In the context of new-elected far-right president José Antonio Kast, whose future government – if budget cuts and social austerity measures drives to extreme– may eventually encourage ideas of a new Social Outbreak (Estallido Social) amidst the Chilean poor.

By Marcello Ferrada de Noli, Professor Emeritus [*]

Abstract. This essay contends that a far-right government under the leadership of José Antonio Kast in Chile has the potential to create circumstances conducive to a new social outbreak. While the scale of such an event may parallel the 2019 Estallido Social, its form could differ. Rather than relying solely on sociological or economic frameworks, this analysis is rooted in a normative approach informed by political philosophy. The core of the article is the development of a theory of civil rebellion by the poor – the Objective Material Deprivation Theory. This thesis conceptualizes civil rebellion as a collective action that arises when systemic factors—structural inequality, political exclusion, and institutional rigidity—erode the legitimacy of the existing political order. It argues that, under specific conditions, civil rebellion represents a normatively meaningful response to persistent systemic injustice. Contemporary social discontent in Chile is thus analyzed not merely as protest or unrest, but as a potential expression of political agency in the face of systemic challenges.

C0NTENTS

-

- INTRODUCTION: The Far Right and Extreme Poverty as a Potential for Social Unrest in Chile – context, causes and perspectives

- Potential for Social Unrest

- The distribution of wealth in South American Countries

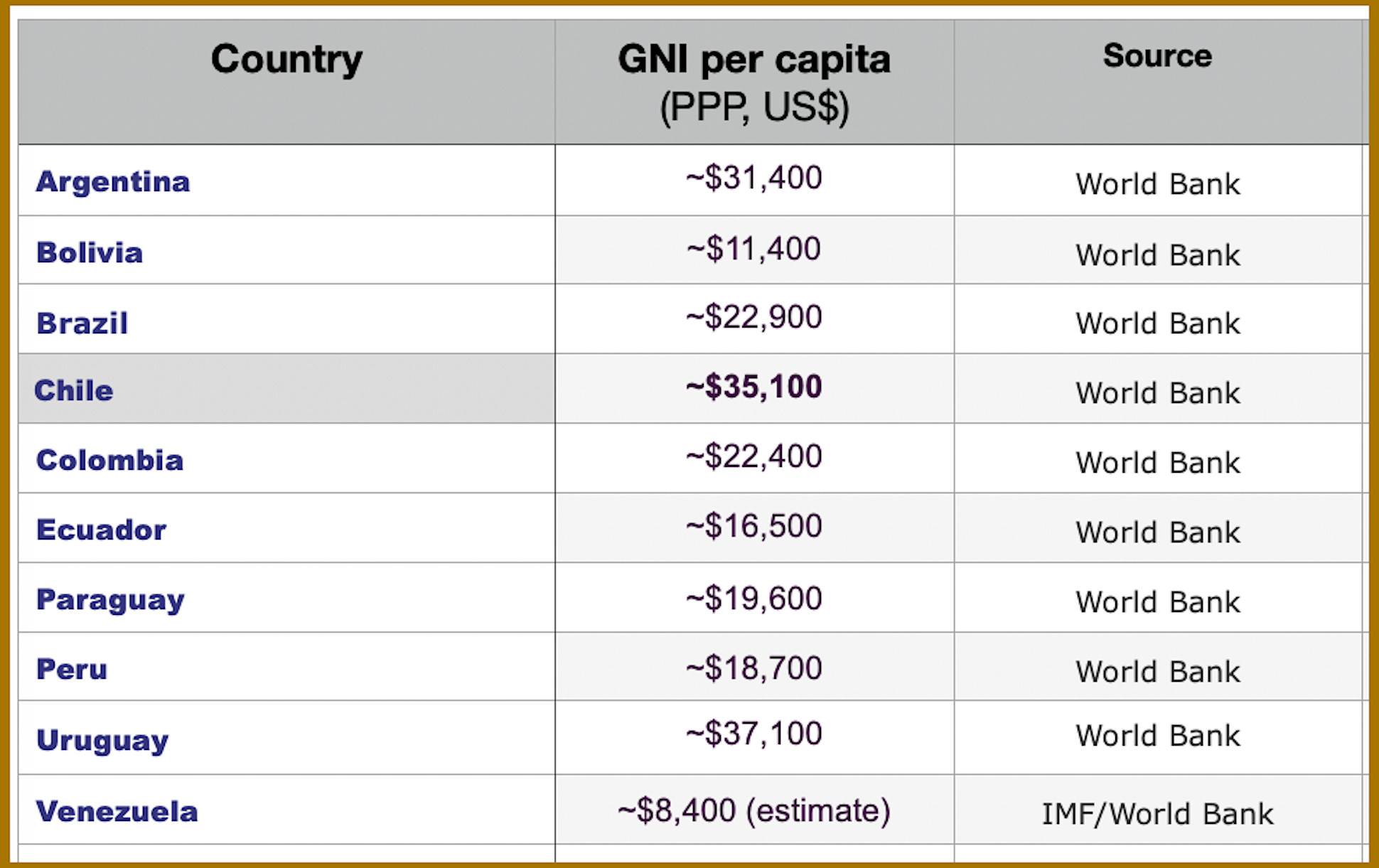

- Table 1: GNI Per Capita in the South American Countries

- Distribution of wealth in Chile

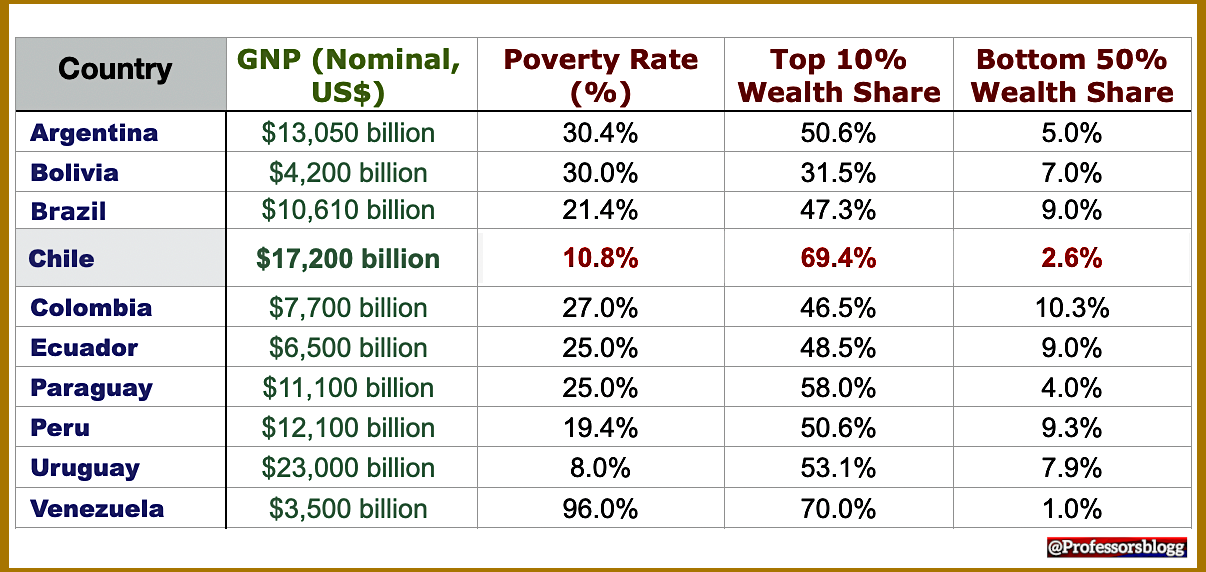

- Table 2: GNP, Poverty Rate and Wealth Share among the top 10% and Bottom 50 %.

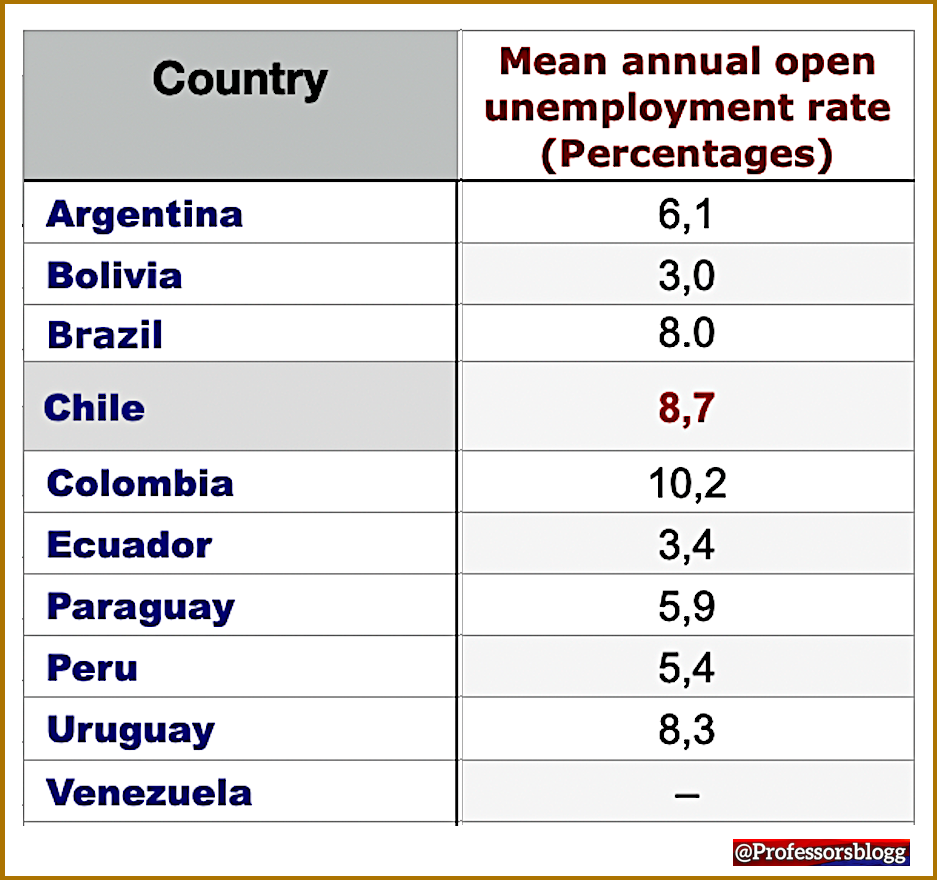

- Table 3. Mean Annual Unemployment Rate in Chile

- A theoretical model anticipating social unrest in response to rising poverty

- Objective Material Deprivation Theory

- Definitions 10

- Contesting Gurr’s Theory of Relative Deprivation

- The Direct Link Between Material Deprivation and Political Mobilization

- Social and Political Consequences

- Structural Factors and Motivations for Action

- Summary and Conclusion

- Popular Resistance in Chile

- Solidarity Protests of Students and Workers in Chile

- The 2019 Social Outbreak and its unfulfilled goals

- The Roots

- Death Toll, Injuries, and Victims of Violence During the Estallido Social

- Institutional Violence and State Accountability

- Legacy and Conclusion

- Ideology and Programmatic Issues Held by Antonio Kast as a possible catalysator for Social Outbreak

- José Antonio Kast

- Patria y Libertad

- Conclusion

- References and Notes

Introduction: The Far Right and Extreme Poverty as a Potential for Social Unrest in Chile – context, causes and perspectives

Chile, with a population of approximately 20 million, and Uruguay, home to around 3 million, are recognised as having the strongest economies in South America. Despite this economic strength, Chile faces notable challenges, including significant wealth inequality and a marked rise in extreme poverty. Recent research indicates that the proportion of Chileans living in extreme poverty has risen from 1.7 percent in 2015 to 2.1 percent in 2022 (CEPAL) [1].

Furthermore, wealth distribution remains highly skewed: the top 10 percent of Chileans hold 69.4 percent of the nation’s wealth, while the bottom 50 percent possess only 2.6 percent. While a 2022 WID report had previously established that Chile ranks highest (or lowest) in the world in terms of unfair wealth distribution. [Graphic below]:

In sum, Chile has the lowest share of wealth allocated to its poorest citizens among all South American nations, apart from Venezuela (WID.world). [2] The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) previously reported that only 1% of Chileans hold 26.5% of the nation’s wealth.

In March 2026, Chile will see the introduction of new neo-liberal policies under the leadership of the recently elected far-right president, José Antonio Kast. Kast is known for his admiration of the Augusto Pinochet military regime and for supporting the extension of Pinochet’s term of office in the pivotal 1988 referendum that ended the dictatorship. [3]

Potential for Social Unrest

Given this empirical backdrop, with data revealing a worsening socio-economic position for the most impoverished segments of society, this essay investigates the potential for a direct confrontation between these social realities and the incoming far-right government. The analysis suggests that Chile may be on the brink of social unrest even more intense than the upheaval experienced in 2019.

The entering government’s budget for social programmes signals cuts to welfare, housing, and pensions –while easing taxes for the rich. Proposed measures include reversing the ’40-hours legislation’ (implemented in 2023) [4] by increasing working hours, as well as raising the pension-eligible age from 65 to 75 for men and from 60 to 65 for women. These changes are likely to conflict sharply with recently social and labour reforms that benefited workers, low-income pensioners, and the unemployed.

History in Chile, as well as the logic underpinning confrontations between the populace and those in power, suggests that social unrest tends to provoke heightened state repression. Kast has already signalled his readiness to govern under state-of-emergency laws, which for many Chileans evokes memories of the country’s authoritarian past and raises concerns about the potential for further democratic backsliding.

This essay will explore several interrelated factors influencing this social and political constellation, which may predict the occurrence of a social outbreak:

- The precarious socio-economic conditions currently faced by the poorest segments of Chilean society,

- The outcomes and lessons from the 2019 social uprising (“el estallido social de 2019”).

- Analysis of the ideological and programmatic positions held by the newly elected Chilean president.

- Theoretical perspectives on political philosophy, focusing on both subjective and objective deprivation among the poor, and evaluating the capacity of a proposed Objective Material Deprivation Theory to explain potential social upheaval.

The distribution of wealth in South American Countries

Across Latin America, the wealthiest 10% of the population holds 57% of the economic resources, while the poorest 50% have access to only 8% of the total ––according to the World Inequalities Lab (WIL) of December 2025. [5] The table below shows the GNI per capita of Chike and otheres countries of South America.

Table 1: GNI Per Capita in the South American Countries [6]

Distribution of wealth in Chile

Despite its economic success (following only Uruguay at the top in the GNI per capita ranking, table above), Chile, on the other hand, exhibits a deplorable distribution of its wealth ––a wealth which is generated by the labour of all the Chilean workers.

Table 2 shows the distribution of wealth in the top ten percent of the rich, and at the bottom fifty percent. The table also shows the GNP.

Table 2: GNP, [7] Poverty Rate [8] and Wealth Share [9] among the top 10% and Bottom 50 %.

Even if, in general terms, poverty has decreased in Chile (13,2 in 2015 to 8,2 in 2022), extreme poverty has not. Instead, extreme poverty in Chile is higher (1,7 in 2015 to 2,1 in 2022). [10]

In sum, in Chile ––the second largest economy in South America in terms of GNP (Nominal, US$)– and despite having a very low poverty rate (second lowest), the top 10 percent share 69,4 % of the wealth, while the bottom fifty percent share only the 2,6 %. Being this the lowest share for the poor, after the Venezuelans’. And Chile’s mean annual unemployment rate is the second highest among South American nations:

Table 3. Mean Annual Unemployment Rate in Chile [11]

A theoretical model anticipating social unrest in response to rising poverty

Historically, a marked surge in poverty has consistently heightened the likelihood of violent protest and social resistance. In the context of Chile, where economic disparities are predicted to be further pronounced ––while austerity measures are expected to intensify hardship among the poor.

A general axiom would be that:

As poverty intensifies, the probability of mobilisation among working-class, student, and unemployed populations in response to perceived injustice increases.

However, in the case of Chile (and comparable societies), considered historically, the axiom may be stated more strongly:

An increase in poverty constitutes a sufficient condition for the political mobilisation of economically vulnerable groups against policies judged unjust.

The above is different to the theory of relative deprivation (Gurr, 1970),[12] which explains political violence, protest, and revolution, as arising from the perceived gap between what people think they deserve and what they actually have, or can obtain, rather than from absolute poverty. As in Gurr´s meaning of relative deprivation:

“Actors’ perception of discrepancy between their value expectations and their value capabilities.”

My proposition is different of that in Gurr’s theory. What I intend to conceptualise (as essentials beneath the causes and motivation for the workers’ protests which I am describing) has to do with real economic deprivation, rather with the notion that –in comparison with other classes– they should be entitled to more benefits from their society. It is not as much a “subjective perception”, but an “objective” existing misery which they must endure rather than “perceive”. I do separate relative/subjective deprivation from objective material deprivation.

Objective Material Deprivation Theory

My analysis is rooted in the belief that extreme poverty shapes motivations for collective action differently than relative deprivation, emphasizing the importance of objective material conditions over subjective perceptions.

In countries like Chile, where one percent has nearly a third of all wealth; where amidst the display of economic well-being and even luxurious fashions and goods displayed by the upper and middle classes, coexist an extreme poverty. Here in this space, the unprivileged have hardly the occassion to “perceive” a possibility to overcome their misery in the frame of the socio-economic and cultural system available to them. They might dream, but they might also act.

Particularly when the few social achievements they have receive by certain progressive legislations are taken away from them by far-right, discriminatory and anti-popular ideologies seizing state-power.

The motor of Resistance roars not in the subjective perception that others can enjoy better rights and nicer goods. It breathes instead in the existential whereabouts of their material misery.

Definitions

Objective Material Deprivation refers to the tangible and measurable lack of essential resources or necessities that individuals or groups experience. This encompasses, but is not limited to, factors such as income inequality, inadequate access to basic services like healthcare, education, and housing, ongoing food insecurity, and substandard living conditions.

In contrast to relative deprivation, which depends on personal perceptions or social comparisons, objective material deprivation is grounded in real and quantifiable hardships that individuals endure, irrespective of their expectations or how they compare themselves to others. While the concept of material deprivation has been widely discussed, I explicit focus on objective, measurable deprivation—separate from relative perceptions

While relative deprivation theories suggest that unrest emerges from feelings of deserving more or having less than others, objective material deprivation theory emphasizes the actual absence of fundamental needs.

Here, the issue is not what people “think” they lack, but what they concretely lack, such as safe housing, sufficient income, or access to education. For those living in extreme poverty, the driving force behind protest or political action is the lived experience of deprivation itself, not a comparison with others.

Contesting Gurr’s Theory of Relative Deprivation

As described above, Gurr’s Theory of Relative Deprivation (1970) is centred on the idea that political violence, protest, and revolution are driven by the perceived gap between what individuals or groups believe they deserve and what they actually possess or can obtain.

In this framework, the perception of deprivation—formed through expectations, social comparisons, or relative status—serves as the catalyst for unrest. Notably, this theory explains how groups that may be objectively better off than others can still feel disenfranchised and mobilize against perceived injustice. The key insight here is that relative deprivation is not solely the experience of those in absolute poverty; rather, inequality and unmet expectations can provoke collective action across socioeconomic strata.

In contrast, the Material Deprivation approach focuses on the direct experience of poverty and its role in political mobilization. This perspective asserts that for those living in extreme poverty, the issue extends beyond feelings of entitlement or expectations—it is rooted in the tangible hardships encountered daily.

For these individuals, “misery” is not a subjective feeling but a lived reality, and it becomes a clear trigger for action when their conditions are perceived as unjust. Political mobilization, in this framework, occurs primarily when there are actual increases in material deprivation, particularly among the most economically vulnerable. Unlike Gurr’s theory, this approach emphasizes objective poverty and the real deprivation suffered, such as lack of access to basic needs, as the direct impetus for collective action.

The fundamental difference between these frameworks lies in their focus: Gurr’s model centres on relative deprivation, highlighting how inequality or unmet expectations can incite unrest—even among those not experiencing absolute poverty.

Conversely, the Material Deprivation approach stresses the importance of actual, worsening material conditions as the driving force behind political mobilization. In this view, the objective reality of poverty, rather than relative frustration or comparison, is what compels groups to protest or rebel in response to perceived systemic injustice.

The Direct Link Between Material Deprivation and Political Mobilization

Objective material deprivation is presented as a sufficient condition for the political mobilization of economically vulnerable groups. When these groups encounter worsening material circumstances—such as deepening poverty or the erosion of social welfare—this directly fuels their motivation to challenge policies they perceive as unjust. For example, workers’ protests can be attributed to growing material hardships, like escalating costs of living, rising unemployment, and inadequate access to public services, rather than to mere perceptions of inequality.

Social and Political Consequences

a) Political Mobilization: Individuals in objectively deprived conditions, particularly among the working class, often lack adequate means to address their grievances through conventional avenues such as voting or negotiation. This limitation increases the likelihood of direct actions like protests, strikes, and revolutions. It was that kind of situation which triggered the 2019 Estallido Social in Chile. Impoverished people under progressive precarious material conditions did not find political channels for their demands. A commonly uttered criticism found in the literature referring the 2019 events mention the failure of the political establishment –traditional left parties included– to address the demands of a vast cohort of the Chilean people, pressed by their objective material conditions of existence. At the end, ontogenetic survival mechanisms constantly prevail and make themselves heard in the socio-political space.

b) Resistance and Revolution: When materially deprived groups perceive that their conditions are being ignored or exacerbated by government policies, they may resort to more extreme forms of political violence or organized rebellion, viewing such actions as necessary means to demand change.

Structural Factors and Motivations for Action

a) Institutional Failures: The Objective Material Deprivation Theory highlights the role of state structures that fail to meet basic needs or perpetuate systemic inequality. Policies that favour the elite or overlook the welfare of vulnerable populations serve as catalysts for mobilization, and

b) Economic Inequality: Rather than concentrating on perceived inequality, the theory underscores actual disparities in economic access, opportunity, and wealth distribution.

Unlike theories that rely on the gap between expectation and reality, Objective Material Deprivation Theory posits that the real conditions of poverty and deprivation themselves are sufficient motivators for action. There is no need for complex psychological processes or subjective interpretations—individuals engage in collective action because they are experiencing real hardships that threaten their basic survival or dignity.

Summary and Conclusion

i) Real material deprivation—such as poverty and lack of basic services—is identified as the primary force driving political mobilization among economically vulnerable groups.

ii) Objective hardship is distinguished from subjective perceptions and can be measured through concrete indicators like income, housing conditions, and access to healthcare.

iii) Increasing material deprivation within individuals or communities can spark collective action or protest unjust policies, without requiring a sense of relative unfairness or comparison.

iv) Political mobilization emerges as a natural response to worsening material conditions, and affected groups may resort to protest or even violence as a consequence of these hardships.

v) Material Deprivation as Objective: Emphasizes that deprivation is a real condition faced by individuals, not merely a psychological experience.

vi) Political Mobilization as a Response: Asserts that this deprivation is both the trigger for and a sufficient condition for political action.

vii) Distinction from Relative Deprivation: Stresses that the theory is concerned with objective conditions, not subjective comparisons with others.

Popular Resistance in Chile

Photo TheClinic.cl

Concretely, in Chile, political activism has often arisen in response to specific governmental measures that disproportionately affect the most vulnerable sectors of society. Notably, increases in transportation fares have served as catalysts for widespread demonstrations, as seen in April 1957 and more recently in October 2019. These actions have typically been met with violent repression from governmental forces, highlighting the deep-seated tensions between the state’s policies and the population’s demands for greater equity.

Solidarity Protests of Students and Workers in Chile

Diario Concepción, 4 November 2024. Photo: Isidoro Valenzuela M.

The poorest members of society, together with students, have played a central role in these protest movements. As first-hand experience offers insight into the nature of these movements, I may refer that, as head of the MIR university brigade (Brigada universitaria del MIR en la Universidad de Concepción) during periods in the 60’s, together with a mass of fellow students I participated in various significant episodes of social unrest that were marked by direct confrontation between protesters and police forces.

One noted episode was the violent clashes with police forces during the national strike of the Health Workers Union in 1967 ––where many of us resulted arrested. Another example is the violent protests by the street market workers in La Vega in Concepción at the end of the 60’s, which we also joined. This was a particular violent encounter, where police forces, equipped with automatic weapons intended to launch tear gas projectiles at a distance, [13] instead fired them at close range, directly into the crowd of workers and students carrying out the protest –-resulting in seriously wounded protesters. [14]

In sum, these events illustrate the central role played by society’s most vulnerable groups alongside students. Their actions, often at considerable personal risk, has been pivotal in shaping the character and outcomes of these protest movements in Chile in advancing social demands, reflecting the deep social divisions and shared grievances among those most affected by inequality and economic hardship. Another “constant” factor in these processes is represented by the involvement of vast police forces, or eventually, the military, which has invariably resulted in an escalation from the part of the protesters and vice versa.

The 2019 Social Outbreak and its unfulfilled goals

Watch video by the author at The Indicter Channel [18]

During the period of social unrest known as the 2019 Estallido Social, an outbreak which lasted from October 2019 to March 2020, there were significant reports of deaths, injuries, and acts of violence affecting both protesters and, to a minor extent, law enforcement personnel.

According to Human Rights Watch, in just one month (from October 18 to November 20, 2019) almost 11,000 individuals were injured, including 2,000 police officers, and 26 people lost their lives. Over 15,000 were detained, with some reportedly subjected to ill-treatment. Several suffered eye injuries—most from pellets fired by police using anti-riot shotguns. [15]

The Roots

The estallido social in Chile, while immediately triggered by an increase in public transport fares, swiftly revealed a series of deeper, long-standing issues that had been simmering within Chilean society. The outbreak thus became a catalyst for widespread public frustration, reflecting the population’s ongoing struggles and dissatisfaction. It is popularly referred [16] that the outbreak was caused by:

- High cost of living in Santiago,

- Inadequate pension systems,

- Expensive healthcare and the high prices of essential drugs,

- Distrust in political leaders and institutions, widespread lack of trust in the political class,

- Calls for constitutional reform, as the country’s constitution was regarded as outdated and no longer representative of modern societal needs.

But The 2019 Chilean “Estallido Social” was sparked by a multitude of socioeconomic, political, and cultural factors, beyond the issues mentioned above. These factors converged to fuel widespread discontent and ultimately led to mass protests that began in October 2019. Here below a breakdown of the information above:

High Cost of Living in Santiago –– One of the most significant factors fuelling public unrest was the high cost of living, particularly in Santiago. As one of the most expensive cities in Latin America, many residents found it increasingly difficult to afford basic necessities, intensifying everyday financial pressures and contributing to a growing sense of social inequality. [17]

Inadequate Pension Systems –– Another major source of discontent stemmed from the inadequacy of pension systems. Many Chileans, especially retirees, faced low pensions that failed to provide a sustainable or dignified standard of living after years of work. This issue left a significant portion of the population feeling vulnerable and unsupported.

Expensive Healthcare –– The high prices of essential drugs and healthcare treatments added further strain on families across the country. The difficulty in accessing affordable healthcare highlighted broader social injustices and deepened public dissatisfaction with existing systems.

Distrust in Political Leaders and Institutions ––Alongside economic concerns, there was a widespread lack of trust in the political class. Years of accumulated institutional discredit led to a pervasive rejection of political leaders and government institutions, intensifying demands for meaningful change and accountability.

Calls for Constitutional Reform –– Finally, many citizens regarded the country’s Constitution as outdated and no longer representative of modern societal needs. This perspective strengthened calls for comprehensive reform and social transformation, as people sought a new framework that better reflected contemporary values and aspirations.

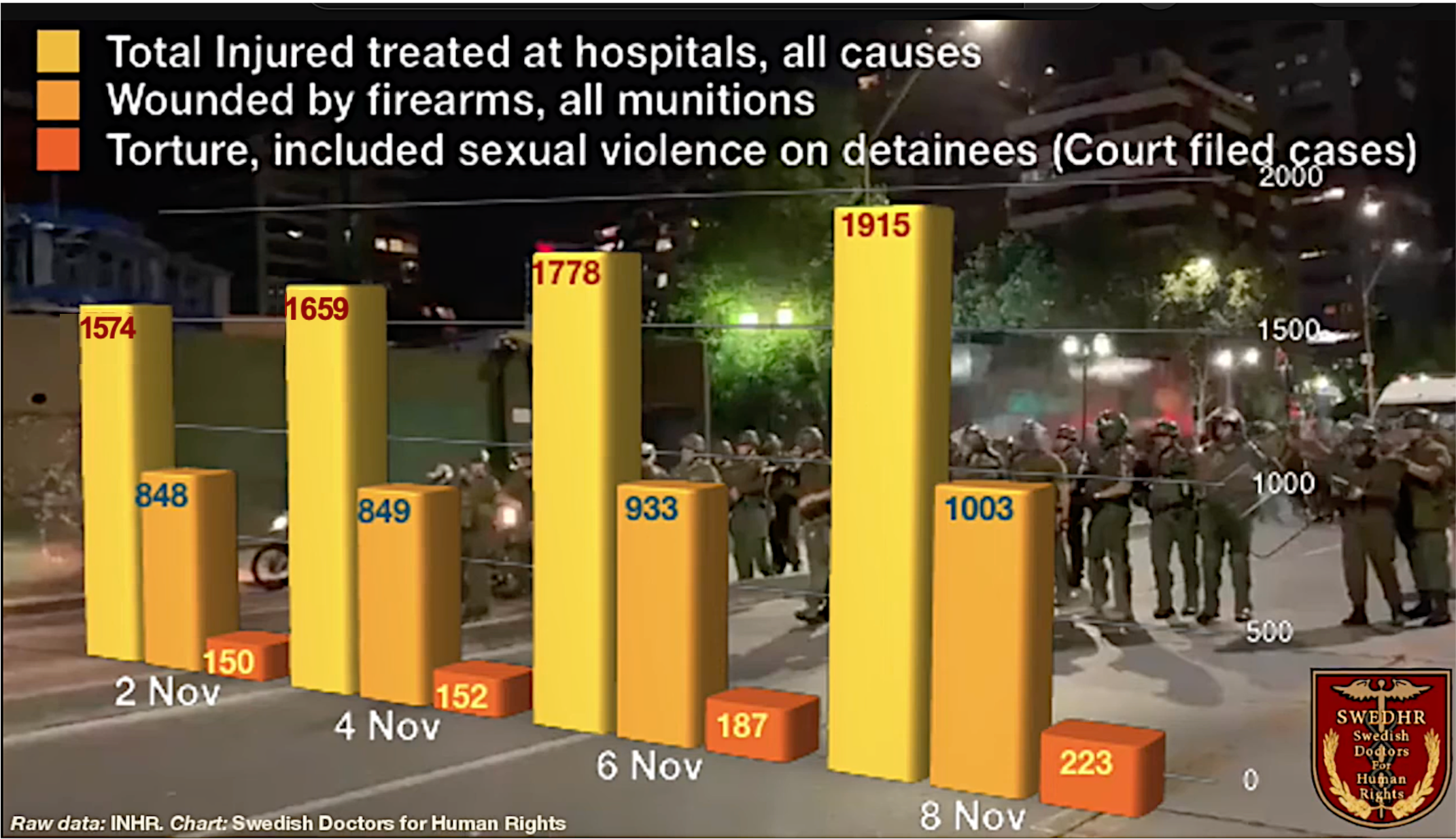

Death Toll, Injuries, and Victims of Violence During the Estallido Social

The Public Prosecutor’s Office officially recorded 30 deaths associated with the unrest between October 2019 and March 2020. [19] However, other sources have cited figures ranging from 31 to 36 deaths related to the events that occurred during those months. [20]

Various accounts indicate that hundreds or even thousands of protesters sustained injuries during the clashes that took place. Injuries among the forces exercising governmental repression (police officers and others) were considerably less. Among most serious injuries were those documented by judicial and human rights reports, which highlighted thousands of individuals who suffered physical harm.

Above: graphic by Swedish Doctors for Human Rights. See video

Notably, there were 464 documented cases of eye trauma, with many victims sustaining severe eye injuries from pellets. [21]

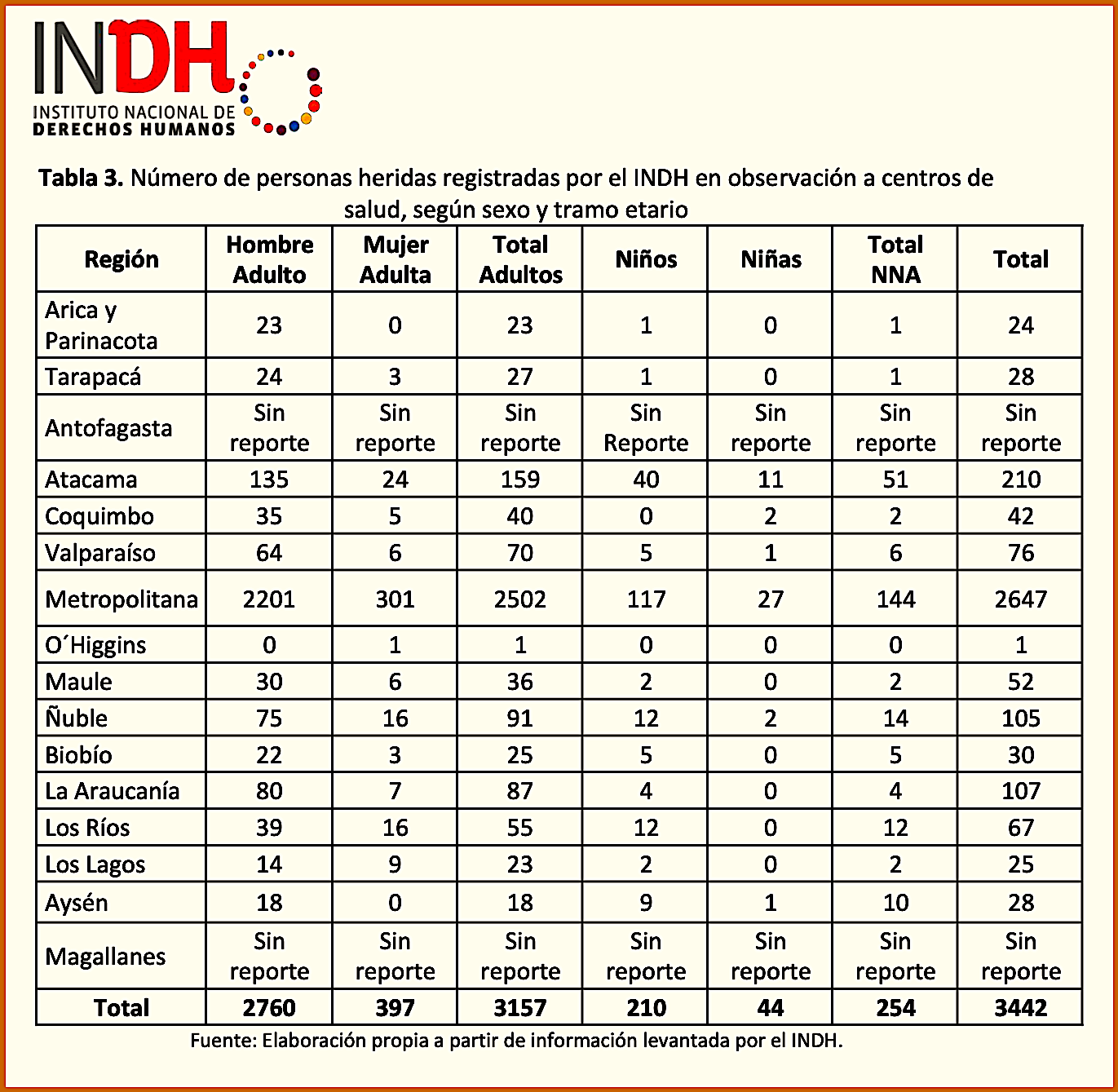

In a comprehensive four-year assessment, the National Institute for Human Rights (INDH) reported that 3,581 individuals experienced physical injuries as a result of the unrest. The INDH also registered thousands of legal actions concerning human rights violations, including instances of unlawful coercion, torture, and unnecessary violence. According to the INDH, 3400 civilians were hospitalized between October 17 – December 6, following the protest repression.[22]

Of the 4,994 complaints received and validated, 1,365 were filed nationwide regarding arbitrary detentions in the INDH’s electronic system. The Metropolitan Region had the highest number of these complaints with 673, followed by Valparaíso with 214 and Biobío with 111.

Table above published by Instituto Nacional de Derechos Humanos (INDH)[23]

The Carabineros (Chilean National Police) received the most complaints for this type of detention, with 1,164, of which 489 occurred during the state of emergency. Regarding home invasions and illegal searches, the INDH received 104 complaints between October 18 and November 30. However, as of the closing date of this preliminary report, the INDH does not have disaggregated data on how many of these procedures were carried out with the required court orders and in which cases there was an unlawful use of force.

Graphic above published by Instituto Nacional de Derechos Humanos (INDH)[24]

Out of 4,994 validated complaints, 1,365 nationwide concerned arbitrary detentions recorded in the INDH system. The Metropolitan Region reported the most (673), with Valparaíso at 214 and Biobío at 111. Carabineros received 1,164 complaints for such detentions, including 489 during the state of emergency. From October 18 to November 30, INDH recorded 104 complaints about home invasions and illegal searches, but as of this preliminary report, lacks detailed data on court orders or use of unlawful force in these cases. (Data from INDH).[25]

Institutional Violence and State Accountability

Among the various types of crimes reported during the Estallido Social, institutional violence committed by state agents was particularly prevalent. This form of violence constituted 34.1% of all recorded crimes throughout the period, making it the most common category of offence. In total, 11,506 cases and 12,002 related offences were documented under this category. [26] The majority of these incidents involved unlawful coercion and abuses directed at individuals, highlighting a significant pattern of misconduct and human rights violations perpetrated by authorities during the unrest.

Legacy and Conclusion

In my opinion, the political legacy of the social uprising of 2019 consists not in the political and social reforms that the protest movement could achieve. At the contrary, its legacy represents more the frustration among the million who protested ––and that of the millions they represented– when they perceived that their blood spilled did not led neither to the change of the constitution or the reforms they so vehemently struggled for.

On the other hand, the frustration following the unfulfillment of the protesters’ demands, would remain in their sentiments –which, psychologically considered, may serve for good or worse as a potent catalysator impelling a resumption of their struggle in case it will occur.

Such violent confrontations are not desirable by anyone, and what politicians and community organizations should do, is to explore all possible mechanisms of dialogue, democratic-wise issued of legislations at national level, and at regional and local level, to ensure that the voice of the poor is heard –and their needs met.

The Estallido Social in Chile was the result of a complex interplay of economic, social, and historical factors that ultimately erupted into widespread protests in 2019. The movement was not triggered by a single event, but rather by a convergence of longstanding grievances and structural issues within Chilean society.

Economic inequality remains a major issue in Chile, where the neoliberal model, implemented in the late twentieth century, led to uneven wealth distribution, limited access to education, and reduced social mobility, causing widespread frustration and resentment among large segments of the population, particularly the less favoured and which ––considering the cuts in social programs announced by the upcoming Kast government– shall experience further objective material deprivation.

Beyond economic factors, social injustices played a critical role in the unrest. Issues such as social exclusion, regional disparities, and the marginalization of certain groups intensified feelings of discontent. Many Chileans experienced barriers to accessing basic services and opportunities, deepening the divide between different regions and communities.

The legacy of authoritarianism in Chile continues to influence the nation’s political and social landscape. Historical grievances stemming from past regimes have left lasting scars, with segments of the population feeling that justice and reconciliation remain unfulfilled. These unresolved issues contributed and will continue to contribute to the widespread calls for change.

In addition to the factors above, growing demands for political reforms became increasingly prominent. Many citizens viewed Chile’s political system as outdated and unresponsive to the needs of modern society. Calls for greater representation, transparency, and accountability echoed across the country. The call for a new Constitution, whose approval ultimately failed, has left not only unresolved issues, but because those same unsettled matters, after six-seven years, have worsened amidst the reality of the socially disadvantaged. A heightening on those concerns paves the risk of new direct confrontations.

The struggle for indigenous rights and the fight against gender inequality also became central themes within the Estallido Social. Indigenous communities sought recognition and respect for their rights and identities, while movements for gender equality highlighted persistent disparities and demanded systemic change.

Each of these factors is deeply interconnected, and their combined effect created an explosive situation that led to the 2019 Chilean social unrest. The Estallido Social stands as a testament to the power of collective action in the face of enduring inequalities and the ongoing pursuit of justice and reform in Chilean society.

Ideology and Programmatic Issues Held by Antonio Kast as a possible catalysator for Social Outbreak

José Antonio Kast

International media coverage of Chile’s new president, José Antonio Kast, has been largely consistent. Kast is described as the son of a German immigrant who served as both a Nazi party member and an army lieutenant. Kast has stated that his father was conscripted into the Nazi party against his will. Following World War II, his father fled to South America, eventually settling in Paine, south of Santiago. [27]

It is added that Kast’s eldest brother, Miguel Kast, played a significant role in Chilean government during the early 1980s. He served as a government minister and as president of the central bank under the dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet. During this period, over 40,000 individuals were executed, detained, disappeared, or tortured. Miguel Kast was one of the “Chicago Boys,” economists who implemented shock-therapy policies characterized by deregulation and privatization. [28]

According to La Tercera (English edition), In 1984, José Antonio Kast commenced his studies in Law at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile (PUC). This period marked not only the beginning of his formal education in the legal field ––which would serve him as a future legislator as member of the Cámara de Diputados (the Chilean Congress), [29] but it also pivoted his ideological path into neofascist positions such as fervent anticommunism, economic neo-liberalism and praise of authoritarian rule (e.g. his repeated admiration of Pinochet’s dictatorship).

This transition was marked by his association with Jaime Guzmán (the right-wing politician and Pinochet’s chief adviser, who had a principal role in the “Pinochet Constitution”), to whom Kast met at the PUC.

Photo published in La Tercera, 12 December 2025 [30]

Many Opus Dei members at PUC have influenced the university’s academic and ideological direction through faculty and leadership roles. Although PUC is not governed by Opus Dei (neither there is any evidence that Kast would be member of Opus Dei), its Catholic background and ties with conservative intellectuals have boosted this influence, particularly in institutional ideology.

Opus Dei’s anti-communist stance, rooted in Catholic doctrine, has shaped its presence in education and public life, especially regarding socialism and left ideologies.

José Antonio Kast ideological positions can be summarized in three pillars: catholic-conservatism, profound anticommunism, praise of authoritarian government, economic neo-liberalism, and ethnocentrism.

One year after commencing his university education at PUC, and at the times of his association with Guzmán, Kast entered the Movimiento Gremial (Gremial Movement):

The Movimiento Gremial (Gremial Movement) was founded by Jaime Guzmán—who played a significant role as an advisor to the regime and was the principal architect of Chile’s present Constitution—this movement held considerable influence during a period when the nation’s political discourse was largely shaped by Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship.

In political right-wing contexts, “Gremialism” is also associated with fascism.

Patria y Libertad

Another issue is represented by the alleged association of José Antonio Kast and the founder of the neofascist Movimiento Patria y Libertad.

Patria y Libertad participated in violent actions during Pinochet’s early regime, targeting leftists, opposition groups, trade unions, and students, and “was responsible for several assassinations and attacks on those labelled as Marxist or left-wing sympathizers.” [31]

Rodríguez Grez described Kast as the leading figure of right-wing values rooted in Patria y Libertad and similar Chilean movements. He believed Kast can restore order to a country he views as overly left-leaning and supports Kast’s positions on social conservatism, opposing abortion rights, LGBTQ+ rights, and advocating traditional family values. [32]

Symbolism of the Partido Republicano’s Logo

Photos above: La Izquierda Diario [33]

The Republican Party of Chile, founded by José Antonio Kast in 2019, is a far-right party formed as an alternative to traditional right-wing groups, especially the more moderate Chile Vamos coalition (including UDI –– the Independent Democratic Union).

“While Kast is seen as the key figure behind the party, his political roots are intertwined with the authoritarian legacy of the Pinochet dictatorship and with more radical right-wing groups like Patria y Libertad.” [34]

It is worth noting that the official logo adopted by José Antonio Kast for the Partido Republicano de Chile which he founded, closely resembles the emblem used by the Alianza Nacional.

The Alianza Nacional was chaired by Álvaro Corbalán, a former CNI agent, and who is currently serving a sentence exceeding 100 years at Punta Peuco for crimes against humanity. [35] In the photo above at right, Dictator Augusto Pinochet himself delivered the inaugural speech of the said party.

This symbolic choice of the logo for the party founded by the now elected president of Chile, draws a direct visual and historical connection to the Alianza Nacional and highlights the ideological continuity with the military dictatorship embraced by Kast’s political movement.

Conclusion

“The greatest rebellion

is the one that is forged in

the silence of the oppressed.”

– Audre Lorde (1934–1992)

[In progress]

References and Notes

[1] Formerly at the Social Medicine Section, Dept of Public Health Sciences, Karolinka Institute (Sweden), and Dept of Social Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston (USA). Profesor de Filosofía, formerly Professor of Psychosocial Methods at Concepción University (Chile).

[1] CEPAL, Panorama Social de América Latina y el Caribe 2025. “Cuadro I.A1.3 América Latina (16 países): indicadores de pobreza extrema y pobreza, 2014-2024”. Page 75.

[2] Wealth shares based on World Inequality Database (WID.world), latest available estimates.

[3] Pierre Haski, “Pinochet’s Shadow And Chile’s Choice Of José Antonio Kast“: “He is the first Chilean president to have voted in favour of extending Pinochet’s term of office in 1988, during the famous referendum that ended the dictatorship.” WorldCrunch, 15 December 2025.

[4] “Ley de Cuarenta Horas”, ley 21.571. Approved in Congress April 11, 2023. It came into effect April 26, 2023.

[5] “Latinoamérica es la región más desigual por ingresos y también de las que más en riqueza“. Swiss.info, 10 December 2025.

[6] GNI per capita (PPP) accounts for variations in price levels between countries, providing a more accurate representation of the residents’ relative purchasing power.

[7] Estimates based on World Bank data and IMF projections (nominal GNI per capita, current US$).

[8] Poverty rate based on World Bank estimates using national household survey data (CASEN).

[9] World Inequality Database (WID.world), latest available estimates.

[10] CEPAL, Panorama Social de América Latina y el Caribe 2025. Op. cit.

[11] CEPAL, Statistical Yearbook for Latin America and the Caribbean (2024). Page 20.

[12] Gurr, Ted Robert (1970). Why Men Rebel. Princeton University Press.

[13] The weapon appeared similar to the M60 of the sixties.

[14] A seriously injured student a cause of the close-range fired canisters was named Felipe Ramírez. He received the direct impact of a tear gas canister on the upper part of his forehead, losing brain mass (information provided by Dr. Renato Valdés Olmos, 18 December 2025). “A seriously injured student a cause of a close-range fired canister was named Felipe Ramírez. He received the direct impact of a tear gas canister on the upper part of his forehead, losing brain mass [information provided by Dr. Renato Valdés Olmos (18 December 2025). Dr. Valdés Olmos was then a medical student at the University of Concepción, who also participated in the referred La Vega protests of 1968 and was close to Ramirez when the impact that injured him occurred. He collaborated in the transport of the injured victim for emergency treatment at the Concepcion Regional Hospital.

[15] “Chile. Events of 2020“. Human Rights Watch. World Reports 2021 – Essays.

[16] Spanish Wikipedia, “Estallido Social”. Assessed 17 December 2015.

[17] “Santiago se mantiene como la segunda ciudad más cara de Latinoamérica“. Cooperativa.cl, 26 June 2019.

[18] Video: “Chile – Violenta Violenta Repression Continúa“. The Indicter Channel, YouTube, 2019. Assessed 15 December 2025.

[19] Francisco Rosales, “A seis años del estallido social: Fiscalía Nacional reporta más de 35 mil delitos, 30 muertos y 464 víctimas de trauma ocular“. El Dínamo, 18 October 2025.

[20] “Estallido Social“. (Spanish) Wikipedia. Accessed 17 December 2025.

[21] Francisco Rosales, “A seis años del estallido social: Fiscalía Nacional reporta más de 35 mil delitos, 30 muertos y 464 víctimas de trauma ocular“. Op.cit.

[22] @INDH, 6 de diciembre de 2019

[23] “Informe Anual Situación de los Derechos Humanos en Chile 2019“. Instituto Nacional de Derechos Humanos (INDH). No date of publication.

[24] “Informe Anual Situación de los Derechos Humanos en Chile 2019“. Instituto Nacional de Derechos Humanos (INDH). No date of publication.

[25] Ibidem., Page 81.

[26] Francisco Rosales, “A seis años del estallido social: Fiscalía Nacional reporta más de 35 mil delitos, 30 muertos y 464 víctimas de trauma ocular“. Op.cit.

[27] Fabian Cambero , Sarah Morland and Rosalba O’Brien (Reuters), ” Chile’s next president traces politics back to Pinochet era“. USA Today, 15 December 2025.

[28] Ibidem.

[29] Nicole Iporre, “Who is Jose Antonio Kast, the new President of Chile?“. La Tercera, 14 December 2025.

[30] Ibidem.

[31] ChatGPT, “Patria y Libertad (PyL) Overview”: Accessed 19 December 2025. Screenshot available by the author.

[32] ChatGPT: “Rodríguez Grez has described Kast as the best representative of the right-wing values that have defined Patria y Libertad and other ultra-right movements in Chile. For him, Kast is the leader who can restore order to a Chile he believes has become too left-wing. Rodríguez Grez supports Kast’s views on social conservatism, including his opposition to abortion rights, LGBTQ+ rights, and his stance on traditional family values.” Accessed 19 December 2025. Screenshot available by the author.

[33] “La “coincidencia” simbólica del Partido de Kast y del partido de la CNI Avanzada Nacional“. LaIzquierdadiario.com, 11 June 2019

[34] Ibidem.

[35] ChatGPT. Op. cit.

The Apparent Contradictions

Although I was unable to vote, I was in Chile during the last weeks of the presidential campaign. I could follow two of the presidential-campaign debates and interact with voters of diverse preferences.

One issue to observe was the changes in the program of Kast´s campaign in reference to social and labour reforms.

Regarding the 40 hours week-labour

(fue desautorizado por Carter y el hueñe)

Why a violent confrontation?

Partly because it was announced by Kast as well his mayor ally Kaiser (search)

The rurstation with tpoliticias includinfg Boris (e, ISAPre , heath reform, etc)

XXX

You may also like

-

“The ‘good retirement’ of the combat doctor” – Interview in Italy to Professor Marcello Ferrada de Noli

-

EU’s censorship on freedom of speech overrides democracy, ignores UN Chart on Human Rights for All

-

Part 4. SWEDHR analyses on the Khan Shaykhun and Sarmin allegations by the White Helmets were correct and verifiable. Debunking Kragh’s & Shyrokykh’s disinformation

-

Global Assange Amnesty Network (GAAN) call upon Amnesty International to declare Julian Assange a Prisoner of Conscience retroactively

-

“The European Union leadership is a club of losers”