By Marcello Ferrada de Noli

Professor Emeritus. Frm Head of the Research Group on Cross-Cultural Injury Epidemiology, Karolinska Institute, Dept Public Health Sciences, Sect. Social Medicine, and frm Research Fellow at Dept Social Medicine, Harvard Medical School.

This paper is available as a SocArXiv preprint: DOI https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/2ryqd_v1

Description

METADATA

Contributors

Date Created

Feb 5, 2026, 6:26 PM

Date Updated

Feb 6, 2026, 6:57 PM

License

CC-BY Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International

Subjects

Social and Behavioral Sciences, Medicine and Health Sciences

Abstract

This paper applies a political-epidemiological framework to analyse the long-term human consequences of U.S. interventions in Latin America from 1846 to 2026. Using historical documentation, political analysis, and epidemiological aggregation, the study identifies a cumulative burden exceeding 500,000 estimated fatal and non-fatal victims, including deaths, injuries, and enforced disappearances. The figures are derived from national truth commissions, international human rights bodies, and established historical syntheses. The results show that the majority of casualties occur not during direct military interventions but through post-intervention authoritarian governance, regime repression, and institutionalised violence. Interventions are thus conceptualised not as isolated military events but as regime-transforming processes that restructure state power and generate temporally distributed patterns of harm. The study formalises political epidemiology as a population-health framework and introduces political injury epidemiology as a specialised analytical domain for the study of fatal and non-fatal injuries produced by political power systems. Together, the findings support a unified causal model linking intervention, regime formation, repression, and population-level injury and mortality, reframing foreign intervention

INTRODUCTION

This paper updates and extends my previous study, expanding the temporal scope to 1846–2026 and revising the casualty synthesis. In my previous report, the human costs of US interventions in Latin America from 1954 to 2025 were considerable: the combined total of victims across all categories amounted to figures around half million lives or people affected –– encompassing both fatal and non-fatal injuries, as well as disappearances. Economically, US corporations’ profits were estimated at between $2.8 and $3.3 trillion during the period studied (Ferrada de Noli 2026).[1]

The Evolution of the Monroe Doctrine: From Principle to Policy Instrument

President James Monroe, the fourth president in the history of the United States (serving from 1817 to 1825), is widely recognised for articulating a geopolitical strategy which has constituted a landmark in U.S. foreign relations policy since the declaration was introduced in 1823.

The doctrine was initially presented as a measure to deter further colonial encroachment in Latin America by European powers. Its stated aim was to protect the sovereignty and independence of emerging nations in the region. President James Monroe delivered an unequivocal message to the international community: the United States would not permit any further colonization of the Americas by European powers.

This stance asserted that the United States would not accept any future colonisation attempts by European powers within the Americas. (Howe 2007) [2] It was unequivocally designed to safeguard the sovereignty and independence of the newly emerging nations in Latin America: by explicitly stating that any efforts by European countries to establish new colonies in the Western Hemisphere would be intolerable, Monroe set a precedent in American foreign policy. As quoted by Howe, Monroe insisted the U.S. would not tolerate “future colonization by any European power” anywhere in the Americas (Mark 2006) [3] .

During the early decades of the 1800s, a significant transformation unfolded in Latin America as several countries successfully achieved independence from colonial powers such as Spain and Brazil. This era was marked by a series of military campaigns that ultimately brought an end to European colonial domination in the region. A central figure in these liberation movements was the Venezuelan general Simón Bolívar, who played an instrumental role as the chief architect of the military campaigns that led to the emancipation of first Venezuela, and then of other Latin American nations (Lynch 2006 [4]).

However, the practical implications and applications of the Monroe Doctrine evolved over time. Notably, during the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt (1901–1909), the doctrine’s interpretation shifted significantly. It became increasingly evident that, beyond its original purpose, the Monroe Doctrine provided a platform for justifying United States intervention in Latin American affairs (Gilderhus 2006).[5]: it transformed into a rationale for U.S. involvement, moving from a defensive stance against European colonial ambitions to an active policy instrument for asserting American influence within the Western Hemisphere and particularly regarding Latin America.

Humanitarian Rhetoric

As such, this foreign policy made empirical debut with the onset of the Mexican American War. Although the primary impetus for the conflict was a territorial dispute, the United States justified its actions through humanitarian rhetoric, claiming an intention to liberate “oppressed populations.” Nevertheless, the outcome of the war favoured the United States, resulting in significant territorial expansion and the extension of the nation’s borders.

These humanitarian justifications argued during the Mexican war continue to resonate in contemporary U.S. geopolitical assessments and official statements, for example regarding regions such as Venezuela and Greenland. Nonetheless the emphasis made on human concerns, these arguments are frequently accompanied by references to national security and the economic exploitation of natural resources.

For instance, in January 2026, the doctrine’s principles were invoked to justify intervention in Venezuela, culminating in the capture of President Nicolás Maduro. In a press briefing, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio underscored the hemispheric focus of American policy by declaring, “Latin America is in our hemisphere.” [6]

Between the administrations of President James Monroe and President Donald Trump, the United States has engaged in a total of 51 interventions across the Americas. These interventions have taken various forms, including direct military invasions, the financing of opposition or rebel forces, support for coups d’état, and the backing of dictatorships or right-wing authoritarian governments that emerged from such power shifts. This pattern would demonstrate the persistent use of the Monroe Doctrine as both a foundation and a justification for U.S. involvement in the political affairs of Latin American nations.

Human Losses and the Persistence of Repression Following Military Interventions

This investigation is primarily focused on the epidemiology of fatal, non-fatal injuries and other human losses associated with war, specifically those that arise from military coups and the dictatorships that often follow such takeovers. A key argument presented here is that the toll on human life and well-being does not conclude with the cessation of immediate hostilities or armed confrontations linked to the initial military intervention. Instead, rather than a prompt restoration of democratic governance, the more typical outcome is the institution of protracted authoritarian regimes.

During these extended periods of dictatorship, there is a marked escalation in both fatal and non-fatal injuries among the affected population. For instance, after the Chilean coup in 1973, the highest numbers of killings and enforced disappearances were recorded not during the coup itself, but in the subsequent years as the military entrenched its power.

Furthermore, it is commonplace for resistance efforts to persist well beyond the initial coup, sometimes continuing for months or even years under the rule of military or military-backed civilian governments. Such ongoing resistance frequently results in additional deaths, injuries, and enforced disappearances.

In summary, the pattern of casualties linked to military interventions is largely determined by the degree and duration of repression imposed by the military upon assuming control, and these patterns often persist throughout the lifespan of the dictatorship.

Political Epidemiology: A Framework for Analysing the Impact of Political Structures on Population Health

In that context, this study applies a political epidemiology framework to examine the effects of political actions on population health within the context of U.S. interventions in Latin America. For which, I defined political epidemiology as follows:

Political epidemiology is a field of epidemiology science that examines the qualitative and quantitative impact that political developments, institutions, and power structures have on population health, mortality and life expectancy. It focuses on how human-generated political phenomena ––such as war, military interventions, coups d’état, regime formation and institutionalized repression––function as macrosocial determinants of health at the population level.

Within this broader field, Political injury-epidemiology constitutes a specialized analytical domain concerned specifically with the distribution, determinants, and outcomes of both fatal and non-fatal injuries produced by political processes. This subfield focuses on injury, disability, and mortality resulting from war, regime violence, repression, and political conflict, treating injury production as an epidemiological process mediated by political power structures and institutional systems.

In systematic analysing the ways in which population-level patterns of injury, mortality, and harm are shaped by political structures, institutional arrangements, and regimes of governance, political epidemiology contrast to approaches that focus on isolated incidents or individual experiences: the political epidemiology framework emphasizes the collective and structural nature of health outcomes resulting from political processes.

Central to this approach is the recognition of repression as a fundamental structural determinant of population health. Rather than viewing acts of violence and their consequences as singular or disconnected events, the framework posits that the production of casualties is closely linked to political mechanisms and decisions. Specifically, casualty production is understood as an epidemiological process that is politically mediated ––emerging as a result of regime formation, the institutionalization of coercive practices, and the prolonged exercise of authoritarian governance.

By adopting this perspective, this study seeks to contextualize patterns of injury and mortality within broader historical and political dynamics. It allows for a comprehensive understanding of how governance systems and institutionalized repression contribute to both immediate and long-term health outcomes for affected populations.

Lasting Impact of U.S. Interventions

The magnitude of individuals affected by U.S. interventions in Latin America serves as a stark demonstration of the wide-reaching and persistent repercussions of these policies. This figure poignantly illustrates not only the immediate human toll, but also the enduring disruption and suffering experienced by the region’s populations and societies. The consequences extend beyond the cessation of direct hostilities, manifesting in ongoing loss of life, injury, and the long-term destabilisation of communities. Such outcomes underscore the profound and enduring effects of U.S. foreign policy actions on the fabric of Latin American nations, shaping their trajectories for generations.

Psychic Injuries and Non-Fatal Harm Resulting from Military Interventions

An important category among non-fatal injuries resulting from military invasions, coups, and the subsequent repression is represented by psychic injuries. These psychological effects have been the subject of research within the field of psychiatric epidemiology. Notably, a range of diagnoses has been identified as prevalent among populations exposed to such traumatic events, with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) being the most frequently observed condition. In addition to PTSD, other mental health outcomes have been documented, including various forms of suicidal behaviour, depression, and personality disorders [7].

These findings underscore the profound and lasting impact that political violence and sustained repression can have on the mental health and well-being of affected individuals and communities.

Theoretical Framework: Structural Violence and Social Suffering

This study adopts a structural violence framework to examine the underlying sources and mechanisms of harm within societies. Instead of locating the causes of suffering in isolated events or the actions of individuals, this approach highlights how political and institutional systems consistently produce and maintain harm over extended periods. Central to this framework is Farmer’s influential conception of violence, which argues that suffering is not a matter of chance; rather, it is historically patterned and systematically organized through institutional arrangements (Farmer 1996; [8] Farmer 2003 [9]).

Further enhancing this perspective, the framework incorporates Kleinman’s concept of social suffering. This notion recognizes that both collective and individual distress arise from politically structured circumstances. Kleinman, Das, and Lock (1997) [10] emphasize that social suffering is generated by broader political and institutional environments that influence everyday life, as opposed to being the outcome of isolated incidents. By drawing on these theoretical contributions, the study aims to clarify how both historical and ongoing systemic forces shape the lived experiences of harm and suffering among affected populations.

Aims

The present study aims to complete the data of previously reported U.S. interventions in Latin America, extending the study period with the segment 1846–1954 (prior to the invasion in Guatemala 1954), and to draw a political–epidemiological pattern of the series.

Methods

Study Design and Analytical Framework

This study takes a historical–epidemiological perspective, grounded in political epidemiology and the structural violence framework. It treats military interventions not as isolated incidents but as ongoing processes capable of transforming ruling regimes, reorganising state authority, and reshaping systems of violence within societies affected by such actions.

Rather than analysing individual military acts in isolation, the research examines the broader political structures and institutions that emerge after interventions. Expanding the focus in this way enables the study to address the lasting and systemic effects that interventions have on state development and repression mechanisms.

The analytical approach uses a causal systems model, which suggests that external intervention acts as a trigger for political transformation. This process involves regime takeovers, leading to institutionalised repression and a redistribution of violence across time. Consequently, casualty rates are seen as part of an ongoing process, rather than being confined to one-off events.

This methodology makes it possible to include different types of harm within a single epidemiological framework. It specifically accounts for deaths resulting from war, violence linked to coups, and casualties from post-intervention repression. By bringing these components together, the model seeks to provide a comprehensive picture of the harm produced by interventions.

Definition of Intervention

For the purposes of this study, “intervention” is defined as any action by the United States that directly or indirectly alters the political order within a Latin American state. Such actions encompass a spectrum of coercive mechanisms, including military, financial, and institutional methods.

Intervention includes practices such as direct military invasions, occupations, and proxy warfare or paramilitary operations executed with U.S. support. The term also covers instances where the United States finances, arms, or trains opposition groups and rebel forces, thereby influencing internal conflicts and power dynamics.

Furthermore, intervention comprises support for coups d’état, which may involve various forms of assistance aimed at facilitating or consolidating regime change. Diplomatic and economic pressure, used to achieve political transformation or undermine existing governments, also falls within this scope.

Additionally, the definition encompasses U.S. backing of authoritarian regimes established through military takeovers, as well as structural military assistance designed to enhance a state’s repressive capacities.

By employing this comprehensive definition, the study intentionally expands its focus beyond battlefield engagement. It acknowledges that both enabling and structural interventions—such as those reshaping a state’s coercive infrastructure or authority—are crucial for understanding the long-term effects of U.S. involvement in the region.

Case Identification and Inclusion Criteria

Intervention cases in this study were identified by examining historical records, academic sources, archival materials, and declassified documents. Each case needed documented evidence of U.S. involvement that met at least one pre-established operational criterion; mere diplomatic disputes or rhetoric were excluded. Only interventions with a verifiable political and coercive impact on state structures and confirmed through multiple credible sources were included, ensuring analytical consistency and reliability.

Data Sources

Historical and Political Sources

The research relies on both primary and secondary historical sources to determine intervention timelines, regime changes, and repressive systems. These include:

- archival records,

- declassified government documents,

- academic historiography,

- Official investigations,

- truth commission reports,

- judicial records,

- scholarly monographs and peer-reviewed journal articles.

Collectively, these materials support the identification and confirmation of intervention events.

Epidemiological and Casualty Data

Casualty data were obtained from the following sources:

- national truth commissions

- forensic anthropology reports

- human rights documentation

- judicial investigations

- public health and epidemiological studies

- NGO and international organization databases

In instances where discrepancies were identified among sources, conservative estimates and ranges were utilized to ensure accuracy and reliability.

Casualty Classification System

Casualties are grouped into three main categories:

- Fatal injuries

- Non-fatal injuries

- Missing/disappeared persons

These classifications allow for consistent documentation across various contexts. Psychological harm is excluded from quantified data due to a lack of standard diagnostic records and ethical limits on data use; its impact is discussed through references to prior research rather than new analysis.

Causal Attribution Framework

Causal attribution is structured within a framework that emphasizes political and institutional continuity over isolated events. This approach recognizes three analytically distinct yet causally related levels of attribution:

Direct causation: Refers to casualties occurring during military operations, invasions, coups, or intervention episodes.

Enabling causation: Relates to casualties resulting from regimes and security forces that have been established through external political, military, or financial assistance.

Structural causation: Involves casualties arising from repressive systems institutionalized following regime consolidation, including sustained repression, counterinsurgency activities, and suppression of resistance.

This framework underscores the causal continuity linking intervention, regime establishment, and subsequent repression. Consequently, acts of violence under post-intervention authoritarian regimes are considered causally connected to the preceding intervention that facilitated the consolidation of power.

Temporal Distribution of Violence

Violence is conceptualized as being distributed over time rather than confined to isolated events. Military coups and invasions are regarded as initial catalysts that restructure state-led violence, rather than definitive endpoints. Repressive measures, counterinsurgency operations, and the suppression of resistance often continue for extended periods, resulting in prolonged patterns of mortality and injury.

Consequently, casualty production is analysed as a phenomenon at the regime level, rather than on the scale of individual battles. This approach facilitates the integration of deaths, disappearances, and injuries resulting from post-coup repression into a unified causal framework alongside war-related casualties.

Quantification Strategy

Quantification uses a conservative aggregation strategy based on:

- minimum verifiable estimates,

- documented ranges (not inflated values),

- excluding speculative figures,

- not extrapolating beyond sources,

- and clearly noting data gaps.

Only well-documented cases were included in numerical totals; others were analysed but not counted numerically when reliable data was lacking.

Periodization and Segmentation

The data are organized into three distinct historical segments (1846–1933, 1934–1953, 1954–2026) to ensure methodological transparency and clarity of evidence. This segmentation is based on variations in documentation quality, intervention approaches, and data reliability. It serves as a presentation framework rather than indicating any causal separation; for analytical purposes, all periods are considered integral parts of an ongoing intervention–repression system.

Ethical and Epistemological Considerations

This study acknowledges that casualty figures indicate only documented harm and cannot fully express the broader impacts of repression and political violence. Quantification is used as an analytical tool, not a full account of suffering. Epistemologically, the study rejects event-based reductionism and instead focuses on structural factors—institutions, regimes, and systems—as central to generating harm.

Summary of Analytical Logic

Intervention → Regime Capture → Institutionalized Repression → Distributed Violence → Casualty Epidemiology

This sequence forms the study’s main analytical framework, guiding case selection, attribution, measurement, and interpretation.

RESULTS I: INTERVENTIONS

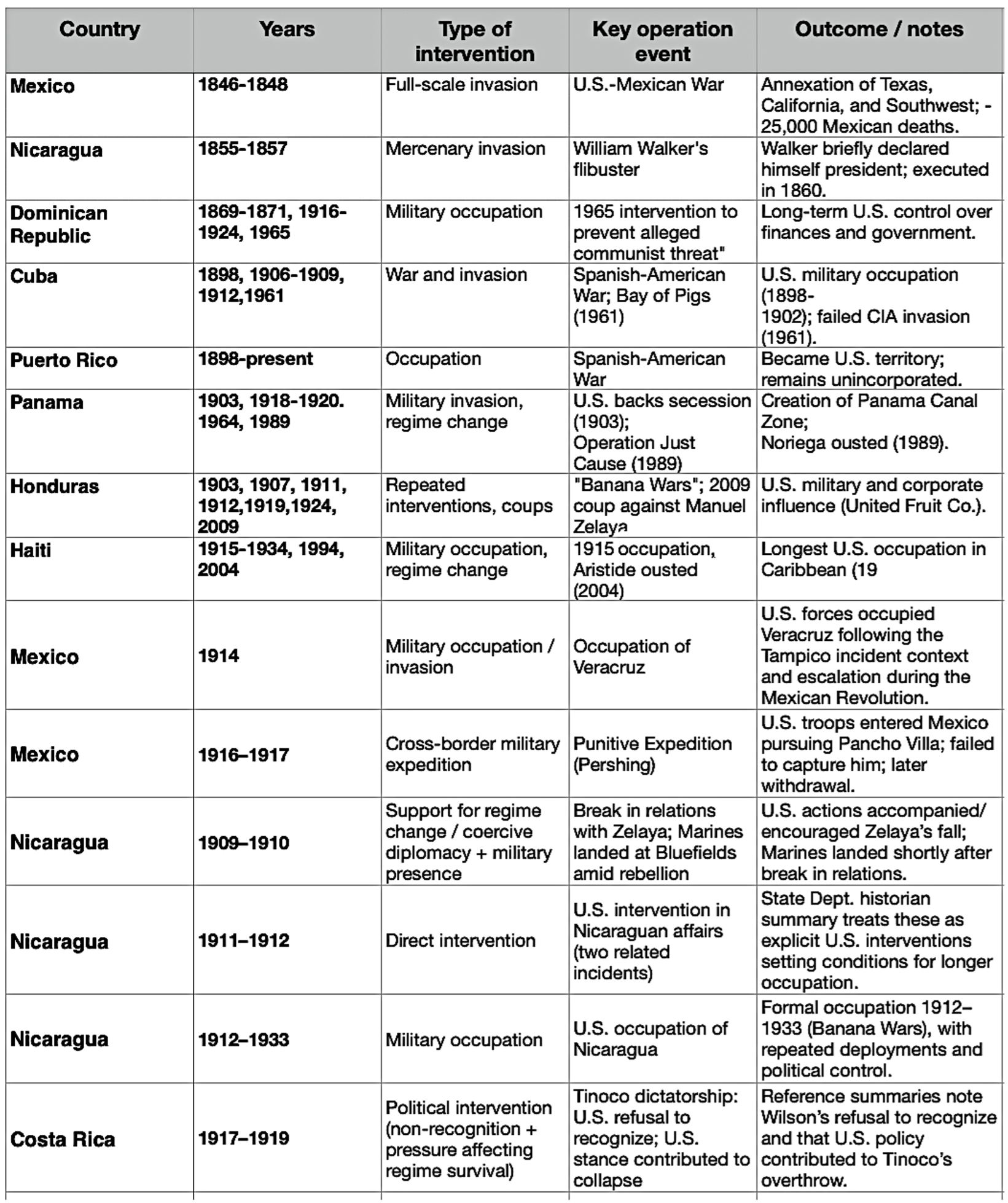

TABLE 1: U.S. Interventions in Latin America, 1846–1933

Total n= 23 interventions, period 1846–1933

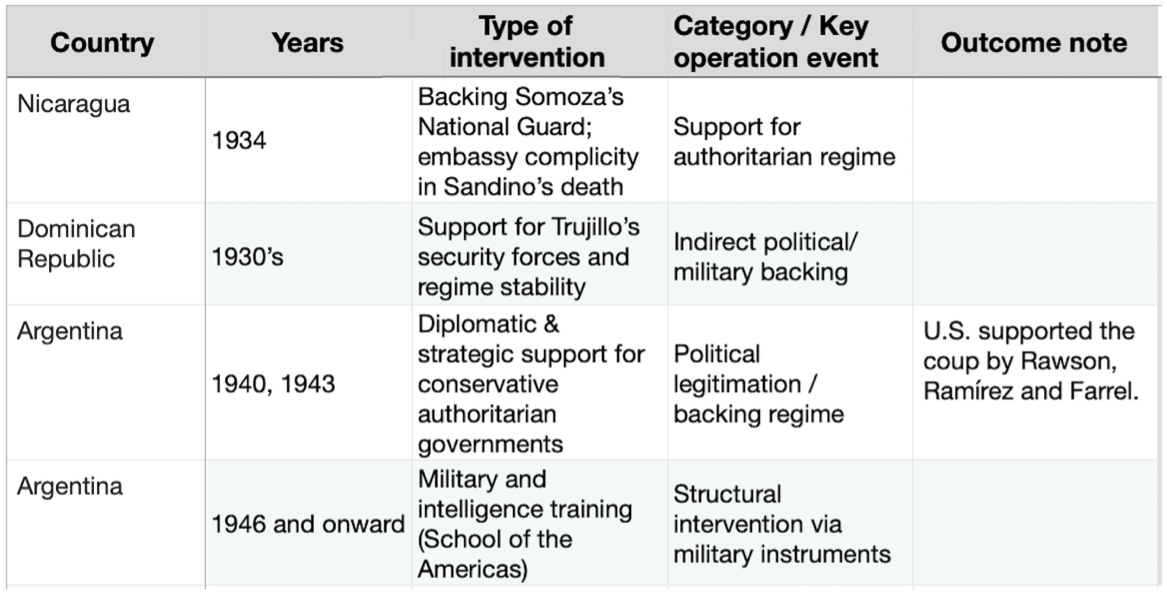

TABLE 2: U.S. Interventions in Latin America, 1934–1953

Total n=4 interventions, period 1934–1953

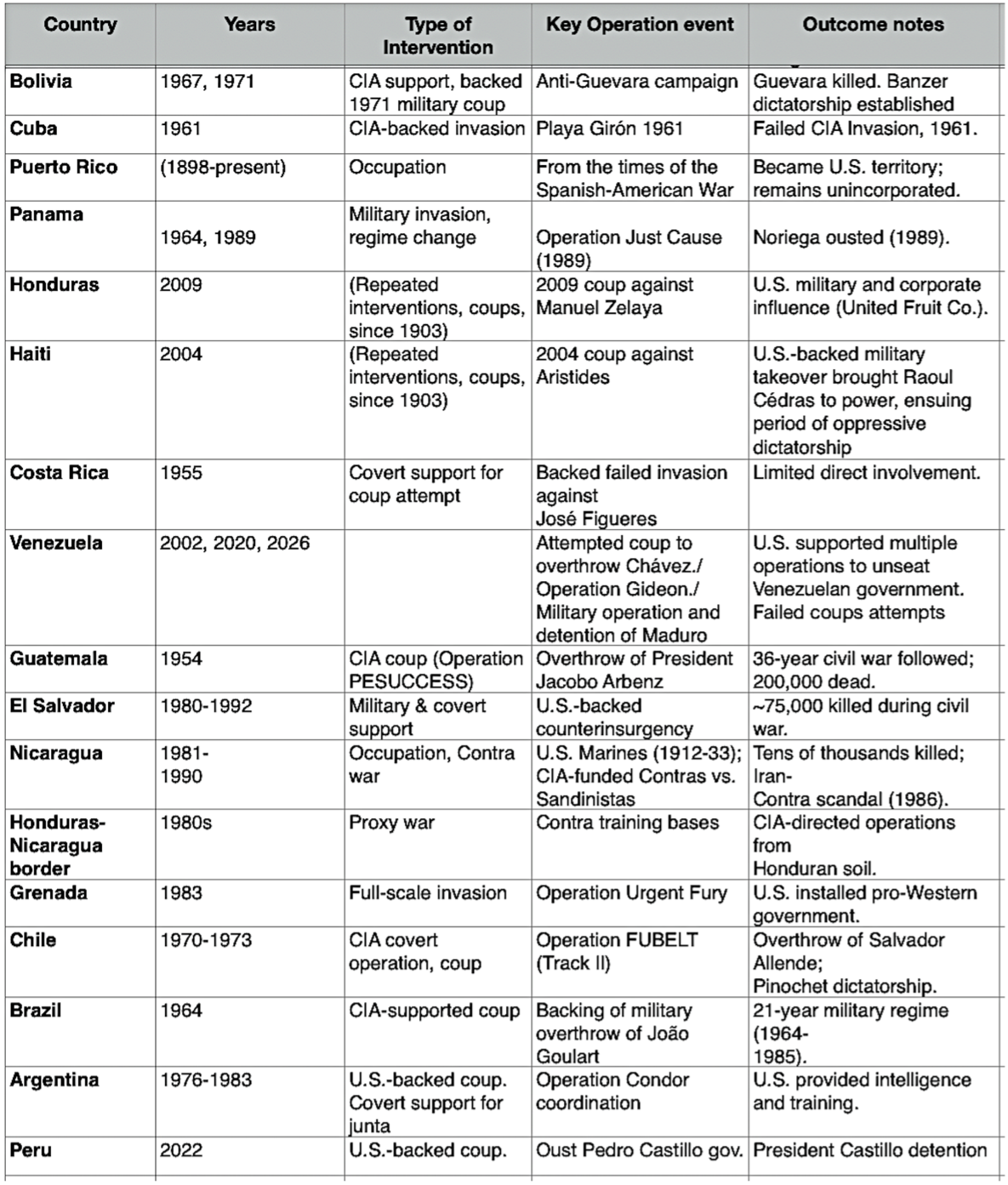

TABLE 3: U.S. Interventions in Latin America, 1954–2026

Total n=21 interventions, period 1954–2026

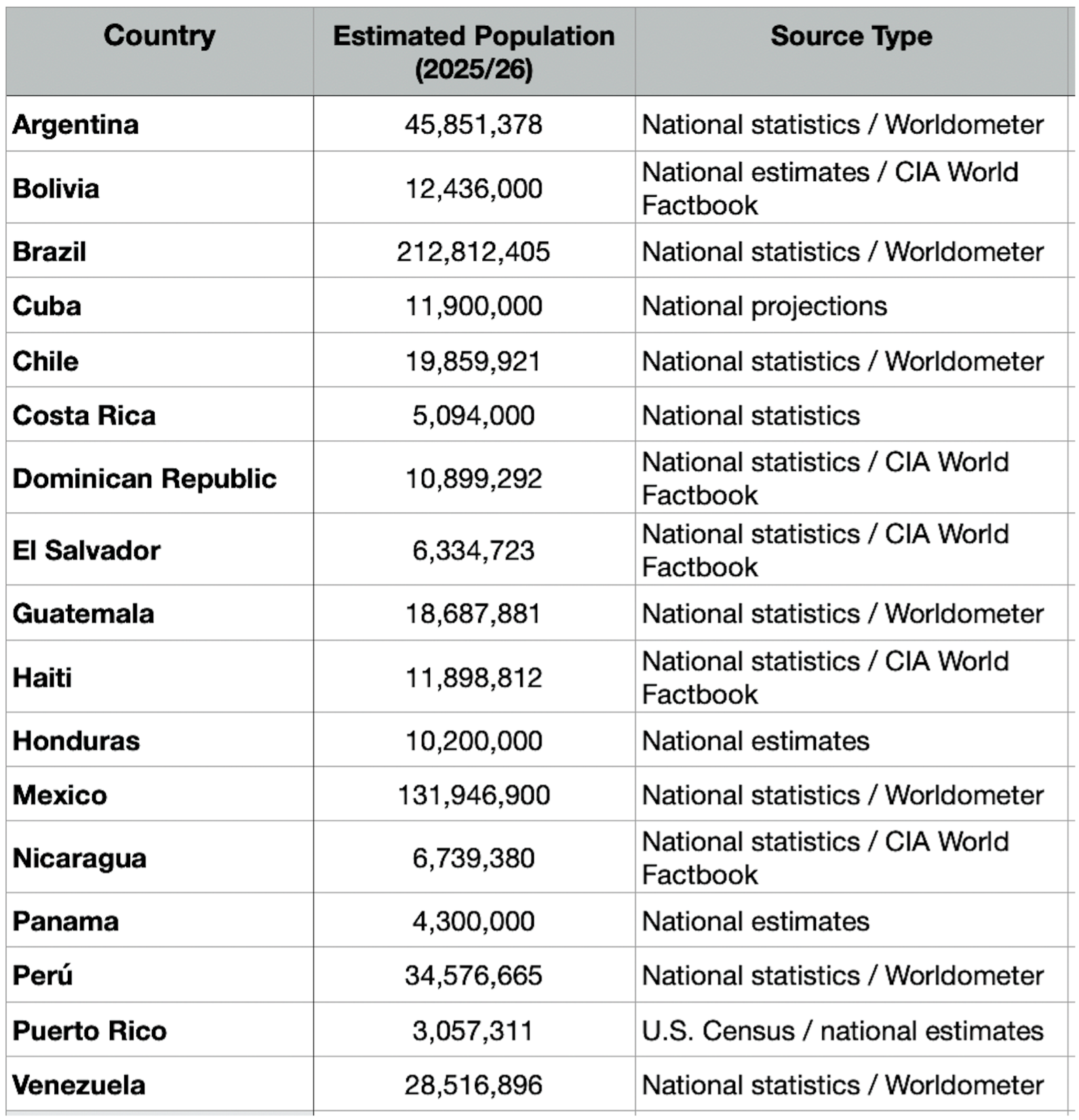

TABLE 4: Population and Regional Share of Latin American Countries Subjected to U.S. Interventions

Note: The population numbers are based on the latest national estimates and demographic forecasts for 2025–2026, provided by national statistical offices, Worldometer, the CIA World Factbook, and official census data. These values are approximate mid-year estimates, and slight differences may appear depending on the source or methodology used for projections.

2. Overview of Intervention Landscape

Total Number of Documented Interventions

In the all-inclusive study period of 1834-2026, the U.S. performed a total of N= 48 interventions in Latin American countries.

The number of countries intervened were n= 17 out of total 24 Latin American Countries,[11] or 70.83 %.

The countries subjected to U.S. intervention were found to be Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Cuba, Chile, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Perú, Puerto Rico, y Venezuela. In some of the listed countries, several interventions occurred across different years. Altogether, the population of these countries that have experienced at least one U.S. intervention, is estimated in about 569 million people.

Being the total population of Latin American countries N= 628,098,749, the population of the countries intervened by the U.S. across the period studied represent 90,6 % of the total Latin American population.

Total population of intervened countries:

≈ 569,105,663

Latin America Total population (reference value):

N = 628,098,749

Derived Indicator:

Geographic Distribution

Countries subjected to three or more interventions were:

- Cuba

- Dominican Republic

- Haiti

- Honduras

- Nicaragua

- Panama

- Venezuela

Countries subjected to two interventions were:

- Argentina

- Bolivia

- Mexico

Countries subjected to one intervention were:

- Brazil

- Chile

- Costa Rica

- Grenada

- Guatemala

- El Salvador

- Perú

Interventions are not evenly distributed across the region but instead demonstrate distinct geographic patterns. Certain countries and subregions have experienced higher frequencies of intervention, indicating a targeted or strategic focus within the broader landscape.

Modalities of Intervention

- Direct Military invasion/occupation (involvement featuring overt deployment of armed forces, occupation, or direct combat operations within the target territory): Cuba, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Nicaragua, Mexico, Panama,

- Covert Operations: Actions conducted with an emphasis on secrecy, including intelligence activities, clandestine missions, or support for undercover efforts to influence political or military outcomes.

- Coup Support: Provision of resources, expertise, or backing to internal or external actors seeking to overthrow or replace existing governments through unconstitutional means: Chile,

- Proxy Warfare: Use of third-party groups or allied forces to pursue strategic objectives, often resulting in indirect engagement and plausible deniability for the intervening power: Nicaragua

- Regime Backing: Sustained support for incumbent governments, including economic, political, or military assistance designed to maintain or reinforce existing leadership structures:

- Structural Military Assistance: Long-term involvement aimed at reshaping or strengthening the military institutions of targeted countries, often encompassing training, advising, and institutional reform: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Honduras, Mexico, Panama, Perú, Uruguay y Venezuela.

Note: Although Paraguay and Uruguay are not listed in the Result Tables above, also participated –– together with the countries named above– in the counter insurgence training programs given at the U.S. “School of the Americas”, previously located in the Panama Zone (Gill, 2004)[12]. Between 1970 and 1979, military personnel from Chile, Colombia, Bolivia, Panama, Perú, and Honduras comprised sixty-three percent of the student body at the school. In the 1980s, students from Mexico, El Salvador, and Colombia accounted for seventy-two percent of enrolled cadets. [13]

Patterns of Intervention: Political Penetration, Regime Transformation, and Coercive Restructuring

The documented interventions throughout the region consistently reveal recurrent patterns in their nature and impact. Firstly, there is a clear trend of political penetration, wherein external actors systematically insert themselves into the internal political processes of targeted states. This involvement often shapes the political direction and decision-making within those countries.

In addition, interventions frequently result in regime transformation. This encompasses efforts to alter, replace, or fundamentally restructure existing governmental systems, whether through overt or covert support mechanisms. Such transformations are marked by the reorganisation of leadership and the establishment of new political orders.

Alongside these changes, a persistent element is coercive restructuring. Intervening forces employ various forms of pressure—ranging from direct military action to indirect support or institutional reform—to reshape the political and military landscapes of the affected states.

While the specific modalities of intervention have shifted over time, adapting to changing strategic contexts and operational preferences, the underlying structural effects—namely, the penetration of political systems, transformation of regimes, and coercive reorganisation of state structures—have demonstrated continuity across different periods and cases.

Temporal Distribution of the Interventions

- The period following 1959 is characterized by a significant escalation and formalization of U.S. interventionist activities in Latin America. This intensification is directly linked to the broader context of the Cold War, during which U.S. foreign policy placed heightened emphasis on securitization and the doctrine of containment. The aftermath of the Cuban Revolution served as a pivotal turning point, prompting the United States to adopt more systematic and coordinated strategies aimed at shaping regional regimes and countering insurgent movements.

In this era, U.S. interventions became not only more frequent but also more deeply embedded within institutional frameworks. The development and implementation of comprehensive regime-formation policies and counterinsurgency operations reflected a deliberate effort to influence political outcomes and maintain stability in the Western Hemisphere, consistent with the strategic imperatives of the Cold War. The post-1959 period thus marks a transition toward an intervention model defined by both greater intensity and organizational sophistication.

- The empirical record demonstrates that major global conflicts, specifically the two World Wars, significantly influenced the frequency and character of U.S. intervention in Latin America. During periods of extensive U.S. military mobilization, such as World War I and World War II, as well as in the immediate aftermath of these wars, there was a noticeable decline in the initiation of new intervention operations across the region.

This reduction can be attributed to several interrelated factors. Strategic priorities shifted as the United States focused its resources and attention on broader global theatres of war. Logistical limitations, including the allocation of military assets and personnel to primary conflict zones, further constrained the country’s ability to sustain or initiate new interventions in the Western Hemisphere. Additionally, the geopolitical landscape following each world war entailed new constraints and considerations, limiting the feasibility and desirability of direct intervention in Latin American affairs during these critical periods.

Consequently, the pattern of reduced intervention during times of global military engagement and post-war transition underscores the significant impact that international strategic demands exerted on the United States’ capacity and willingness to intervene in its neighbouring region.

- Preliminary analysis suggests that major U.S. recessions coincide with less intervention in Latin America, while such activity usually resumes after economic recovery.

An examination of intervention trends reveals a relationship between U.S. domestic economic conditions and the frequency of intervention activities in Latin America. Specifically, periods marked by significant economic downturns in the United States are associated with a discernible reduction in intervention initiatives within the region. During times of pronounced economic contraction, intervention activity tends to diminish, reflecting a deprioritization of external engagements amidst acute domestic challenges.

Following these downturns, the resumption of intervention efforts is typically observed during the subsequent phases of economic recovery. Rather than initiating new intervention initiatives during periods of domestic economic strain, the United States appears more likely to renew such activities once economic stability and growth have been reestablished. This temporal pattern suggests that the capacity and political will to undertake interventionist policies in Latin America are closely linked to the broader trajectory of the U.S. economy.

RESULTS II: CASUALTIES

TABLE 5: Estimated Victims by Country, Due to U.S. Miliary Interventions, Coups and Repressions

* “Other Non-Fatal Victims (Broad)” refers to cases of non-fatal political repression, which can include torture, forced disappearances not confirmed as deaths, arbitrary detention, and other documented forms of political harm. These definitions may vary depending on country-specific sources and reporting practices.

** Chile: The number of people killed or disappeared differs by source; about 3,000 is the officially recognized count for deaths and disappearances according to the Rettig Report, while higher numbers are based on broader historical research. The estimated 40,000 figure represents survivors of political imprisonment and torture (Valech, 2004, 2011)[14], not fatalities.

*** Mexico (1846–1848): According to Clodfelter (2017), fatality counts include both military and civilian deaths from combat, disease, and other conflict-related causes. As a result, Mexican figures are not directly comparable with statistics that only account for combat or repression-related deaths.

Note: Sources of data on casualties are listed in Appendix 1.

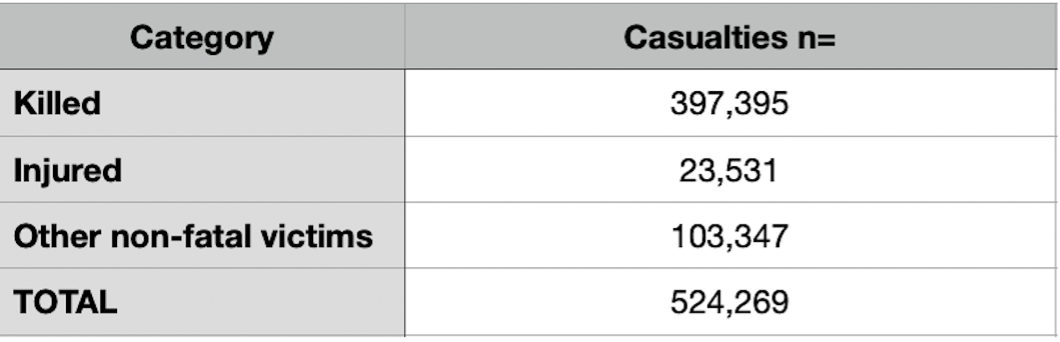

TABLE 6: Aggregated Casualties 1848–2026 (est.)

Killed n= 397,395

Injured / wounded n= 23,531

Other non-fatal victims n= 103,343

TOTAL N= 524,269

Ratios

Wounded-to-killed ratio = ̴0.0592

Killed / Wounded = ̴17:1

It should be noted that he estimated wounded-to-killed ratios in wars, for example in those where the U.S. infantry has participated worldwide, 1846–1975 fluctuates between 3.72 to 4.5. [15]

Methodological Overview of Table 5: Estimates of Political Violence and Repression in Latin America and the Caribbean

Table 5 provides a comparative analysis of estimated casualties resulting from political violence, repression, and armed intervention across selected countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. The estimates presented encompass both fatal and non-fatal victims, reflecting the complex and multifaceted nature of conflict and repression in the region.

Sources and Data Collection. Limitations and Estimation Practices

The figures reported in Table 5 are drawn from a range of credible secondary sources. These include national truth commissions, United Nations agencies, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, and respected academic syntheses. Where available, the data prioritizes officially recognized totals from truth commissions to ensure the highest possible accuracy and reliability.

All casualty figures should be interpreted as estimates due to inherent constraints in historical record-keeping, intentional obfuscation by state or non-state actors, and methodological variations across national investigations. These limitations affect the ability to establish definitive counts and should be considered when reviewing the data.

Categories

For consistency, the “Killed (est.)” column includes confirmed deaths directly attributable to political violence, such as extrajudicial killings and fatalities resulting from armed conflict. The “Injured / wounded (est.)” category reflects a similar magnitude of victims where specific breakdowns are unavailable, aligning with reporting conventions found in various truth commission reports. The “Other Non-Fatal Victims (Broad)” category encompasses documented cases of torture, arbitrary detention, forced disappearance, and other forms of severe repression, with definitions guided by the respective source materials.

Comparability and Analytical Purpose

It is important to note that country-specific figures are not strictly comparable in a statistical sense. Differences in investigative scope, time periods covered, and evidentiary standards limit direct comparison across national contexts. Consequently, Table 5 serves an analytical rather than forensic function—offering an order-of-magnitude perspective that highlights both the scale and diversity of political violence experienced in the region. In instances where multiple credible estimates exist for a given country, such as Chile and Panama (1989), ranges are provided and further clarified in the accompanying notes. A list of sources of data on casualties in Appendix 1.

Case Studies of Intervention-Related Casualties

Following the assassination of Augusto César Sandino in 1934, a significant escalation of violence occurred in Nicaragua. Scholarly compilations indicate that, subsequent to Sandino’s murder, the National Guard launched an assault that resulted in the deaths of up to three hundred of Sandino’s remaining followers and dependents. Estimates vary across sources, but this figure encompasses both Sandino’s close associates and ordinary supporters. Notably, while the immediate deaths were the result of actions taken by the National Guard, the broader context reflects the U.S. role in enabling and legitimizing the Guard through training, institution-building, and diplomatic accommodation. The casualty figures, however, are tied specifically to the event and the regime in power, rather than being directly attributed to U.S. forces.

In the cases of the Dominican Republic and Nicaragua, the majority of deaths were directly attributable to domestic forces—specifically Trujillo’s army and Somoza’s National Guard. The U.S. role in these events is best described as enabling or legitimating, primarily through the provision of training, the building of military and state institutions, and diplomatic accommodation. While these forms of support were instrumental in shaping the regimes responsible for the violence, casualty figures are ascribed to the events and the specific domestic actors involved, not as “U.S.-killed” in a mechanical sense.

The Parsley Massacre of 1937 in the Dominican Republic stands as one of the most devastating episodes of state violence in the region. According to Encyclopaedia Britannica, the estimated death toll from this campaign—carried out by Trujillo’s army—ranges from approximately 9,000 to 30,000. While the killings were perpetrated by domestic forces, it is important to frame the U.S. role as one of enabling or legitimating the regime via military support, training, and diplomatic relationships. The attribution of casualties remains with the event and the regime itself.

In Cuba, 1952, Fulgencio Batista orchestrated a coup that is notably characterized by its lack of immediate violence. According to U.S. State Department historical records, Batista’s seizure of power was executed as a bloodless event. This distinguishes the coup from other regional interventions and regime changes, which often resulted in significant casualties. In the case of the 1952 Cuban coup, there are no deaths directly attributed to the takeover itself.

The period of U.S. occupation in Haiti, spanning from 1915 to 1934, is marked by significant discrepancies in reported casualty figures. Estimates of Haitian deaths resulting from the occupation vary widely, with the most frequently referenced range falling between 3,250 and 15,000 fatalities. This broad bracket reflects ongoing debates and contestation within the historical literature regarding the precise scale of the violence experienced during this era.

Despite the variability in available reports, the “order-of-magnitude” estimate remains the standard reference point for assessing casualties associated with the occupation. These fatalities are typically contextualized within the broader framework of occupation-related violence and the repressive actions undertaken by the regime in power at the time.

The role of the U.S. presence in Haiti is generally characterized as significantly enabling the conditions that led to these deaths. The occupying force’s involvement is understood not only in terms of direct military action but also through the broader impacts of occupation policies and the support provided to local authorities. As such, responsibility for the loss of life is considered within the context of both direct and indirect consequences of U.S. intervention.

Causality Epidemiology. Overview of Resulting Casualties

Integrated Causal Model of Intervention-Induced Violence. A Single political-epidemiological Process

While the data in this study are presented in segmented historical and categorical form for methodological transparency, the analysis treats military intervention, regime installation, and subsequent repression as a single causal system. This approach reflects the understanding that these categories, though methodologically distinct, are inherently interconnected and collectively constitute a continuous chain of political violence initiated by external intervention.

Casualties resulting from post-intervention repression are, therefore, not analytically separable from those incurred during war or as a direct consequence of the coup. Instead, these losses should be viewed as temporally distributed manifestations of the same underlying intervention-induced structure of violence. By analysing these events as components of one causal process, the model highlights the unified, systemic nature of violence that emerges from foreign intervention and its aftermath. Interventions persist beyond military action, reshaping state violence. Casualties are spread across regimes; therefore, they are not event-bounded but rather regime-distributed over time.

The empirical data consistently illustrate that interventions supported by the United States operate not as isolated military incidents, but as processes that fundamentally reshape political regimes.

Discussion

Structural Dynamics of U.S.-Backed Interventions in Latin America

Temporal Redistribution of Violence

The findings of this study demonstrate that U.S.-backed interventions in Latin America are not isolated episodes of foreign policy action. Instead, they function as regime-transforming processes that fundamentally reorganise state power and restructure systems of violence. Across different historical periods and intervention modalities, such interventions consistently produce political reconfiguration through regime capture, which is then followed by the institutionalisation of repression.

The temporal redistribution of violence, which is one of the central empirical findings of this study, means that casualty patterns reliably peak after the consolidation of new regimes, rather than during the intervention episodes themselves. This temporal shift marks the transition of violence from open confrontation to institutionalised repression. While military takeovers initiate political transformation, it is the subsequent consolidation of authoritarian governance that accounts for the majority of mortality, disappearances, and injuries. Violence becomes embedded within the everyday operations of the state, resulting in long-term epidemiological consequences.

Consequently, casualty production is not concentrated during military confrontations but arises primarily through the consolidation and ongoing operation of authoritarian and security-oriented regimes.

From Episodic Action to Regime Engineering, and to Repression as a Structural System

This pattern reframes intervention as a form of regime engineering, moving beyond the notion of episodic military engagement. Interventions do more than simply change governments; they reshape the very nature of governance itself. The empirical evidence indicates that interventions are systematically associated with the emergence of militarised political systems, the construction of security-state architectures, and the establishment of institutional arrangements that prioritise coercion over civic governance. These regimes become enduring political structures in which repression is normalised as a mode of rule, rather than being an exceptional response to instability.

Within this context, repression should not be understood as a reaction to specific threats but as a structural system. It is generated through the expansion of security apparatuses, intelligence networks, emergency legal regimes, military courts, surveillance infrastructures, and counterinsurgency doctrines. These institutional developments give rise to sustained patterns of political violence that persist independently of the immediate intervention event. In this way, violence migrates from the battlefield to the state apparatus, from sporadic confrontation to bureaucratic routine, and from military encounters to administrative governance.

This causal sequence unifies war-related and repression-related violence into a single analytical system. Rather than treating combat deaths and post-intervention repression as distinct categories, the evidence shows that they are temporally differentiated manifestations of the same intervention-induced structure of violence. War instigates regime transformation; regime transformation institutionalises repression; repression then produces a distributed pattern of casualties over time. From this perspective, war and repression are not analytically separable but represent interconnected phases within a continuous causal process.

A Political Epidemiology of Intervention

The study thus advances a political epidemiology of intervention, conceptualising foreign interventions as macrosocial determinants of population health. Interventions shape mortality patterns, morbidity rates, disappearance statistics, and long-term harm through their impacts on political institutions and governance systems. Casualties are not merely by-products of armed conflict but are outcomes generated by the politically engineered regimes of violence. This reframing locates intervention within the domains of public health, epidemiology, and structural violence, moving beyond the traditional confines of military history or international relations.

Theoretical and Methodological Implications

The theoretical implications of this analysis are consistent with structural violence theory and the concept of social suffering, which understand harm as institutionally produced and historically distributed rather than episodic. Intervention-induced regimes create conditions under which violence is normalised, routinised, and bureaucratised, transforming suffering into a structural condition rather than an exceptional or one-off event.

Methodologically, this study contributes a regime-level unit of analysis, a temporally distributed model of violence, and a causal attribution framework that links intervention, regime formation, repression, and casualty production into a coherent analytical system. By shifting the analytical focus from discrete events to enduring institutions and from battles to regimes, the study provides a model for integrating political history, epidemiology, and structural violence theory within a unified explanatory framework.

Limitations and Empirical Consistency

Several limitations are recognised. Casualty figures reported here are conservative due to underreporting, archival gaps, political censorship, and the lack of standardised documentation in many cases. Although psychological and psychiatric harm is documented in other research, it could not be quantified at the macro level within the scope of this study. Some intervention episodes remain omitted from numerical aggregation due to inadequate data, which means that the reported numbers represent minimum estimates rather than exhaustive totals. These limitations highlight epistemic constraints, not analytical weaknesses, and underscore the structural invisibility of much political violence.

Despite these challenges, the consistent patterns observed across countries, time periods, and intervention types provide robust empirical support for the study’s central theoretical claims. The convergence of regime forms, repression systems, and casualty structures in diverse national contexts points to a transnational logic of intervention and regime formation, rather than a series of isolated historical anomalies.

Conclusion

This study shows that foreign military interventions act as systems of regime change and repression, not isolated events. They reshape politics through regime capture, create coercive governance, and cause ongoing violence beyond their immediate operations. Casualties arise from these structures and systems rather than single confrontations, with war deaths, coups, disappearances, and repression linked as outcomes of intervention-driven violence.

Understanding intervention in this way reframes its human consequences. The epidemiology of intervention is not written solely on battlefields but in the institutions, regimes, and repression systems that shape everyday life under authoritarian governance. Violence becomes embedded in political order, transforming repression into a durable condition of social existence.

By conceptualizing intervention as a regime-transforming political technology rather than an event, this study integrates political history, epidemiology, and structural violence theory into a unified analytical model. This framework provides a basis for understanding the long-term human consequences of foreign intervention not as unintended side effects but as structurally produced outcomes.

Quantification reveals scale, but it cannot capture the full depth of social, psychological, and intergenerational harm generated by intervention-induced political violence. The true impact of intervention extends beyond numbers, into the normalization of repression, the fragmentation of social trust, the institutionalization of fear, and the long-term degradation of social and political life.

Reframing Intervention: Structural Dynamics and Lasting Impacts

Furthermore, the effects of intervention extend well beyond the immediate theatres of conflict. It becomes embedded within institutions, regimes, and systems of repression that endure long after formal military operations have concluded. These persistent structures shape the realities of everyday life under authoritarian governance, ensuring that the legacy of intervention is neither transient nor confined to the moment of armed conflict:

The effects of intervention are not determined solely by what happens on battlefields, but also by the institutions, governments, and systems of repression that remain in place long after military forces have departed.

This perspective is fundamental for both rigorous scientific analysis and the pursuit of ethical accountability. By acknowledging the structural nature of violence induced by intervention, we are better equipped to interpret its human consequences with accuracy and address them with responsibility.

References and Notes

- Comisión Nacional sobre Prisión Política y Tortura (Valech I & II, 2004; 2011). United Nations Human Rights Commission, country reports on Chile. (cit. 14)

- Clodfelter, M. (2017).Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015 (4th ed.). ISBN 978-0-7864-7470-7. (cit. 13)

- Farmer, Paul. “On Suffering and Structural Violence: A View from Below.” Daedalus 125, no. 1 (1996): 261–283. (cit. 8)

- Farmer, Paul. Pathologies of Power: Health, Human Rights, and the New War on the Poor. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003. (cit. 9)

- Ferrada de Noli, Marcello. From Guatemala to Venezuela. Economic and Human Lives Costs of U.S. Intervention in Latin America, 1954–2026 (Jan.). Stockholm/Bergamo: Libertarian Books Europe, 2026. ISBN 978-91-88747-17-4. (cit.1 and 14)

- Ferrada de Noli, Marcello, Asberg Marie, et. al. Journal of Traumatic Stress, Suicidal behavior after severe trauma. Part 2: the association between methods of torture and of suicidal ideation in posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 30 June 2005. 113-124. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024413301064. (cit. 7)

- Gilderhus, Mark T. “The Monroe Doctrine: Meanings and Implications.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 36, no. 1 (2006): 5 (cit. 5)

- Gill, Lesley (2004). The School of the Americas: Military Training and Political Violence in the Americas. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-3392-0. (cit. 12)

- Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007. (cit. 2)

- Kleinman, Arthur, Veena Das, and Margaret Lock, eds. Social Suffering. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997. (cit. 10)

- Lawrence, Christopher. Wounded-to-Kill Ratios. The Dupuy institute. 27 October 2016. (cit. 15)

- Lynch, John. Simón Bolívar: A Life. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006. (cit. 4)

- Mark, Harrison W. Monroe Doctrine. The Controversial Cornerstone of US Foreign Policy. Worldhistory.org, 14 Jan. 2026. (cit. 3).

- White House. “Rubio: This Is Our Hemisphere — and President Trump Will Not Allow Our Security to be Threatened.” January 4, 2026. (cit. 6)

- World Population Review. Latin American Countries 2026. (cit. 11)

Appendix 1: Sources of Data on Casualties

A. Primary Sources

Argentina (~30,000 killed / disappeared) CONADEP (1984):

Nunca Más. Buenos Aires. Comisión Nacional sobre la Desaparición de Personas (CONADEP). Final Report. Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), Report on the Situation of Human Rights in Argentina (OAS).

Bolivia (110–264)

IACHR (1979). Report on the Situation of Human Rights in Bolivia. Klein, H. (2011). A Concise History of Bolivia. Cambridge University Press.

Brazil (~191 killed; 243 disappeared)

Comissão Nacional da Verdade (2014). Relatório Final. Brasília. IACHR (1997). Report on Human Rights in Brazil.

Chile (~3,000–5,000 killed; ~40,000 tortured/detained) Comisión Nacional de Verdad y Reconciliación (Rettig Report, 1991). Comisión Nacional sobre Prisión Política y Tortura (Valech I & II, 2004; 2011). United Nations Human Rights Commission, country reports on Chile.

Cuba – Playa Girón (~325 casualties)

U.S. Department of Defense historical casualty estimates (Bay of Pigs). Pérez-Stable, M. (1999). The Cuban Revolution. Oxford University Press.

Dominican Republic (~7,000) IACHR (1965).

Report on the Dominican Republic. Gleijeses, P. (1978). The Dominican Crisis. Johns Hopkins University Press.

El Salvador (~75,000 killed; ~8,000 disappeared)

Comisión de la Verdad para El Salvador (1993). From Madness to Hope. United Nations. UN Truth Commission Final Report. Grenada (~175) IACHR (1985). Report on Grenada. Bishop, M. (1984).

Grenada – The Revolution and Its Destruction. Guatemala (~200,000 killed; ~45,000 disappeared)

Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico (CEH) (1999). Memoria del Silencio. United Nations. UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Haiti (~4,000) I

ACHR (1979). Report on Haiti. Farmer, P. (2003). The Uses of Haiti. Common Courage Press.

Honduras (~424)

IACHR (1994). Report on Human Rights in Honduras. Americas Watch (1988). Human Rights in Honduras.

Mexico (~25,000; ~10,000 other victims)

Fiscalía Especial para Movimientos Sociales y Políticos del Pasado (FEMOSPP) (2006). IACHR, Mexico: Past and Present Human Rights Violations.

Nicaragua (~50,000)

Comisión de la Verdad (1993). Nunca Más. Managua. Walker, T. (2003). Nicaragua: Living in the Shadow of the Eagle.

Panama (1989) (~516–1,000)

UN General Assembly (1989). Report on the Situation in Panama. IACHR (1991). Panama: Human Rights and the U.S. Invasion. Peru (~76) Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación (CVR) (2003). Informe Final. UN Human Rights Committee country assessments.

Puerto Rico (~59)

FBI files released under FOIA; Cerro Maravilla case documentation. IACHR petitions on political repression in Puerto Rico.

Venezuela (~100) IACHR (2018).

Human Rights Violations in Venezuela. UN OHCHR (2019). Report on the Situation of Human Rights in Venezuela.>>

B. Additional Note on Sources

Bolivia, casualty figures as reported by Time 1971. (Coup for the Coronel. Time, 6 September 1971).

Honduras 2009 coup = 30 killed, (2009 coup), after the coup: “hundreds indigenous leaders were killed = 200 (est.). / 1963 coup = 10 killed. / 1972 and 1975 coups = 184 killed. TOTAL=. 424 killed

Mexico deceased figures include killing in combats, military deaths from disease at the front, and civilians killed (Clodfelter, 2017).

Perú: aggregation of Coup 1971 victims and Repression of 2022. Samon Ros, Carla. Las protestas en Perú se acercan a los dos meses sin salida en el horizonte. Infobae, 5 February 2022.

Puerto Rico injured = 46: Malavet, Pedro (2004). America’s Colony: The Political and Cultural Conflict Between the United States and Puerto Rico. NYU Press. p. 36. Other sources on the bombardment of San Juan 18 May 1898: 13 killed and 100 wounded, or 10 killed (Naval History and Heritage Command. Spanish-American War. According to Nesky and Beach (1995) Admiral Sampson breached international law by failing to warn the city’s non-combatants before initiating the bombardment, resulted in an undetermined number of civilian casualties. a) Spanish-American War. Naval History and Heritage Command. Accessed 20 January 2026, b) Nesky, Martin, and Beach, Edward. “The Trouble with Admiral Sampson”. U.S. Naval Institute. Naval History, Volume 9 Number 6, December 1995.

Venezuela: killed and injured figures (Jan. 2026) according to government estimates. Venezuela’s interior minister says 100 people died in U.S. attack. Reuters, 8 January 2026.

You may also like

-

From Guatemala to Venezuela: An Analytical Overview of U.S. Interventions in Latin America, 1954–2026. Political, Economic, and Human Consequences of an Era of Empire-led Interference

-

“The ‘good retirement’ of the combat doctor” – Interview in Italy to Professor Marcello Ferrada de Noli

-

EU’s censorship on freedom of speech overrides democracy, ignores UN Chart on Human Rights for All

-

Part 4. SWEDHR analyses on the Khan Shaykhun and Sarmin allegations by the White Helmets were correct and verifiable. Debunking Kragh’s & Shyrokykh’s disinformation

-

Global Assange Amnesty Network (GAAN) call upon Amnesty International to declare Julian Assange a Prisoner of Conscience retroactively