Sputnik interview with Prof. Marcello Ferrada de Noli, The Indicter chief editor.

It is the UK government, not the UK courts that ultimate decide on the extradition issue

. The determinant decision around this case is not the one taken today by the court. Instead, the most relevant judgement is the one taken by the UK government. I explain: There is a widespread notion, fueled by the UK authorities themselves, that a final decisions on extradition issues in Great Britain is a matter of the courts of justice. That notion is utterly mistaken.

For instance, in 1998, the former Chilean fascist dictator Augusto Pinochet was in London for some medical treatment. Some members of the European judiciary and other academics –among myself, at that time professor in Norway– requested the extradition of Pinochet. In my case I requested him to be taken to an European court for war crimes and systematic violations of human rights. [1] The UK courts approved the extradition, but finally the UK executive power intervened and annulated the extradition decision, thus allowing Pinochet to return to Chile without being processed for the crimes he committed on behalf of the power that installed him at the Chilean government via a bloody coup –meaning the U.S.

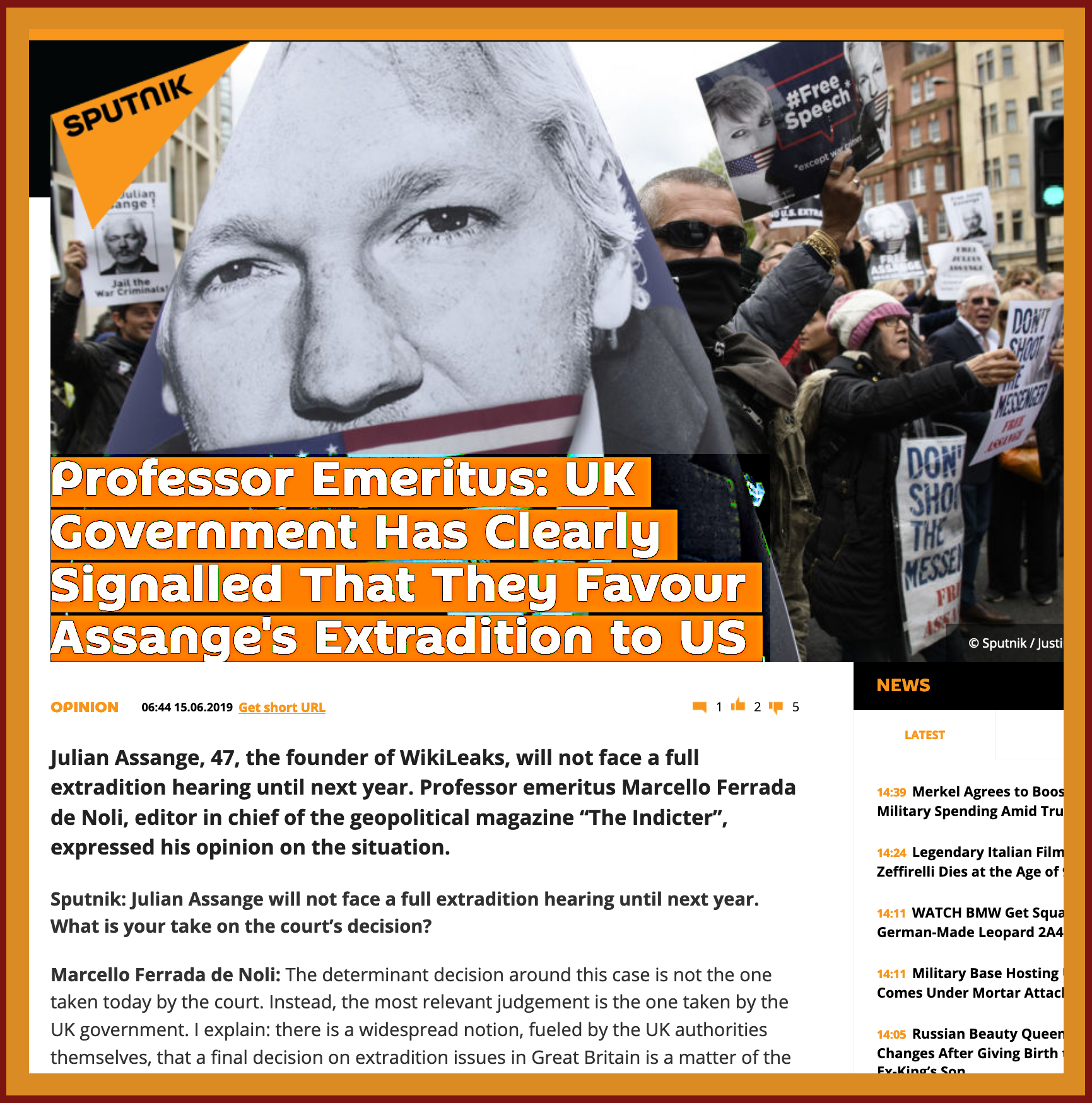

In the case of Assange, the UK government has clearly signaled that they favour his extradition to the U.S. –Foreign Minister Jeremy Hunt recently declared that he was not going to block an extradition of Assange to de U.S. [2] [3] And now the Home Office has confirmed that U.K. has signed the extradition order regarding Assange. [4] So, what the court shall finally decide in 2020 is not final in terms of the extradition fate of Julian Assange.

We have to take into consideration that the exposures of WikiLeaks in regards to the occupation wars of Iraq and Afghanistan also had repercussion in terms of the responsibilities of the UK armed forces, which are US closest allies in a variety of such military interventions, including illegal ones. To this has to be added the relatively recent spreading by WikiLeaks of revelations around the UK’s “Integrity Initiative”.

What are the reasons for this delay?

The U.S. Justice Department has received much criticism, including from some own ranks, on the partly technically-deficient and partly inappropriate juridical construction of the accusations gathered against Julian Assange.

The U.S. Justice Department has received much criticism, including from some own ranks, on the partly technically-deficient and partly inappropriate juridical construction of the accusations gathered against Julian Assange.

One conceivable reason of this delay is that it gives time to the U.S. authorities to a) partly prepare a better presentation at the courts to ‘base’ their extradition request, and b) partly to campaign both domestically and internationally on the legitimacy of this indictment.

Such indictment against Assange, which has been sought for his activities in WikiLeaks, has a direct impact in the institutions of freedom of expression and freedom of the press. This is theme that since long has been taken up by academics, professors, Nobel Prize laureates and human rights organizations including Swedish Doctors for Human Rights (SWEDHR). [5]

Now, after the dramatic eviction and arrest of Assange at the Ecuadorian Embassy and the subsequently U.S. extradition request, the issue has gradually being in the focus of Western stream media and a variety of journalist organizations –which in the U.S. are obliged to connect the issue with infringements to the Fifth Amendment.

Against that background, the U.S. authorities are in the need to convince about the legitimacy of the accusations against Assange which entail the publication of secret materials –which is a journalist/publicist endeavour that many mainstream outlets have also indulged in (including, previously, in partnership with WikiLeaks). For that the U.S. authorities need some time, and that time is now been provided by the decision of the U.K. court.

Do analysts have the right, or facts-ground, to imply that courts would be working not as separate constitutional powers –as it should be– but instead under a common strategy with their governments? Or that governments in the West could intervene in decisions that nominally would be the domain of its legal-system or judicial authorities?

My opinion is, that is exactly the case. For example, in the Assange case, a Snowden document reveals that the prosecution of Assange was requested in 2010 by the US, to the countries participating in the Afghan war under U.S. command –such as Sweden. [6]

And furthermore, it has been already revealed in the treatment of the Assange case, that prosecutors authorities in one NATO country such as U.K,. could intervene in the prosecutors’ activities of another country such as Sweden. At that opportunity, it was the UK prosecutors asking Swedish counterparts to protract the investigation of Julian Assange –and not to close the extradition case, as it has been considered in Sweden. (The Guardian, 11 Feb 2018) [7]

References

[1] Assange, Montgomery and Pinochet. The Professors’ Blog, November 4, 2015.

[2] British foreign secretary says he wouldn’t block extradition of Julian Assange. CBS News, June 2, 2019.

[3] @Professorsblogg on Twitter, June 4, 2019.

[4] Sajid Javid signs US request for extradition of Julian Assange. The Times, June 14, 2019.

[5] Over 60 professors, four Nobel Prize winners, demand UK to respect the UN ruling on Assange’s freedom. The Professors’ Blog, August 8, 2016.

[6] Sweden doesn’t follow U.N., but U.S. – Prosecution of Assange requested by the US, Snowden document reveals. The Indicter magazine, February 2016 issue.

[7] Sweden tried to drop Assange extradition in 2013, CPS emails show. The Guardian, February 11, 2018.