A look at the Telegraph’s recent photograph.

Oped by Eva Roberts.

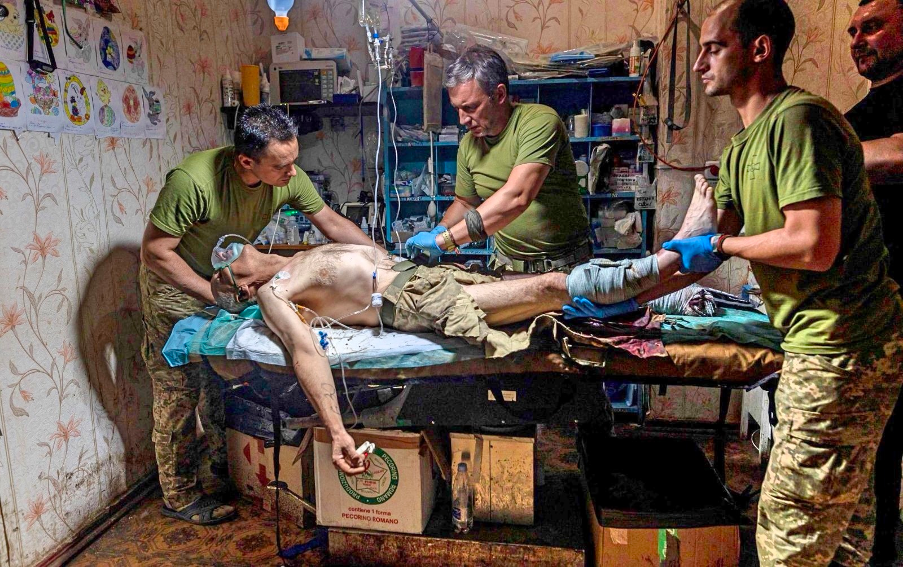

On 28th July Telegraph readership was presented with a photograph, captioned “Ukrainian army medics treat wounded soldiers at a stabilisation point in the direction of Bakhmut. CREDIT: Anadolu Agency/Anadolu” It is surely a study in Western media’s portrayal of Ukrainians.

The original version as appeared in the Telegraph, here below:

It may be that the picture above was taken in such poor light conditions (which might be doubtful, considering that surgical intervention is going under procedure). However, adding a commonly used “enhance” filter with help of a photo editor, the result will be:

And same original picture with light added:

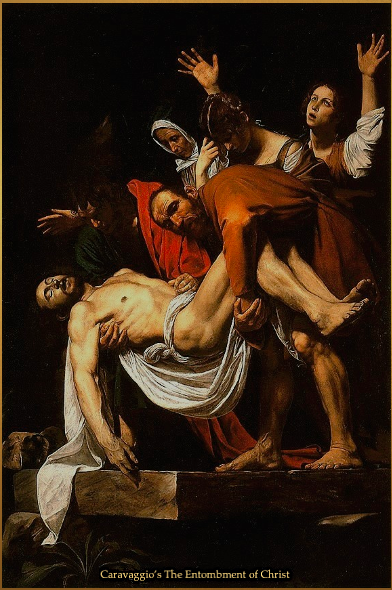

Caravaggio’s The Entombment of Christ:

The impression made by the picture relies heavily on the impact of light and dark. If you add light, you can clearly see there are five, not four people in the picture. The fifth man, in a black top with a black beard, is otherwise almost lost in the darkness. Add light and you will see him standing at the foot of the table/bed, behind the medic holding the wounded soldier’s leg.

You can also see more clearly that the wounded soldier could be an older man, he has receded white hair and the skin around his jaw looks wrinkled. One could think he is in his sixties or older.

In the Telegraph picture as it is, it is possible, if we look hard enough, to see there is a foot missing at the end of the soldier’s leg. Adding light to the picture it is possible to see the blood stains on the trouser leg beneath him, cut open to expose his leg.

As well as concealing the fifth man and somewhat the age of the soldier, the dark also hides the dirt and the grime, the items that clutter the shelves behind the medics, and the details on the walls.

Darkness was used in Renaissance art by painters such as Caravaggio, whose powerful contrasts between light and dark created dramatic illumination. Darkness itself can be a powerful feature of an image. Returning to the Telegraph picture, we can see that if we remove the darkness, we can entirely identify each item in the room, darkness itself being a powerful feature of the published picture. The terms tenebrism and chiaroscuro come to mind – showing black areas for the purpose of contrast and effect, or incorporating small sections of shadow to direct the onlooker’s eye. But there’s more to it than dramatic effect and imagination. Now we turn to the question of light.

The main purpose of light is to draw the eye to the picture’s focal point, a classic technique to spotlight. We see this again in Caravaggio’s art. In his painting “The Entombment of Christ”, exhibited in the Vatican Museum, Christ’s body is being carried by two men, Nicodemus and the apostle John. The crucified Jesus, whose body radiates light, is the focal point of Caravaggio’s painting. In the Telegraph’s picture, the Ukrainian soldier’s torso, bathed in bright light, is the focal point. The soldier’s arm is also bathed in light, and like the arm of Christ in Caravaggio’s picture, points towards the ground, falling directly under his torso, becoming another focal point. In this way, we can interpret the light emanating from the wounded and suffering bare flesh as an allusion to sacrifice and saintliness.

But it is not just the use of light and dark that alludes to classic imagery of Christ and sacrifice. The composition of the figures plays a role too. It mirrors the diagonal pattern of form and movement seen in paintings where Christ is the focus under spotlight. We see diagonal movement in Caravaggio’s painting, from the hands of Mary Clopas (top right), to Mary Magdalene’s shoulder, to Nicodemus’s elbow and Christ’s torso.

Another example of diagonal movement is seen In The Dead Christ Mourned by Annibale Carracci, in which the eye is guided through the use of pattern of movement to rest upon the crucified Christ, the focus.

In the Telegraph’s picture we see a diagonal composition, although as the fifth man is concealed in the darkness, he does not form part of the composition. The medic on the right is standing tall, peering down at the soldier, the medic in the middle is slightly inclined over the soldier and the medic on the left is bent over the soldier’s head. This creates a circular composition, but the medics’ heads create a diagonal composition too, guiding the gaze from one head to another, to finally land on the suffering soldier’s.

The Telegraph could have chosen to publish any number of images showing the dead and rotting bodies of Ukrainians, left on the battlefields, unattended. But pictures of piles of mutilated corpses scattered across Ukraine would horrify and not win over Western audiences. Instead, like other Western corporate outlets, it chooses to publish images of those hanging on to life, for we are to believe this soldier is still alive. Are we to gather then that the mutilated and barely living Ukrainian can serve a purpose for the corporate media in a way that the dead cannot?

From the outset NATO leaders and their obedient Western media have presented the Russia-Ukraine conflict as good versus evil, right against wrong. For their efforts to militarise Ukraine to continue, they must reinforce this narrative. For this to succeed, the dehumanisation and exploitation of Ukrainians as sacrificial fodder must go on, peace must be seen as betrayal, if not blasphemy. And is the war addict NATO media manufacturing our consent for the destruction of Ukraine and Ukrainian life? Its portrayal of the Ukrainian as the object of sacrifice suggests this is so.