of the Revolutionary Left in Chile. After Pinochet’s coup, he was arrested and imprisoned on an island, along with other dissidents. A fighter, but also an internationally renowned epidemiologist, with his main research published during his teaching at Harvard (Boston – United States).

Even after his release, his battle for human rights and freedom of speech has never ended, with interviews and publications on radio and television. So much, that some magazines still list him among the world’s leading dissidents. A commitment that continues from the Brembana Valley, a land that was of great resistance to Nazi-fascism. “I love this land,” he says, “it’s quiet, there’s no tourist invasion.”

Doctor, fighter, but also artist, as evidenced by the paintings of his house, walls and antique furniture from the nineteenth century, in the Piazzalunga di San Giovanni Bianco. A home that, perhaps, few of us could choose as a residence. However, he also fell in love with this old house with its tall patina-peeling dome and wooden stairs from the past. From here, from the Brembana Valley, he leads his battles for freedom of expression. A lesson also for all of us and for how much our valley should be appreciated.”

/Giovanni Ghisalberti.

“I continue the struggle for human rights from the Bremana Valley”

“But what is an internationally renowned epidemiologist, psychiatrist, Swedish academic, artist, and a man who was one of the participants in the resistance to Pinochet’s dictatorship in Chile, and who is known in the world for his defence of human rights, doing in San Giovanni Bianco, for twenty years?

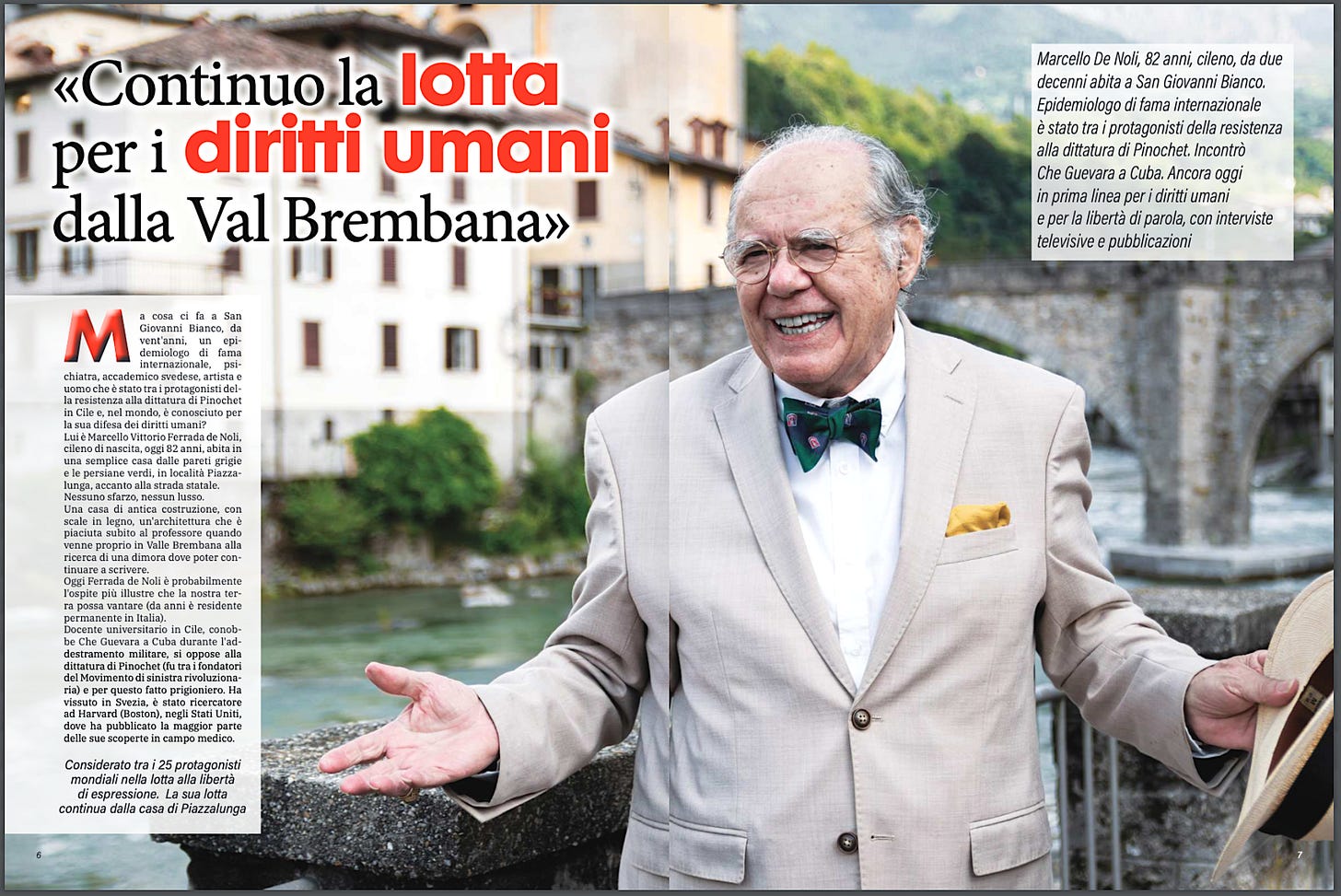

He is Marcello Vittorio Ferrada de Noli, Chilean by birth, now 82 years old, he lives in a unique house with grey walls and green shutters, in Piazzalunga, near the old provincial road.

No ostentation, no pomp. A mansion of very ancient construction, from the end of the 1600s. With wooden stairs, and with an architecture that the professor liked immediately when he arrived precisely in the Brembana Valley in search of a home where he could continue writing.

Today Ferrada de Noli is probably the most illustrious guest that our land can boast of (for years he has been a permanent resident in Italy).

A university professor in Chile, he met Che Guevara in Cuba during military training, opposed Pinochet’s dictatorship (he was one of the founders of the Revolutionary Left Movement) and, for that, was taken prisoner. He lived in Sweden, was a researcher at Harvard Medical School (Boston), in the United States, where he published most of his discoveries in the field of medicine.

Considered among the 25 world protagonists in the fight for freedom of expression. Their struggle continues from the house in Piazzalunga.”

«Marcello De Noli, 82 years old, Chilean by birth, lives since two decades in San Giovanni Bianco. Internationally renowned epidemiologist, he has been among the protagonists of the Resistance against the Pinochet dictatorship. In Cuba he met Che Guevara. Even today, he is on the front lines of the fight for human rights and freedom of speech, with television interviews and publications».

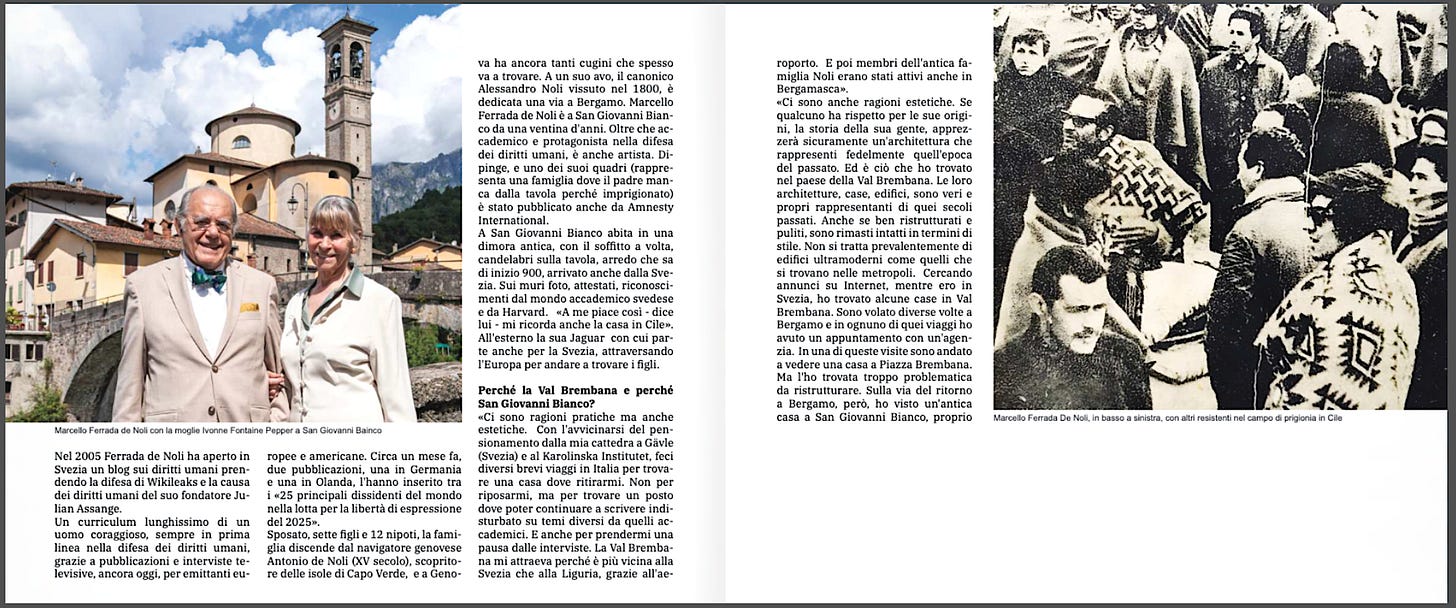

[Caption in photos above: 1) At left: Marcello Ferrada de Noli with wife Ivonne Fontaine Pepper 2) At right: “Marcello Ferrada De Noli, below left, with other resisters in the prison camp (Isla Quiriquina) in Chile”]

“In 2005, Ferrada de Noli opened a blog on human rights in Sweden, taking on the defence of WikiLeaks and the human rights cause of its founder Julian Assange.

A very long curriculum of a brave man, always at the forefront in the defence of human rights, thanks to publications and television interviews, even today, for European and American broadcasters. About a month ago, two publications, one in Germany and one in the Netherlands, included him among the “Top 25 Dissidents in the World in the Fight for Free Speech in 2025.”

Married, with seven children and 12 grandchildren, his family descends from the Genoese navigator Antonio de Noli (15th century), discoverer of the Cape Verde islands, and in Genoa he still has many cousins whom he visits often. To one of his ancestors, the canonical count Alessandro Noli,[4] who lived in 1800, is dedicated a street in Bergamo.

Marcello Ferrada de Noli has been in San Giovanni Bianco for about twenty years. In addition to being an academic and a protagonist in the defence of human rights, he is also an artist. He paints, and one of his paintings (depicting a family in which the father does not appear on the panel because he is imprisoned) has also been published by Amnesty International.

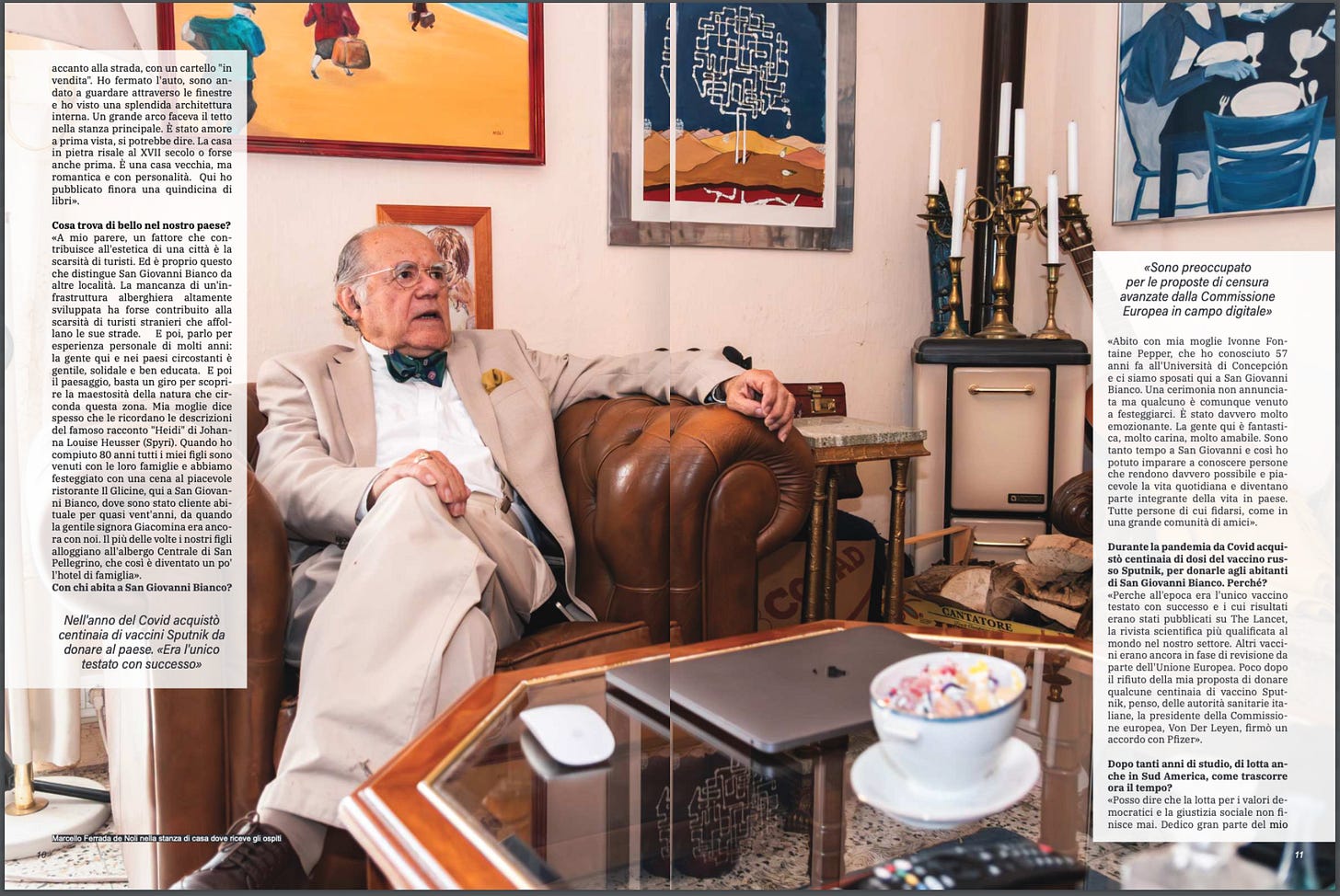

In San Giovanni Bianco lives in an old residence, with an arched dome-shaped interior ceiling, chandeliers on the table, furniture that is from the nineteenth century, some also brought from Sweden. On the walls there are photos, diplomas, distinctions from the Swedish academic world and Harvard.

“I like it that way,” he says, “it also reminds me of the family home in Chile.”

Outside his Jaguar with which he also travels to Sweden, crossing Europe to visit his children.

Why the Brembana Valley and why San Giovanni Bianco?

“There are practical reasons, but also aesthetic ones. As I neared retirement from my professorship in Gävle, Sweden, and at the Karolinska Institutet, I made several short trips to Italy to find a house in which to retire. Not to rest, but to find a place where he can continue to write, undisturbed, on those topics that are not academic. And also to take a break from interviews.

The Brembana Valley appealed to me because it is closer to Sweden than Liguria (Genoa) is, thanks to the airport (from Bergamo).”

“… And then because members of the old Noli family had also been active in Bergamo.”

“There are also aesthetic reasons. If someone respects its origins, the history of its people, they will undoubtedly appreciate an architecture that faithfully represents that era of the past. And that’s what I found in the village of Val Brembana. Its architecture, houses, buildings, are true representatives of those past centuries. Although they are nicely renovated and clean, they have remained intact in terms of style. These are not predominantly ultra-modern buildings like those found in metropolises.

Looking for ads on the internet, while I was in Sweden, I found some houses in Val Brembana. I flew several times to Bergamo and on each of those trips I had an appointment with an agency. On one of these visits, I went to see a house in Piazza Brembana. But I found it too problematic to renew it. On the way back to Bergamo, however, I saw an old house in San Giovanni Bianco, …” [text continues next page]

«… right next to the street, and with a sign “for sale”. I stopped the car, went to look inside the ground floor of the house through a window, and I have observed a splendid interior architecture. A large dome served as a ceiling in a main room on the ground floor. It was love at first sight, you could say. The house, built in stone, comes from the seventeenth century or perhaps the previous one. It is an old house, but romantic and with personality. Here I have published about fifteen books to date.” [4]

What do you find beautiful in our city?

“In my opinion, a factor that contributes to the aesthetics of a city is the absence of tourists. And this is what rightly distinguishes San Giovanni Bianco from other cities. The absence of a highly developed hotel infrastructure has perhaps contributed to the absence of foreign tourists wandering these streets.

And then – I speak from personal experience of many years – the people here and in the surrounding villages are very friendly, supportive and well educated.

And also, the landscape. A walk is enough to discover the majesty of the nature that surrounds this area. My wife often says that she is reminded of the descriptions of the famous story about “Heidi”, by Johanna Louise Heusser (Spyri).

When I turned 80, all my children came with their families, and we had a celebration at the cozy restaurant Il Glicine, here in San Giovanni Bianco, where I have been a regular customer for almost twenty years. From the time when the gentle Signora Giacomina was still with us. Most of the time our children stay at the Albergo Centrale hotel in San Pellegrino, which has become “the family hotel”.

Who do you live with in San Giovanni Bianco?

“I live with my wife Ivonne Fontaine Pepper, whom I met 57 years ago at the University of Concepción. We got married here in San Giovanni Bianco. It was an unannounced ceremony, but in any case, more than one spontaneously came to celebrate us. It was all very exciting. The people here are fantastic. Very loving, very kind.

I have lived so long in San Giovanni Bianco and so I have been able to learn to meet people who really make everyday life possible and enjoyable and become an integral part of life in the village. All people who can be trusted, as in a large community of friends.”

During the COVID pandemic, you acquired hundreds of doses of the Russian Sputnik vaccine, to donate them to the inhabitants of San Giovanni Bianco. Why?

“Because at that time it was the only vaccine whose tests had been successfully approved, and its results had been published in the medical journal The Lancet – the most qualified scientific publication in our sector. Other vaccines were still in the European Union approval phase. Shortly after the rejection of my proposal to donate a few hundred Sputnik vaccines, by, I think, Italian health authorities, the President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen signed an agreement with Pfizer.”

After so many years of study, of struggle even in Latin America, how does your time pass now?

“I can say that the struggle for democratic values and social justice never ends…” [text continues next page]

“I spend a lot of my time writing books and participating in the public debate on human rights and freedom of expression. I still publish The Indicter magazine, and it often happens that I am asked to participate in international television interviews on epidemiological and geopolitical issues.

In January 2014 I founded the publishing company Libertarian Books Europe. All this from my studio in the old and faithful house “with the gray walls and green shutters, a stone’s throw from the river”, in San Giovanni Bianco.

How is your activity of promoting and defending human rights and freedom of expression developed?

“First of all, my ‘activism’ is absolutely independent. I do not belong to any political organization in Sweden, Italy, Chile or anywhere else. I express my opinions exclusively:

(a) Through my articles published especially in The Indicter magazine, which is a Swedish online publication on human rights and geopolitics, of which I am editor-in-chief,

(b) On the Substack platform, registered in San Francisco, California, USA. It is a content and subscriptions platform for writers and publishers.

[Translator’s note: also, articles published in Researchgate.net, Consortium News, and Academia.edu].

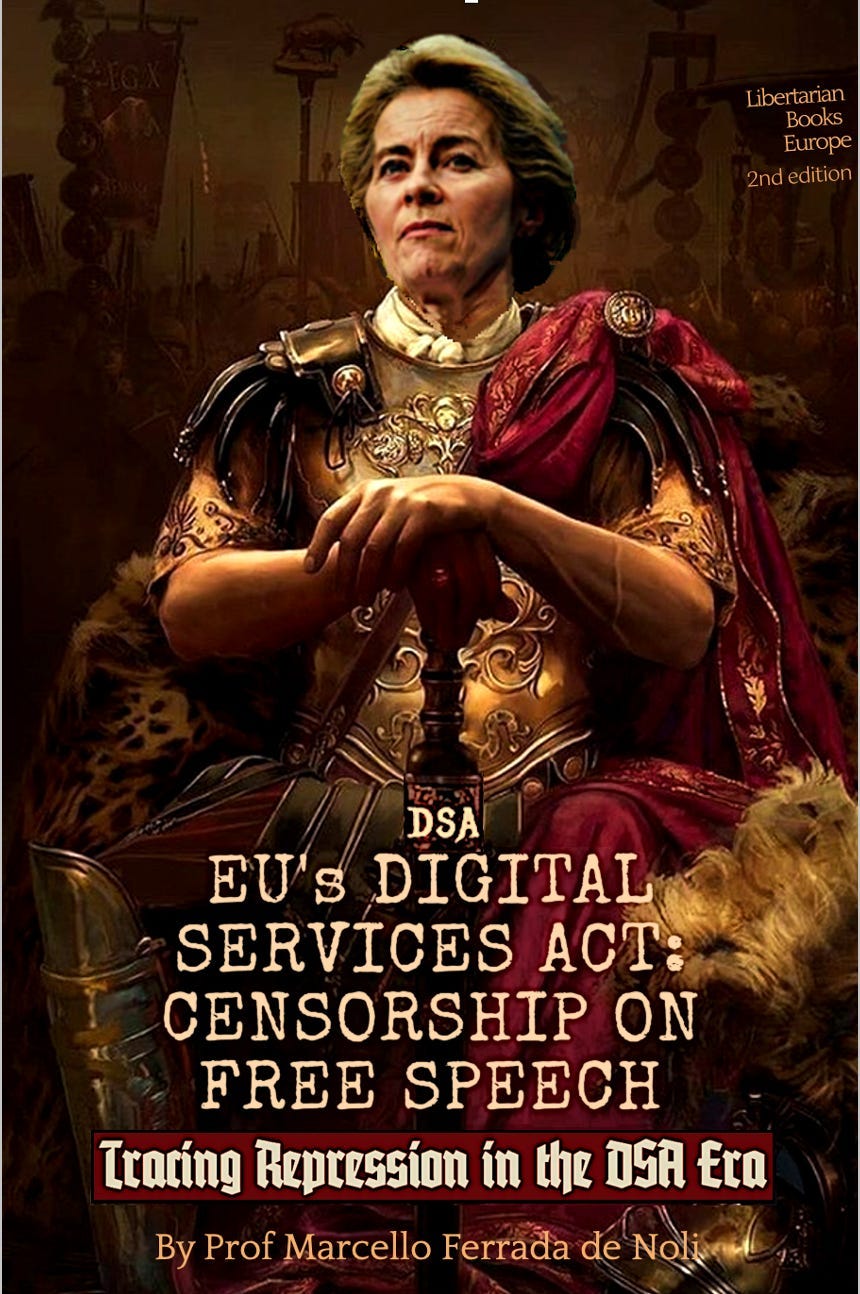

(c) Through my books which I publish primarily on Libertarian Books Europe. The books published by this publisher can be consulted and/or downloaded in their entirety.

(d) Finally, through interviews that I give to the media, including television channels.

However, I have never received any monetary compensation or payment in any form for any of these articles or interviews. The books and articles that I publish are free of charge and downloadable, in their entirety, by anyone”.

How do you judge freedom of expression in today’s Europe?

“I am particularly concerned about the new censorship proposal made by the European Commission, for the implementation of the already severe Digital Services Act (DSA).

The application of these regulations makes it possible to categorise as “hate speech“ even certain criticisms directed at the leadership of the European Union, either by some journalists or dissident authors.

And in my opinion, today, there is much to criticize in terms of the violation of democratic principles by governments and with respect to the constitutional rights of their citizens.

Recently, two publications, in Germany and the Netherlands, have included me among “25 of the world’s leading dissidents in the fight for freedom of expression in 2025”. And I can live with it. The list also includes Julian Assange, Edward Snowden and Roger Waters.

Then a dear friend from Bergamo told me, “You have to be careful, Marcello.” I replied, “They are the ones who need to be careful.”

After all, as Voltaire said, ‘it is always dangerous to be right in those things in which the holders of power are wrong.’”

Projects for the future in your home in San Giovanni Bianco?

“Here on the fourth floor of the house I have a small atelier where I paint from time to time, mainly portraits. Perhaps, promoting this activity could be a good project for the future. And then I would like to be able to mount an art exhibition here in San Giovanni Bianco or in Bergamo.”

A dear Swedish jewel parked in San Giovanni Bianco

Notes and references

[1] Val Brembana, in the Alpine sector of Lombardy, is a territory comprising 25% of the province of Bergamo (over one million inhabitants). This, together with the one in Milan, is considered the most prosperous in Italy. Val Brembana consists of a group of 29 cities or communes, most notable being San Pellegrino Terme, San Giovanni Bianco, Zogno, Piazza Brembana, and others. Its northern limit is very close to the border with Switzerland (Passo San Marco).Cities/towns of the Vallle Brembana: Algua; Averara; Blello; Bracca; Branzi; Brembilla; Camerata Cornello; Carona; Cassiglio; Cornalba; Costa Serina; Cusio; Dossena; Foppolo; Gerosa; Isola di Fondra; Lenna; Mezzoldo; Moio de’ Calvi; Olmo to Brembo; Oltre il Colle; Ornica; Piazza Brembana; Piazzatorre; Piazzolo; Roncobello; San Giovanni Bianco; San Pellegrino Terme; Saint Bridget; Sedrina; Serine; Taleggio; Ubiale Clanezzo; Valleve; Valnegra; Valtorta; Vedeseta; Zogno.

[2] “Across the terrorist-history of the Left Revolutionary Movement”) “A Través de la Historia Terrorista del Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionaria (MIR)”, El Mercurio, Santiago, August 25, 1973. Listed in the arresting order were as well Luciano Cruz, Miguel Enríquez, Bautista van Schouwen, and Andrés Pascal Allende.

[3] “Atacama“, a political alias used in the clandestine times of the 60’s, and with which he co-signed the first insurrectional thesis of the MIR in 1965 together with Viriato (Miguel Enríquez) and his brother Bravo (Marco Antonio)].

[3] He refers to the censorship of freedom of expression imposed by the “Digital Services Act of the European Union”, and which has been the subject of a recent book: “EU’s Censorship on Freedom of Speech – DSA Echoes of Fascist Repression in War Propaganda“.

[4] Referred to as the “Canonical Count Alessandro de Noli” in L’Eco di Bergamo, 20 January 2019.

[5] Published Books:

- 1962 Cantos de Rebelde Esperanza (Poetry) ISBN 978-91-88747-10-5

- 1967 No, no me digas señor (Play, on stage Teatro Concepción 1967). Scanned publication, 2015. ISBN 978-91-88747-16-7

- 1969 University and Superstructure (Philosophy) University of Concepcion, thesis

- 1972 Theory and Method of Conscientization (Social psychology)

- 1982 The Theory of Alienation and the Diathesis of Psychosomatic Pathology (Philosophy, psychiatry)

- 1993 Chalice of Love (Philosophy, fiction) ISBN 978-91-981615-9-5

- 1995 Psychiatric and Forensic Findings in Definite and Undetermined Suicides (Epidemiology, forensic psychiatry), Karolinska Institutet, Dept Clinical Neuroscience, Psychiatry Section, 1995.

- 1996 Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Immigrants to Sweden (Psychiatry), Karolinska Institutet, Dept Clinical Neuroscience, 1996. ISBN 91-628-1984-4

- 2003 Efter tortyr (Contributor author) (Torture, psychiatry), Centre for Survivors of Torture and Trauma (CTD), Stockholm. Liber, 1993. ISBN 91-634-0678-0

- 2005 Fighting Pinochet (Testimony, resistance). ISBN 978-91-88747-00-6

- 2007 Theses on the cultural premises of pseudoscience (Epistemology) ISBN 978-91-88747-05-1

- 2008 Kejsarens utbrända kläder (Epidemiology, psychiatry) ISBN 978-91-88747-01-3

- 2009 Oxford Textbook of Suicidology and Suicide Prevention, Oxford University Press, 1st ed., 2009. Print ISBN 9780198570059.( Contributor author) (Psychiatry)

- 2013 Da Noli a Capo Verde (Contributor author) (History) ISBN 978-88-8849-82-01

- 2013 Antonio de Noli And The Beginning Of The New World Discoveries (Editor)(Contributor author)(History) ISBN 978-91-981615-0-2

- 2014 Sweden VS. Assange. Human Rights Issues (Geopolitics, human rights) ISBN 978-91-981615-0-2

- 2018 Aurora Política by Bautista van Schouwen (Book chapter) ISBN 978-91-88747-11-2

- 2018 With Bautista van Schouwen (Political history) ISBN 978-91-88747-08-2

- 2019 Pablo de Rokha and the Young Generation of the MIR (Political History) ISBN 978-91-981615-5-7

- 2019 Sweden’s Geopolitical Case Against Assange 2010-2019 (Geopolitics, history, human rights) ISBN 978-91-88747-13-6

- 2020 Rebels With A Cause (Political History, Human Rights) ISBN 978-91-981615-2-6

- 2021 The Paradox of Life. Dialectical Reflections (Philosophy) ISBN 978-91-88747-10-5

- 2021 Those of us who founded the MIR (Political history) ISBN 978-91-88747-19-8

- 2021 Amore e Resistenza (Poetry) ISBN 978-91-88747-20-4

- 2021 Walter’s Wife and Other Stories (Fiction) ISBN 978-91-88747-02-0

- 2021 Kejsarens utbrända kläder (Epidemiology, psychiatry) ISBN 978-91-88747-01-3

- 2021 B flat of Combat (Poetry) ISBN 978-91-88747-33-4

- 2021 Esistenza Dialettica ISBN 978-91-88747-27-3

- 2021 My Fight Against Pinochet ISBN 978-91-88747-91-4

- 2023 When I Met Commander Che Guevara and his Thesis on Socialist Humanism (political theory) ISBN 978-91-88747-67-9

- 2024 Road to Malatesta (Philosophy, political history) ISBN 978-91-88747-39-6

- 2024 Back to Seventeen. Diary of Miguel Enríquez (Political history, biography) ISBN 978-91-88747-02-0

- 2025 Human Rights for All (Political history, human rights) ISBN 978-91-88747-30-3

- 2025 EU’s Censorship on Freedom of Speech – DSA Echoes of Fascist Repression in War Propaganda ISBN 978-91-88747-37-2

- 2025 Back to Seventeen. Diary of Miguel Enríquez. (Political history, biographical and historical commentary) ISBN 978-91-88747-18-1

-

2025 EU’s Digital Services Act: Censorship on Free Speech. Tracing Repression in the DSA Era. ISBN 978-91-88747-68-6.

You may also like

-

U.S. Interventions and Regime Repression in Latin America: The Political Epidemiology of Fatal and Non-Fatal Injuries, 1846–2026

-

From Guatemala to Venezuela: An Analytical Overview of U.S. Interventions in Latin America, 1954–2026. Political, Economic, and Human Consequences of an Era of Empire-led Interference

-

On DSA Censorship, Wokeism and Pseudo-Liberals

-

Should the EU’s DSA Ban Google from Silencing Gaza Genocide Voices? I Doubt It Shields Truth

-

An Essay on EU’s DSA Censorship on Freedom of Speech