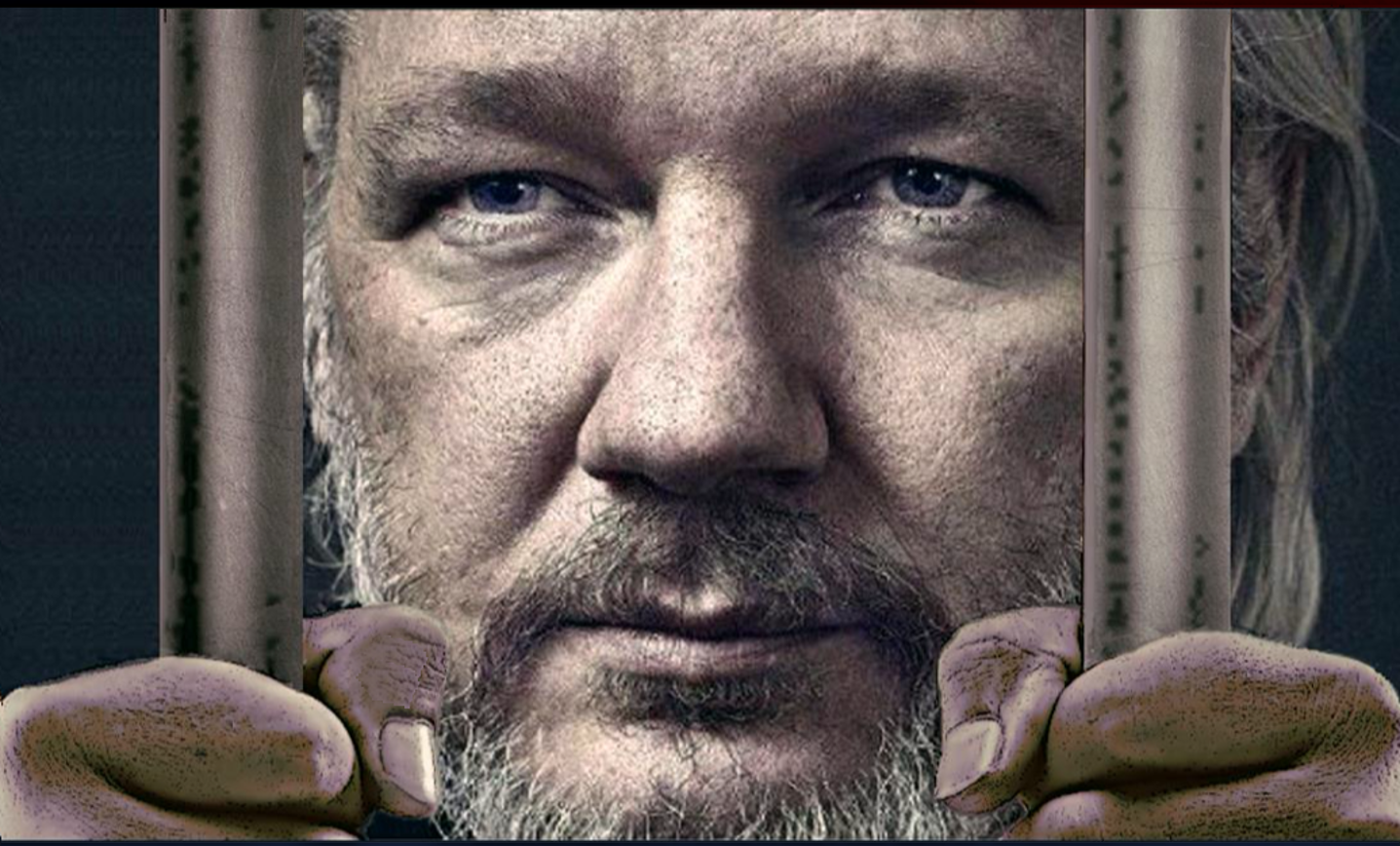

Featured December 2020, Human Rights Day edition

Nina Cross: Assange’s persecution has exposed the extremes to which our country’s public officials and authorities can be politically compromised. Our courts are demeaned, as are our public institutions. They are supposed to be accountable to us but instead appear hijacked, no less than instruments of US lawfare. If we allow our authorities to bend to US pressure to destroy Assange we will be consenting to our own destruction.

By Nina Cross

There are just weeks until Vanessa Baraitser, Magistrate at Westiminster Magistrates Court, rules on the extradition of Julian Assange, founder of Wikileaks. There is a catalogue of reasons why a lawful Britain with uncompromised courts and political leaders would not just block extradition but would have allowed Assange to walk free from the Ecuadorian embassy years ago. But the spirit of the law in the UK has faded under the crushing weight of US imperialism.

Assange’s extradition hearing in September in the Old Bailey showed how the prosecution case is built on desperation and extremes. Prosecuting a journalist for publishing evidence of wars crimes is an extreme political act leading to unprecedented levels of intolerance of speech and press freedom. This is reason to block extradition.

Assange almost certainly faces years of extreme solitary confinement and ill treatment if extradited. Warnings have come from the UN Human Rights Commission, the UN Rapporteur on Torture, civil societies and experts on the US prison system that he will be treated inhumanely, almost definitely subjected to Special Administrative Measures (SAMS). A template for this ill- treatment can be seen in the case of Fahad Hashmi, who was extradited from the UK to the US in 2007 and placed in SAMS resulting in extreme solitary confinement, as documented here by a former UN Rapporteur and civil societies. The UN Convention against Torture states ;

No State Party shall expel, return (“refouler”) or extradite a person to another State where there are substantial grounds for believing that he would be in danger of being subjected to torture.

This is reason to block extradition.

Assange has born the effect of abusive treatment for years. The medical testimonies that were given during his extradition hearing in September were filled with examples of extremes and revealed the chronic and debilitating health problems that years of arbitrary detention, human rights violations and inhumane treatment have caused him to suffer. Another reason to block extradition.

The September hearings revealed the harsh isolation regime deliberately inflicted upon Assange in the NHS health provision in high security Belmarsh prison, and the circumventing by authorities of standard procedures designed to protect isolated prisoners.

They revealed a calculated attempt to assassinate Assange’s character and integrity by painting him as a malingering hypochondriac who might nevertheless muster the reserves not to commit suicide if extradited. Those of us who have been watching recognised this as the continuing torture of a journalist.

The following, based on revelations from the hearing, is a closer look at how basic rules and norms designed to prevent suffering appear to have been side-stepped in Belmarsh by authorities supposedly charged with duty of care, resulting in Assange’s increased psychological torment and therefore risk to his life.

Revelations from the medical sessions of Assange’s extradition hearing

It was revealed that the head of Belmarsh healthcare, Dr Rachel Daly had informed the prosecution medical witness Dr Peter Blackwood that Assange was placed in isolation in Belmarsh healthcare unit to protect prison officials from embarrassment following the release of video footage of Assange taken by a prisoner. Blackwood said the governor was concerned about ‘reputational damage’.

But Assange’s defence showed that there had been a serious medical reason for Assange’s move to healthcare:

It was revealed that Daly did not report this to Blackwood:

According to reports of Blackwood’s testimony, it appears that at some point Assange was told he was in isolation for administrative reasons:

It was revealed that Assange’s mental health deteriorated under this administrative isolation:

These revelations raise serious questions about transparency and procedure. How could Assange be kept in deliberate isolation and in an NHS prison healthcare unit for so long and who had oversight as his condition was seen to deteriorate? Aside from questions around transparency, placing someone in effective prolonged solitary confinement in case they are filmed by another prisoner must be recognised as unacceptable and abusive.

Circumventing the treaty against torture

Official segregation of a prisoner is allowed under prison rule 45. It states that the removal of a prisoner from association can be enforced:

“45.—(1) Where it appears desirable, for the maintenance of good order or discipline or in his own interests, that a prisoner should not associate with other prisoners, either generally or for particular purposes, the governor may arrange for the prisoner’s removal from association accordingly.

There are procedures that must be applied to all isolation practices, official and unofficial:

There should be clear, transparent procedures in place to guide the decision to isolate detainees, which should only happen in exceptional circumstances.

Procedures are subject to scrutiny by the National Preventive Mechanism (NPM). Under the Optional protocol to the convention against torture (OPCAT) the NPM’s remit is to prevent ill‐treatment of people in detention.

The NPM defines isolation as

The physical isolation of individuals who are confined to cells or rooms for disciplinary, protective, preventive or administrative reasons, or who by virtue of the physical environment or regime find themselves largely isolated from others. Restrictions on social contacts and available stimuli are seldom freely chosen and are greater than for the general detainee population.

- Evidence should be provided to demonstrate that alternatives to isolation have been considered.

- Detainees at significant risk of suicide or self‐harm should not be held in isolation other than in exceptional circumstances which are clearly documented, for the minimum time necessary, regularly and substantively reviewed and authorised by the most senior manager in the institution.

The NPM fulfils its remit through the organisations that monitor or inspect places where people are detained. For HMP Belmarsh these involve The Independent Monitoring Board (IMB) (monitors are volunteers) and HM Inspectorate of Prisons.

The IMB becomes involved when a prisoner is placed in isolation for administrative reasons because:

- Removal from association is an administrative measure, not a punishment. This explains why there is no quasi-legal process (as for adjudications) and no appeal possible. There is no outside scrutiny of the use of R45/49/40 apart from that by the IMB or HMIP during an inspection. It is therefore important for Board members to speak to those held under these rules and attend the Reviews held in prisons when possible to check that the segregation decision is fair, that due process is followed, and that the total time spent segregated is not excessive.

There exists a memorandum of understanding between the IMB and the prison authorities that states the prison will contact the IMB regarding:

Any prisoner transferred to the segregation unit or equivalent;

Any review of a segregated prisoner under Rule 45, giving sufficient time to allow the member to attend;

It states that the prison may refuse access to records if they are protected or classified, and this is authorised by a senior official in the Ministry. The question here is – are the authorities protecting themselves from the IMB? Has the government placed Assange out of reach of those committed to prevent the torture and ill-treatment of prisoners?

It also states the prison will notify the IMB of:

a) Prisoners who have been subjected to close monitoring in accordance with

suicide and self-harm prevention policies (Assessment Care in Custody

Teamwork);

Here we ask – did Belmarsh officials send the IMB a notification that Assange was being monitored under suicide and self-harm prevention policies or was this risk to his life not disclosed to them?

Responding to an FOI request the IMB answered that they are only advised by Belmarsh prison of prisoners placed in the segregation unit, a further indication that Assange was denied normal process during isolation.

We are left to assume that last year Assange was placed in Belmarsh healthcare unit for a serious health condition. Once there, he was held under a prolonged and deliberate isolation regime where scrutiny by the torture prevention mechanisms was avoided.

It was revealed Assange’s health deteriorated while in isolation for ‘administration reasons’ in the healthcare unit

It was shown that Assange’s isolation in healthcare caused suffering and exacerbated his condition. This was made clear by Professor Michael Kopelman, medical expert witness of Assange’s legal team:

But Assange’s deterioration was also witnessed by professionals working there, as acknowledged by the prosecution medical witness Blackwood:

Professor Kopelman identified that isolation exacerbated Assange’s pain:

And yet Assange remained in the healthcare unit under the supervision of those charged with his care. Assange’s lengthy isolation in the healthcare unit clearly violates several UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners including indefinite and prolonged isolation. It raises questions about transparency, duty of care and legitimacy.

How Assange left the healthcare unit

During Assange’s isolation in the unit, which continued for several months, it was reported by his visitors and family that he was not allowed any contact with other prisoners, that corridors were cleared of inmates when he was escorted around the prison, and that isolation in the healthcare unit resulted in a devastating difficulty in accessing his lawyers. Assange was reported to spend more than 22 hours in his cell while in the healthcare unit, which under rule 44 of the UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners amounts to solitary confinement.

It was not through the intervention of professionals or officials that ended Assange’s isolation. This was the result of campaigning by inmates who petitioned the governor three times for his release from isolation.

It appears that Assange’s isolation for “administrative reasons” over several months, during which his health deteriorated, bypassed the scrutiny of torture prevention mechanisms. Instead, we see that his relocation resulted from the intervention of inmates who in effect took up the cause of torture prevention and fulfilled the OPCAT remit on behalf of the UK authorities.

Propaganda of “relative isolation” in the healthcare unit

The prosecution attempted to downplay Assange’s psychological torment resulting from the isolation inflicted on him in the healthcare unit. Blackwood claimed that had Assange’s depression been severe he would have been treated outside of Belmarsh.

Blackwood described Assange’s isolation as “relative”. Relative to what exactly? And can the severity of depression be reliably and independently diagnosed on the basis of how the depressed person has until now been treated and how their condition has been perceived?

In fact, it is possible to argue that Assange was more cut off from meaningful human contact by being held in ‘relative isolation’ in Belmarsh healthcare unit than he was likely to be either in Belmarsh’s segregation unit or in a hospital away from the arbitrary practices of that prison.

We know from reports that in Belmarsh segregation unit it is possible to have more contact with family, both in the form of visits and telephone calls. This was made evident during the detention there last year of Tommy Robinson (real name Stephen Yaxley-Lennon, founder of the English Defence League). Robinson was convicted for breaching contempt of court laws for streaming the trial of a sex trafficking grooming gang on Facebook Live outside Leeds court in 2018, and was later convicted as a civil prisoner. Robinson’s imprisonment there appeared to fall under the Belmarsh category of prisoner “requiring specific management arrangements because of their public and media profile”. There he was allowed unlimited phone calls everyday for 2 hours, and 3 to 4 visitors each week. On one occasion the governor personally intervened to enable a journalist to visit him on a day not normally scheduled for his visits.

Assange’s status changed to that of an unconvicted prisoner in October 2019, supposedly making him eligible to have all of the family contact Robinson was allowed as well as additional rights. Instead, his unconvicted prisoner status was meaningless and he was arbitrarily held in what amounts to indefinite isolation which exacerbated his depression and suicidal urges, watched by those charged with his care.

Despite being in a general wing since January, under current Covid-19 prison regime restrictions Assange is now in virtual permanent solitary confinement. Known to have a chronic lung condition, he is at risk of complications or death if he catches the Coronavirus. Calls for his release are seen daily from across the globe. This week marks the 10th anniversary of his arbitrary detention, and another statement by the UN Rapporteur on Torture, Nils Melzer, warning of risks to Assange’s life and listing violations of international law once more shames the British authorities.

What holds the house of cards together is silence. The authorities rely on complicity of those inside the public institutions, those who need the pay cheque, those who have signed the official secrets act, those who fear repercussions if they tell. But we know it only takes a few to bring the house down. We know the power of whistleblowers. That’s why Assange is in Belmarsh prison fighting for his life.

You may also like

-

Global Assange Amnesty Network (GAAN) call upon Amnesty International to declare Julian Assange a Prisoner of Conscience retroactively

-

“Assange was saved by the U.S. presidential race” – But, can he feel safe?

-

Nomination of Julian Assange for Nobel Peace Prize 2023

-

Assange Loses, High Court Allows US Appeal; Quashes Assange’s Discharge

-

New FOI responses confirm the British government’s media campaign against Julian Assange