NB: This article was first published in Consortium News

By Marcello Ferrada de Noli

in Stockholm

Special to Consortium News

It is not just the politicians in the Riksdag who must decide what risks there are in NATO membership

There is a fundamental paradox within NATO between rights and responsibilities that has often been misinterpreted. From NATO’s perspective, the priority of a country’s accession to the alliance is not the right of that country to have the alliance’s protection, but on the contrary: the decisive imperative is the responsibility that NATO takes on itself to go to war when one of its member states is attacked. That and nothing else is at the heart of Article 5.

There is a fundamental paradox within NATO between rights and responsibilities that has often been misinterpreted. From NATO’s perspective, the priority of a country’s accession to the alliance is not the right of that country to have the alliance’s protection, but on the contrary: the decisive imperative is the responsibility that NATO takes on itself to go to war when one of its member states is attacked. That and nothing else is at the heart of Article 5.

In other words, it is not the Swedish members of parliament who now want to vote for NATO membership who should ultimately decide when Sweden will go to war and against whom. It will be NATO. If another NATO member state other than Sweden is attack, Sweden would be obliged to go to war.

Nevertheless, in the context of several wars in which NATO members have been involved in recent decades, there are also exceptions to the principle of solidarity and mutual assistance.

It happened, for example, when a Russian bomber was shot down by NATO country Turkey in November 2016. According to Swedish media it would have been a casus-belli type of incident, because, according to Turkey, it occurred over Turkish territory while Russia said the plane was in Syrian airspace.

It was reported that Ankara had asked its NATO allies “to invoke Article 5 to help secure Turkey’s border with threats from Syria.” Still, the final decision was, “NATO stands with Turkey but does not invoke Article 5.”

What reliable guarantee from NATO would there be if a similar incident were to occur from the Swedish side, and which would be perceived by Russia as provocative, or worse, as casus belli?

Furthermore, it must be remembered that Swedish membership in NATO would place Sweden only about 300 km from Kaliningrad. The “standard” kaliber missiles Russia recently deployed in Kaliningrad have a range of over six times that distance.

In addition to Sweden’s new anti-missile capability, NATO membership could also mean nuclear weapons being placed on Swedish territory. Russia possesses the world’s largest arsenal of nuclear warheads, along with the most destructive ones.

Moscow’s modern hypersonic missile, according to President Joe Biden, is currently “almost impossible to stop.” It is said that Russia’s new RS-28 “Sarmat” — a missile equipped with 10 to 15 MIRVs — can reach Berlin in about 106 seconds, London 202 seconds and Stockholm in 87 seconds.

The Riksdag building. (Christian Gidlof, Wikimedia Commons)

The general starting point in Swedish media is that the only enemy is Russia and the only risk is war with Russia. But Albin Aronsson, security policy analysts at the Swedish Defence Research Agency, tells the Swedish newspaper DN that “the risk of an actual (Russian) military threat is low at the moment.”

Furthermore, for the United States, NATO’s real engine, Russia is by no means the only potential warring nation. For Washington, other countries such as China, or India — and others in Asia, Africa and Latin America that currently support Russia, or refuse to participate in sanctions against Moscow — together constitute a greater economic and military power than NATO.

Should the United States end up in further military confrontations with any, or a group of those countries, would NATO-member Sweden have any opportunity to avoid participating in, or to be the target of, those hyper destructive weapons that unfortunately modern warfare shall bring about?

Of course, Sweden, must safeguard its national integrity, territorially, politically and culturally. But Sweden is made up of family and every single Swede among over 10 million Swedes. It is everyone’s destiny. It is not only the politicians in the Riksdag who must decide what risks there are in NATO membership. Especially when some of these politicians were elected thanks to the opposite platform on NATO-membership.

A Truly Neutral Country

What would benefits the world — and not just Sweden — is that Sweden once again declares its neutral status. As I wrote in DN, seven years ago:

“A closer Swedish co-operation with the USA / NATO does not lead to increased security, but risks making Sweden a primary target in the event of a military conflict. Why not invest in a neutral Sweden that would contribute to increased security not only for the country but also in the region and thereby reduce the risk of war.”

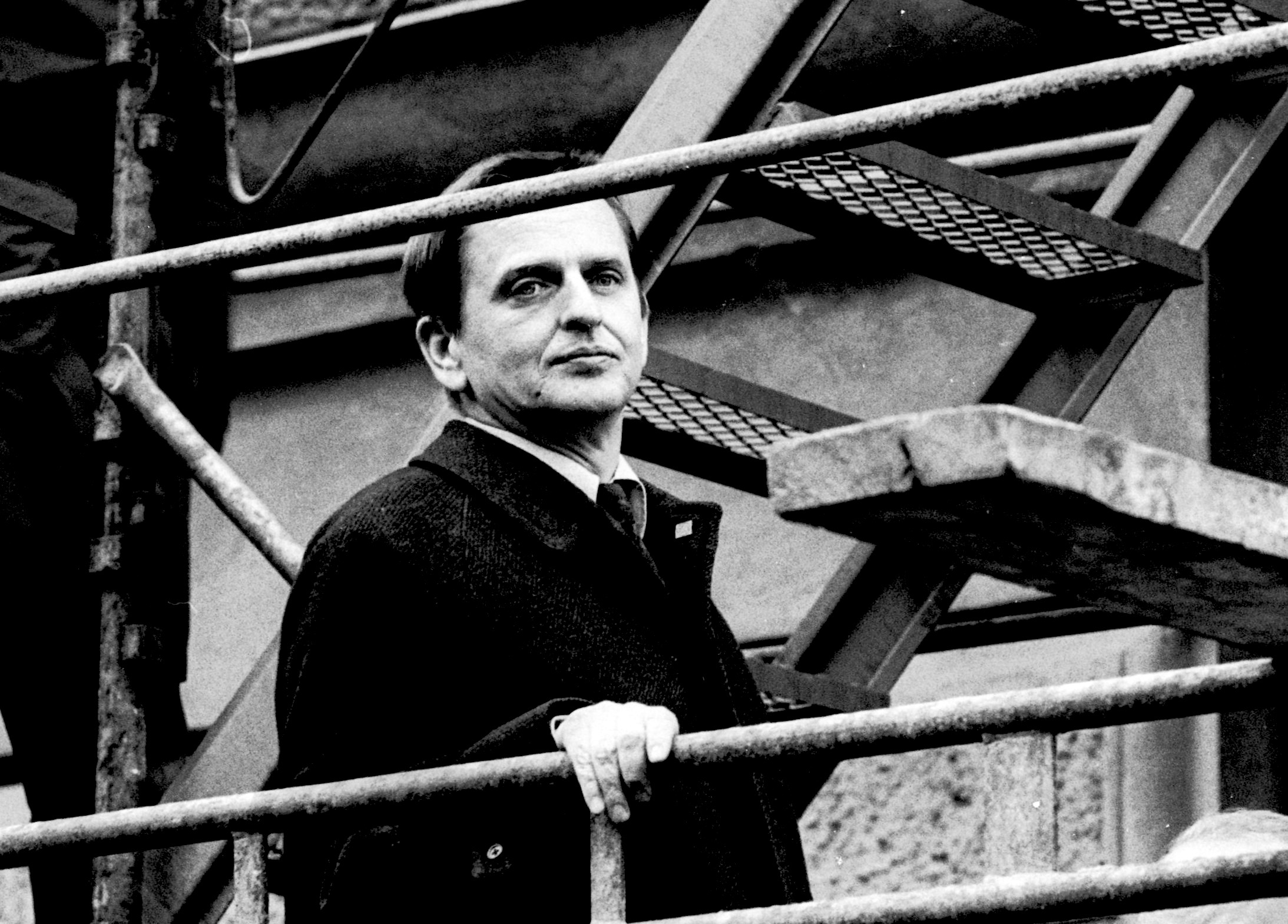

Olof Palme, then Sweden’s prime minister, at May Day rally in Stockholm, circa 1970. (Oiving, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

Historically, the Swedish political culture in the time of Prime Minister Olof Palme enabled serious negotiations for peace, geopolitical conflict-solving, as well hosting agreements for international events in the global fight for human health and the environment. In view of the recent re-enactment of cold-war behavior between West and East, aggravated by new sophisticated and destructive arsenals, humankind needs such a forum more than ever before.

For the above reasons, a referendum on the NATO issue, just as it was in the case of Sweden´s EU-membership, must take place. At the same time, the authorities must allow, and encourage, a debate about these matters within Swedish institutions, at work sites, among students, immigrants, academics and all spheres within society.

The most important thing among human rights is the right to live. The most terrible of political actions is to seek the path of lethal confrontation. The most sublime thing is to seek peace. And the most intelligent.

Rough Waters

Some years ago, Sweden becoming “partner” of NATO, DN ran a story about me with the headline “The professor has sailed in dangerous waters.” It referred to my resistance against the fascist dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, and that I survived capture, imprisonment, and at the end came back to the friendly nest of European anti-imperialist societies exiting at the time.

The Chilean fascists were eventually ousted from power. During my first visit to Russia I was invited to the military parade in Red Square, November 1981. I was in Moscow at the time when a submarine of the Soviet fleet, because of a technical issue, went unintentionally to ashore on the Swedish coast. Although in the middle of the Cold War, the two governments could resolved incident quickly and in a non-dramatic fashion.

Would the same outcome have happened if neutral Sweden were instead a member of NATO? It’s not too late for Sweden to come back to that geopolitical stance. Better secured in its own neutral port, than navigating in waters of confrontation.

Professor Marcello Ferrada de Noli is founder of Swedish Doctors for Human Rights and chief-editor of the geopolitical magazine The Indicter.

* A shortened version of this article “Därför behöver Sverige folkomröstning om NATO frågan” (in Swedish), was later published in Globalpolitics.