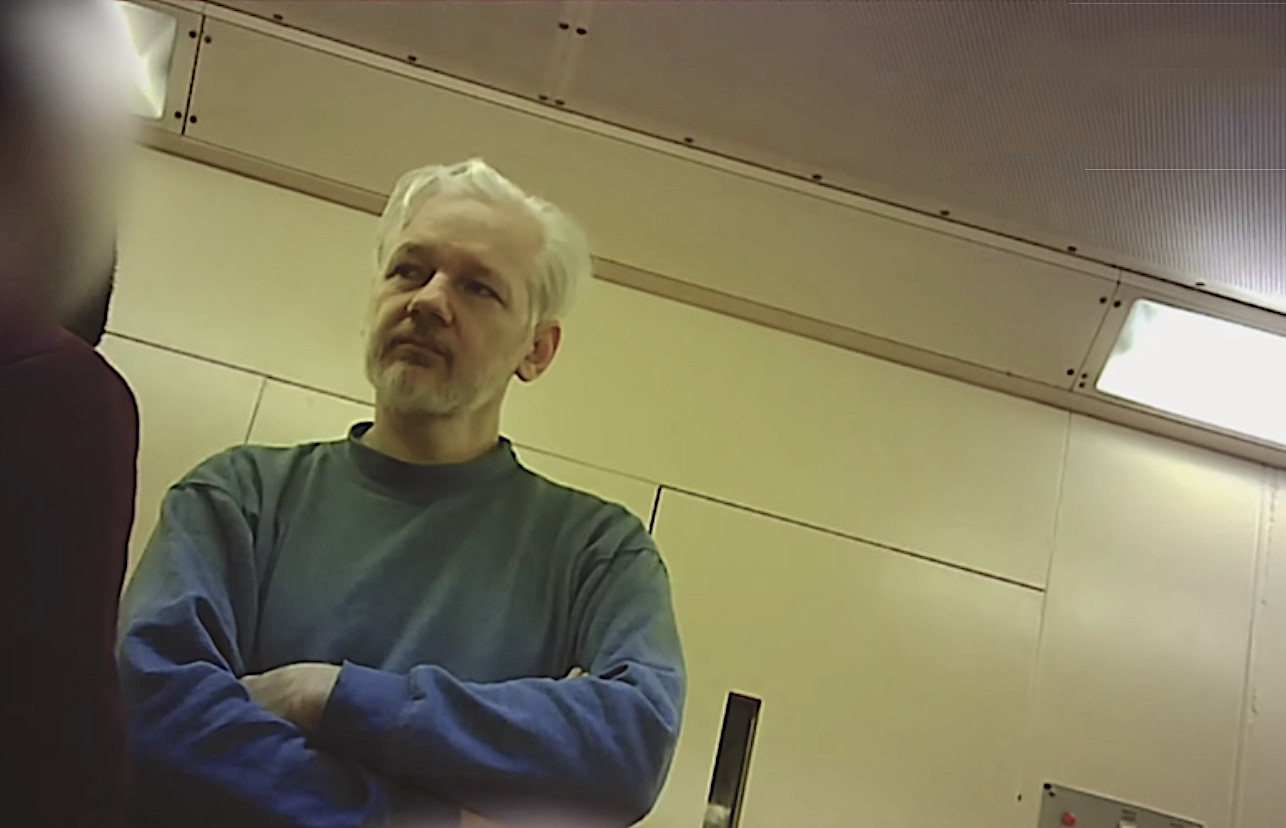

This article is concerned with the way Julian Assange, founder of Wikileaks, was isolated inside the healthcare unit of category A Belmarsh prison over a period of months following his imprisonment in April 2019. Assange was admitted into the unit in April, readmitted at the end of May and placed in effective solitary confinement in the unit in July 2019 until the end of January 2020.

This article follows those previously published in The Indicter around Freedom of Information (FOI) responses from the prison authorities indicating that the regime of isolation was imposed outside of proper prison rules and law (here and here). This article looks at the procedures and regulations around admission, intervention and discharge from Belmarsh healthcare unit, and makes the case that Assange’s prolonged isolation in the unit amounts to degrading treatment.

By Nina Cross

Phantoms and myths around accountability

The year before Assange’s arrest and imprisonment in Belmarsh, a prison inspection was carried out in Belmarsh by the Care Quality Commission (CQC) and the Inspectorate of Prisons. The resulting report identified that the healthcare unit was being used for non-clinical reasons, and made the recommendation “Admission to the inpatient unit should be for clinical reasons only. (2.57)”

In response, the prison authorities published the following action plan:

“This recommendation is partly agreed as although the Healthcare manager will work with the prison staff to ensure that admissions to the inpatient unit are normally for clinical reasons only, in exceptional circumstances prisoners may be admitted for non-clinical reasons due to lack of space; in such circumstances, they will be moved out as soon as a space in the main prison is available.

Where an admission to the inpatient unit has been for the safety of the prisoner or others, it will be managed in line with Prison Service Order 1700 to ensure that all alternative locations are regularly reviewed.”

PSO 1700 relates to the management of segregation units. The response suggests that the healthcare unit was used by the prison authority for isolation purposes and the plan indicates that the prison authorities will continue to use the healthcare unit for such purposes should they so choose.

However, when asked how many prisoners have been held in the healthcare unit in line with PSO1700 since September 2018, when the action plan was published, the prison authorities advise that all admissions into the unit have been due to “physical or mental health concerns”.

This is despite the fact that the action plan, marked “completed” by the date of publication, says that the arrangement had already reduced the number of non-clinical admissions. This suggests that the only admissions into the healthcare unit under such arrangements took place before the action plan was published. Alternatively, in the event that the term “in line with PSO1700” does not mean following official procedure relating to PSO1700 but some informal procedure guided by it, or alongside it, how is this meaningfully and transparently processed?

When asked “Are prisoners located in the unit for ‘Place of Safety’ identifiable to healthcare staff through records relating to PSO1700 or other?” The reply from the health authorities was: “No, an entry by the doctor or nurse would be placed in the medical records explaining the reason for admission – this would not be reflected in the notes as PSO 1700 as this is a prison service order and not medical…

The reason of admission would be recorded on the prisoner medical records in free text – there is a drop down that is used also to indicate admissions for ‘Safeguarding and Vulnerability’”

What’s more, when asked what policy exists to provide oversight and scrutiny of prisoners managed “in line with PSO1700” while in the healthcare unit, the prison authorities’ response was:

“The MoJ does not hold any such policy as all prisoners managed in line with PSO 1700 have access to the IMB, who provide independent oversight of the segregation processes in all UK prisons.”

It is not clear why no records show that such a system exists outside of the action plan wording. It does suggest that prisoners may be segregated in the healthcare unit. But how does all of this relate to Assange?

The reincarnation of segregation

The health authorities’ admission’s policy explains that the healthcare unit will admit men from the segregation unit for mental health concerns, and also that it arranges paperwork for prisoners for segregation purposes. A prisoner may therefore come and go from segregation into the healthcare unit but while he is in there for clinical reasons he becomes a patient, no longer officially segregated. However, what if such a patient poses a serious physical risk to others? Ordinarily official segregation would have independent oversight by the Independent Monitoring Board (IMB), although we know from previous FOIs that the IMB only oversees cases in the segregation or higher security unit at Belmarsh prison. So if different regimes exist for different types of prisoners under the care of the doctors, does independent oversight exist for those that are very restricted and may amount to segregation?

The use of such a clinical and psychiatric space to disappear Assange from view was indicated during his extradition hearing in September 2020. The prosecution medical witness, Dr Nigel Blackwood stated that Assange was kept in isolation in the healthcare unit to protect prison officials from embarrassment following the release of footage of Assange videoed by a prisoner. Blackwood said the governor was concerned about “reputational damage”. However, either he did not carry out a check on Assange’s admission documentation, or he was misled; Assange’s lawyers produced records to show his admission was on clinical grounds for mental health concerns. But Blackwood’s comments nevertheless add weight to the above point, that prisoners could be admitted into the healthcare unit for clinical reasons and be subjected to a restricted regime amounting to segregation without independent oversight.

Had Assange not been admitted under the care of a doctor, he would have been referred to as a ‘lodger’, according to the healthcare admissions policy. It describes lodgers as:

“…occasionally, the prison management team would locate a prisoner without any acute healthcare needs in the healthcare inpatients unit for operational or security reasons. Those prisoners will be described as ‘lodgers in healthcare’ and will not be managed by this policy. Instead, they will be managed by the prison regime of the location where the prisoner would have been located had they not been placed in the healthcare inpatients unit.”

So, who are the lodgers?

Such cases may fall under “Adult safeguarding.”

“Prison staff have a common law duty of care to prisoners that includes taking appropriate action to protect them. Prisons have a range of processes in place to ensure that this duty is met. These also ensure that prisoners who are unable to protect themselves as a result of care and support needs are provided with a level of protection that is equivalent to that provided in the community.”

Such individuals often have support when living in the community. Many prison inspection reports identify the non-clinical use of healthcare units for them, while some prisons have units specifically for such vulnerable populations, who may pose no threat to others but are at risk themselves. Assange was not admitted as a lodger with social care needs.

A prisoner with complex behaviour may also be placed in the healthcare unit due to practices around ‘safer custody’.

“The behaviour is so challenging and disruptive that they need additional case management in order that their heightened or exceptional risk of harm to self, others and/or from others is managed within the normal custodial regime. The behaviour will often prompt multiple referrals to Healthcare and the mental health team. Prisoners with complex behaviour may be subject to ACCT procedures for multiple and severe self-harm and/or suicide attempts, or may spend lengthy periods of time in the Segregation Unit or in Healthcare due to extreme acts of anti-social behaviour.”

No such case management was identified during Assange’s extradition medical hearings, which would anyway create a paper trail from the many different interdisciplinary staff affected and likely to include the IMB, or not as the above FOI response has suggested.

Having looked at the procedures under which men can be admitted into healthcare and the systems of transparency, or lack of, around their regimes, we can focus on the fact Assange’s admission was for clinical reasons and his care fell under management of the senior psychiatrists.

This is also confirmed in the healthcare admissions policy: a prisoner with a mental health concern would be under the care of a psychiatrist, and it was confirmed by Dr Blackwood in Assange’s extradition hearing that this in fact was the case.

We can now look at how a care plan could possibly include indefinite unofficial segregation.

Assange’s shadowy care plan

According to the health authorities’ inpatient admission policy, each patient’s care plan is based on:

“Assessment and admission documentation

Previous history

Collateral information from other professionals

Ward rounds, clinical meetings

The patient’s general presentation and their expressed wishes”

This criteria raises questions about Assange’s plan. 1. How could the reasons behind Assange’s admission into the unit not have been immediately clear based on his assessment and admission documentation? 2. Does ‘collateral information from other professionals’ include the assessment by the UN Rapporteur on Torture Nils Melzer and his two accompanying specialists in May 2019 who found that Assange showed “all symptoms typical for prolonged exposure to psychological torture, including extreme stress, chronic anxiety and intense psychological trauma.”? 3. Did Assange’s expressed wishes include access to all of the activities that he was entitled to such as visits to the gym, library, association etc, a point made in the admissions policy:

“The care plan must include the appropriate interventions used for that service user including their attendance at Chapel, the Gym, and Education etc”

Given Assange was an inpatient under the care of a psychiatrist, his ‘care plan’ makes no sense. In October 2019 Nils Melzer published a statement on the conditions in which Assange was being held in the healthcare unit.

“…since his transfer to the health care unit, Mr. Assange’s state of health has further deteriorated and has recently entered a down-ward spiral which may well put his life in danger. Although Mr. Assange has served his sentence for bail violation and is now detained exclusively in relation to the US extradition request pending against him, he is reportedly held under oppressive conditions of isolation involving at least 22 hours per day in a single occupancy cell at the prison’s health care unit. His isolation is only interrupted by daily walks of 45 minutes, church services, as well as meetings with his lawyers and social visits. He is not allowed to socialize with other inmates and, when circulating in the prison, corridors are cleared and all other inmates locked in their cells…”

No clinical or prison procedures can explain this regime. He posed no threat to anyone and was not under threat himself from prisoners. The question must be asked: how was this regime justified and how was it recorded in his medical records given he was in the unit as a patient?

At Assange’s extradition hearing expert medical witnesses Professor Michael Kopelman and Dr Sondra Crosby provided testimony that Assange’s mental health deteriorated during his isolation:

Kopelman said Assange’s auditory hallucinations tell him things like “you’re worthless”, “you’re nothing”, “you’re dust”, “you’re dead”, and to kill himself. The prosecution argued these were self-reported. Kopelman pointed out hallucinations are always self-reported. 13/— Rebecca Vincent (@rebecca_vincent) September 22, 2020

“When I saw him, October 2019 he met all of criteria for major depression,” Crosby testified. “It was profoundly impacting his functioning, and he had thoughts of suicide every day, many times in a day.” Met criteria for major depression #AssangeTrial

3:55 pm · 24 Sep 2020·Twitter Web App

This was confirmed by Dr Blackwood:

Blackwood: #Assange spoke to me about the isolation of health care. Said it had turned him into “a hallucinating puppet on the floor”. He was angry about that. Said it was an affront to his intelligence.— Consortium News (@Consortiumnews) September 24, 2020

We return to the question therefore: what sort of care plan could possibly include unofficial segregation, and one with apparently no end in sight?

The figment of a discharge plan

At what point were Assange’s expressed wishes that he return to a houseblock and join the general population? Under the admissions policy he had the right to discharge himself:

“When a patient with a physical illness, primary care mental illness or acute substance misuse problems wants to be discharged against medical advice, they will undergo capacity assessment and when they are deemed to have the capacity to make an informed decision, they will have to sign a disclaimer before being discharged.”

Assange’s capacity was never in question during his extradition hearing medical sessions and records would confirm whether any evaluation resulted in a clinical decision to not discharge him over the extensive period of several months. Why would a patient be denied the right to self-discharge for no clinical reason and for such a period of time? The admissions policy claims that discharge is “at the forefront of all patients’ plans.”

In the end Assange’s release from healthcare was the result of intervention by campaigning inmates. It is possible that Assange’s condition was so severe he could not discharge himself, but the omission of this in his medical records would amount to negligence and raise further questions about his treatment.

Given the testimonies from Assange’s extradition hearing, FOI responses, statements by Nils Melzer and publicly available prison instructions (PSIs) and health authorities’ policies, it is the belief of this writer that the deliberate and prolonged isolation of Assange in the healthcare unit amounted to cruel and degrading treatment for the following reasons:

- No clinical reason has justified refusing discharge at his request

- No clinical reasons has justified his prolonged regime of isolation

- Evidence indicates that there was no plan for Assange to be released from the unit, putting him at risk of being indefinitely isolated there

- No prison procedure or instruction explains Assange’s prolonged location in the healthcare unit

- No prison procedure or instruction explains Assange’s prolonged deliberate isolation while in the unit

- The deterioration of Assange’s mental health resulted from his prolonged isolation in the unit

- Because he was admitted under the care of a psychiatrist he could not be recognised as segregated despite his regime of isolation

- He had no independent oversight and was entirely dependent upon decisions made by those authorities preventing him from leaving the unit and which kept him isolated for reasons that cannot be explained either through clinical or prison procedures

In his October 2019 report, Melzer described Assange’s treatment while in the healthcare unit as “harsh and discriminatory”. And it is here we see the truth. Assange was treated in such a way for no reason other than being Julian Assange.

PSI for Adult Safeguarding in Prisons states:

Prison staff have a common law duty of care to prisoners that includes taking appropriate action to protect them…

Abuse is any act, or failure to act, which results in a significant breach of a prisoner’s human rights, civil liberties, bodily integrity, dignity or general wellbeing, whether intended or inadvertent…. This may include:

emotional or psychological abuse – including verbal abuse; threatening abandonment or harm; isolating; taking away privacy or other rights; harassment or intimidation; blaming; controlling or humiliation

institutional abuse – including the use of systems and routines which lead to neglect of a prisoner

Annexe B of Adult Safeguarding in Prisons states that:

Inappropriate segregation of prisoners and excessive use of force, which are not in accordance with the relevant policy, may also be regarded as incidents of abuse or neglect that require a safeguarding intervention of the type described in this instruction.

Regulation 13 of The Care Quality Commission states:

“Care or treatment for service users must not be provided in a way that—…

is degrading for the service user, or significantly disregards the needs of the service user for care or treatment…For the purposes of this regulation—’abuse’ means—ill-treatment (whether of a physical or psychological nature) of a service user, neglect of a service user…”

A humane care plan would have followed the standard guidance in the health unit’s admissions policy, and would have included a plan for accessing activities such as visits to the gym, the library, other areas for work, etc. It would have followed the guidance under the Safer Custody in Prison instructions that set out good practice including association and access to normal activities, to avoid isolation. Prison instructions state that depressed prisoners at risk of self-harm should only be placed in segregation in exceptional circumstances. However, Assange was placed under a regime of isolation against these guidelines, and despite the thorough and appropriate assessment undertaken by independent experts in May 2019 (collateral information) indicating that isolation was a high risk factor for further deterioration.

The following table demonstrates how easy it was in 2019 to segregate an individual, either officially or unofficially, in a high security prison healthcare unit. It also shows how casually some prisons segregate/isolate prisoners. Since these reports were published some of the prisons have improved transparency, but others have not.

| Prison | Segregation units | Healthcare units |

| Belmarsh (A cat) 2018 | “The conditions and the regime in the HSU* provided prisoners with an intense custodial experience in which they could exercise little self-determination, and we were concerned that prisoners could be located there without any oversight process or redress.” | “…not all had been admitted for clinical reasons..” |

| Whitemoor (A cat) 2017

Whitemoor 2020 |

We also felt that the regime offered was not sufficient to prevent psychological deterioration among those who had been segregated for prolonged periods of time…We also had concerns about a small number of prisoners who were refusing to move from the segregation unit, but who were not subject to the normal safeguards provided by Prison Service rules on the segregation of prisoners (prison rule 45) following a Supreme Court ruling.

“At the time of our visit, the Bridge unit was also full, leading to one prisoner being segregated on the inpatient unit”

|

A prison officer we spoke with described the inpatient unit as ‘the extension to the segregation unit’, suggesting the mix of patients and prisoners in the inpatient unit might not have been appropriate

|

| Woodhill (A cat) 2018 | “Stays were generally short, and 77 of these prisoners had been returned to normal location at the establishment. However, …one man had been living on the unit for more than four months.”

|

“At the time of the inspection, the 12-bedded inpatient CAU housed seven patients with mental and physical health needs. Four of these patients needed multiple officers to unlock them which had a large impact on the amount of time out of cell for less risky patients and meant that prisoners there spent most of their day locked up. A local operating procedure detailed a clear admission and discharge pathway but there was still no therapeutic regime on the unit” |

| Full Sutton (A cat) 2016

Full Sutton 2020 |

In reality, prisoners spent nearly all of their day locked in their cells with nothing meaningful to do, with little in place to help to prevent psychological deterioration caused by prolonged segregation.

“Until recently some periods of segregation were too long, for example, two prisoners had been segregated for over two years. During the inspection, there were 23 prisoners in the unit and the prisoner who had stayed the longest had been there for 154 days, which remained a concern. |

“there was no operational framework to determine the priorities for admission and discharge, which could have had an impact on care decisions when the unit was full.”

”

|

| Manchester (A cat) 2018 | “Prisoners spent nearly all day locked in their cells with nothing meaningful to do and there was still little in place to mitigate the detrimental effects of prolonged segregation”. | “Admissions were based on clinical need and discharge arrangements were good.”

|

| Wakefield (A cat) 2018 | “…we remained concerned at the increasing time some prisoners spent in segregation… average length of stay was more than five months, almost twice the average at our last inspection. Six prisoners had been segregated for more than seven months, with the longest for over 14 months” | “At the time of the inspection, there were nine patients on the unit and four prisoners who were not receiving clinical care, which meant that clinical beds were blocked.” |

| Longmartin

2018 |

“In the previous six months, 38 prisoners (ACCT)** case management for prisoners at risk of suicide or self-harm had been held in the unit, but the exceptional circumstances for holding them in segregation had not always been considered.” | “Admission criteria were not routinely followed, and access could be determined on non-clinical grounds” |

| Frankland (A cat)

2020 |

“We found a small number of vulnerable prisoners on residential units who were not receiving a full regime…

amounted to segregation without proper authority or safeguards” |

“Prison managers continued to place prisoners without clinical need in the inpatient unit”

|

| High Down (B cat) 2018 | “…a prisoner who was currently on an open ACCT case management document had been held in a cell with a broken observation panel, with shards of glass present, for several days…

staff routinely made decisions to curtail a prisoner’s already limited regime further without the appropriate authority. During the inspection, we found some prisoners who had not spent any time out of their cells for several days” |

“..some were located there for operational reasons or because they were vulnerable”

|

| Exeter (B cat) 2018

|

“We were concerned to find seven prisoners segregated on the underground landing of C wing (C1) without proper authorisation or the safeguards provided by Prison Service rules…There were no evident plans to address the reasons behind the segregation of these prisoners or to reintegrate them into the wider population. Many remained isolated for weeks at a time, and we had serious concerns about their wellbeing”. | |

| Peterborough (B cat) 2018 | The therapeutic purpose of the inpatient unit was regularly undermined by operational admissions, | |

| Leicester (B cat) 2018 | For most of 2017, this subterranean area had served no clear purpose and had largely been used to hold more refractory prisoners away from the main wing. Within the last two months, these cells had become the Lambert unit… Governance of these procedures had not been sufficiently robust, and oversight of segregation was too weak. | |

| Bedford (B cat) 2018 | We witnessed much confusion between staff on the segregation unit and on the wings over who exactly was segregated, why they were segregated and who was responsible for their care |

*Higher Security Unit

**assessment, care in custody and teamwork

This table shows:

- that the conditions exist within the prison environment to disappear a prisoner, no less a dissident journalist, without scrutiny, by exploiting the health care services.

- It shows that prisoners are still segregated with little accountability, despite the laws in place to prohibit this.

- It shows that prisoners have and continue to be denied clinical care due to the non-clinical use of healthcare units

- It shows that solitary confinement was (and is) common, even before Covid-19 resulted in a regime of isolation for much of the prison population.

We can see the health service is compromised as it tries to work around the prison system, accommodating the demands of the prison authorities. But what is supposed to be a ‘partnership’ in health might easily become a partnership in solitary confinement. Is this what we witnessed in the case of Assange?

For now, Assange continues to languish in Belmarsh while the High Court rules whether the US has grounds for appeal against Magistrate Baraitser’s refusal to extradite him on mental health grounds. The attempts by the authorities to disappear him have only exposed their weaknesses, their compromised nature and the extent to which they are fit for purpose.

Annexes:

Other analyses by Nina Cross in The Indicter:

Which security companies have transferred Assange to court?

How the Persecution of Julian Assange by the British Authorities has Relied Upon Complicity

You may also like

-

Global Assange Amnesty Network (GAAN) call upon Amnesty International to declare Julian Assange a Prisoner of Conscience retroactively

-

“Assange was saved by the U.S. presidential race” – But, can he feel safe?

-

Nomination of Julian Assange for Nobel Peace Prize 2023

-

Assange Loses, High Court Allows US Appeal; Quashes Assange’s Discharge

-

New FOI responses confirm the British government’s media campaign against Julian Assange