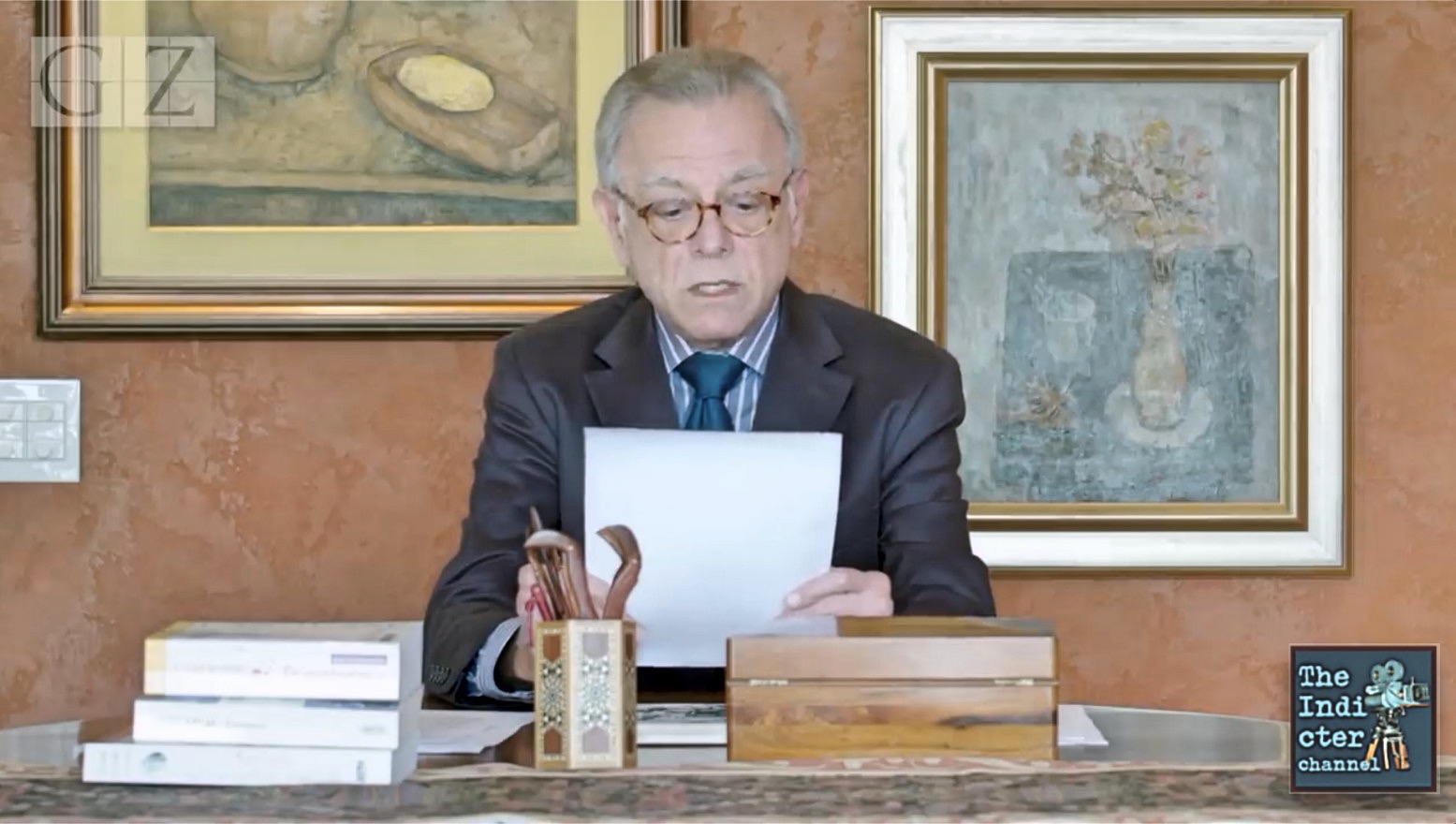

Statement by Brazilian diplomat Jose Bustani, OPCW first director-genera, at the meeting of the UN Security Council conveyed to discuss the Syrian chemical dossier and the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons.

TRANSCRIPT

Mr Chairman, Ambassador Vassily Nebenzia, your excellencies, distinguished delegates, ladies and gentlemen,

My name is José Bustani. I am honoured to have been invited to present a statement for this meeting of the UN Security Council to discuss the Syrian chemical dossier and the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. As the OPCW’s first Director General, a position I held from 1997 to 2002, I naturally retain a keen interest in the evolution and fortunes of the Organisation. I have been particularly interested in recent developments regarding the Organisation’s work in Syria.

For those of you who are not aware, I was removed from office following a US-orchestrated campaign in 2002 for, ironically, trying to uphold the Chemical Weapons Convention. My removal was subsequently ruled to be illegal by the International Labour Organisation’s Administrative Tribunal, but despite this unpleasant experience the OPCW remains close to my heart. It is a special Organisation with an important mandate. I accepted the position of Director General precisely because the Chemical Weapons Convention was non-discriminatory. I took immense pride in the independence, impartiality, and professionalism of its inspectors and wider staff in implementing the Chemical Weapons Convention. No State Party was to be considered above the rest and the hallmark of the Organisation’s work was the even-handedness with which all Member States were treated regardless of size, political might, or economic clout.

Although no longer at the helm by this time, I felt great joy when the OPCW was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2013 “for its extensive efforts to eliminate chemical weapons”. It was a mandate towards which I and countless other former staff members had worked tirelessly. In the nascent years of the OPCW, we faced a number of challenges, but we overcame them to earn the Organisation a well-deserved reputation for effectiveness and efficiency, not to mention autonomy, impartiality, and a refusal to be politicised. The ILO decision on my removal was an official and public reassertion of the importance of these principles.

More recently, the OPCW’s investigations of alleged uses of chemical weapons have no doubt created even greater challenges for the Organisation. It was precisely for this kind of eventuality that we had developed operating procedures, analytical methods, as well as extensive training programmes, in strict accordance with the provisions of the Chemical Weapons Convention. Allegations of the actual use of chemical weapons were a prospect for which we hoped our preparations would never be required. Unfortunately, they were, and today allegations of chemical weapons use are a sad reality.

It is against this backdrop that serious questions are now being raised over whether the independence, impartiality, and professionalism of some of the Organisation’s work is being severely compromised, possibly under pressure from some Member States. Of particular concern are the circumstances surrounding the OPCW’s investigation of the alleged chemical attack in Douma, Syria, on 7 April 2018. These concerns are emanating from the very heart of the Organisation, from the very scientists and engineers involved in the Douma investigation.

In October 2019 I was invited by the Courage Foundation, an international organisation that ‘supports those who risk life or liberty to make significant contributions to the historical record’, to participate in a panel along with a number of eminent international figures from the fields of international law, disarmament, military operations, medicine, and intelligence. The panel was convened to hear the concerns of an OPCW official over the conduct of the Organisation’s investigation into the Douma incident.

The expert provided compelling and documentary evidence of highly questionable, and potentially fraudulent conduct in the investigative process. In a joint public statement, the Panel was, and I quote, ‘unanimous in expressing [its] alarm over unacceptable practices in the investigation of the alleged chemical attack in Douma’. The Panel further called on the OPCW, ‘to permit all inspectors who took part in the Douma investigation to come forward and report their differing observations in an appropriate forum of the States Parties to the Chemical Weapons Convention, in fulfilment of the spirit of the Convention.’

I was personally so disturbed by the testimony and evidence presented to the Panel, that I was compelled to make a public statement. I quote: “I have always expected the OPCW to be a true paradigm of multilateralism. My hope is that the concerns expressed publicly by the Panel, in its joint consensus statement, will catalyse a process by which the Organisation can be resurrected to become the independent and non-discriminatory body it used to be.”

The call for greater transparency from the OPCW further intensified in November 2019 when an open letter of support for the Courage Foundation declaration was sent to Permanent Representatives to the OPCW to, ‘ask for [their] support in taking action at the forthcoming Conference of States Parties aimed at restoring the integrity of the OPCW and regaining public trust.’

The signatories of this petition included such eminent figures as Noam Chomsky, Emeritus Professor at MIT; Marcello Ferrada de Noli, Chair of the Swedish Doctors for Human Rights; Coleen Rowley, whistle-blower and a 2002 Time Magazine Person of the Year; Hans von Sponeck, former UN Assistant Secretary-General; and Film Director Oliver Stone, to mention a few.

Almost one year later, the OPCW has still not responded to these requests, nor to the ever-growing controversy surrounding the Douma investigation. Rather, it has hidden behind an impenetrable wall of silence and opacity, making any meaningful dialogue impossible. On the one occasion when it did address the inspectors’ concerns in public, it was only to accuse them of breaching confidentiality. Of course, Inspectors – and indeed all OPCW staff members – have responsibilities to respect confidentiality rules. But the OPCW has the primary responsibility – to faithfully ensure the implementation of the provisions of the Chemical Weapons Convention (Article VIII, para 1).

The work of the Organisation must be transparent, for without transparency there is no trust. And trust is what binds the OPCW together. If Member States do not have trust in the fairness and objectivity of the work of the OPCW, then its effectiveness as a global watchdog for chemical weapons is severely compromised.

And transparency and confidentiality are not mutually exclusive. But confidentiality cannot be invoked as a smoke screen for irregular behaviour. The Organisation needs to restore the public trust it once had and which no one denies is now waning. Which is why we are here today.

It would be inappropriate for me to advise on, or even to suggest how the OPCW should go about regaining public trust. Still, as someone who has experienced both rewarding and tumultuous times with the OPCW, I would like to make a personal plea to you, Mr Fernando Arias, as Director General of the OPCW. The inspectors are among the Organisation’s most valuable assets. As scientists and engineers, their specialist knowledge and inputs are essential for good decision making. Most importantly, their views are untainted by politics or national interests. They only rely on the science. The inspectors in the Douma investigation have a simple request – that they be given the opportunity to meet with you to express their concerns to you in person, in a manner that is both transparent and accountable.

This is surely the minimum that they can expect. At great risk to themselves, they have dared to speak out against possible irregular behaviour in your Organisation, and it is without doubt in your, in the Organisation’s, and in the world’s interest that you hear them out. The Convention itself showed great foresight in allowing inspectors to offer differing observations, even in investigations of alleged uses of chemical weapons (paras 62 and 66 of Part II, Ver. Annex). This right, is, and I quote, ‘a constitutive element supporting the independence and objectivity of inspections’. This language comes from Ralf Trapp and Walter Krutzsch’s “A commentary on Verification Practice under the CWC”, published by the OPCW itself during my time as DG.

Regardless of whether or not there is substance to the concerns raised about the OPCW’s behaviour in the Douma investigation, hearing what your own inspectors have to say would be an important first step in mending the Organisation’s damaged reputation. The dissenting inspectors are not claiming to be right, but they do want to be given a fair hearing. As one Director General to another, I respectfully request that you grant them this opportunity. If the OPCW is confident in the robustness of its scientific work on Douma and in the integrity of the investigation, then it has little to fear in hearing out its inspectors. If, however, the claims of evidence suppression, selective use of data, and exclusion of key investigators, among other allegations, are not unfounded, then it is even more imperative that the issue be dealt with openly and urgently.

This Organisation has already achieved greatness. If it has slipped, it nonetheless still has the opportunity to repair itself, and to grow to become even greater. The world needs a credible chemical weapons watchdog. We had one, and I am confident, Mr Arias, that you will see to it that we have one again.

Thank you.

Video excerpt:

You may also like

-

Part 4. SWEDHR analyses on the Khan Shaykhun and Sarmin allegations by the White Helmets were correct and verifiable. Debunking Kragh’s & Shyrokykh’s disinformation

-

Poltava’s geopolitical aftermath and the warmongering of Swedish elites

-

Aims Sweden to be a superpower in the Baltic Region?

-

Sweden’s “neutrality” at the service of Nazi Germany

-

The Indicter Magazine reaches half million viewers