By Marcello Ferrada de Noli, professor emeritus of epidemiology. Formerly at Karolinska Institute, Sweden, and Harvard Medical School. Chair, Swedish Doctors for Human Rights SWEDHR

The elderly have comprised the vast majority of Covid-19 fatalities in Sweden, either dying in care homes or their own residence, often alone. By mid-May 2020, only 13 percent of the care home victims had received treatment at Swedish hospitals. In August 2020, only five percent of the Covid-19 patients admitted for treatment at Swedish hospitals came from care home facilities. Sweden has by far the highest proportion of deaths among confirmed Corona cases in the Nordic countries. This article looks into the possible reasons why.

Anders Tegnell, the architect of the Swedish Coronavirus strategy, relaxing at an outdoor bar in Stockholm, 28 May 2020. By that time, Sweden had recorded the highest Covid-19 deaths per capita in Europe. Photo Aftonbladet.

Herd immunity

International comparisons of the covid-19 situation may help to assess the efficacy of the different strategies used by developed countries’ health authorities. Such strategies may have been assimilated by some countries formerly known as ‘third world’ because of continued economic dependency; the praxis of attributing superior technical know-how in matters of public health to countries seen as more economically developed still exists in some governing circles. For this reason, populations in Latin America and Africa and other regions have been ruthlessly targeted with propaganda by developed countries promoting their epidemiological methods.

In Europe, Italy was the first country to apply the “lockdown” approach. At the start of the ‘second wave’ it had one of the lowest incidences of new Covid-19 cases. The model presented as alternative is “herd immunity”, most associated with Sweden’s neoliberal interpretation of it. The idea here is to prioritize the economy: no closing factories, schools, or restaurants. Sweden’s Public Health Agency chief epidemiologist Anders Tegnell said, “if we close the schools we would lose 25 % of the labour force” (parents would have to stay at home). He has also stated, “herd immunity is the one thing which eventually will stop the spread of this virus”. In the words of Johan Giesecke, the Agency’s senior adviser, herd immunity strategy would consist of “letting the virus pass through the population”. Even in email by Tegnell to his Finland’s counterpart Mika Salminen, he writes”“One point would be to keep schools open to reach herd immunity faster.” (15 March 2020).

In response to the international criticism that ensued –to which The Indicter contributed with some early analyses– the Swedish government tried to distance itself from the term but in practice the strategy has not changed. Sweden’s ambassador to the US declared that “Stockholm could reach herd immunity by May”. However, five months’ later this has not been achieved, and Sweden’s economy has suffered just as much, if not worse, than its neighbours who used lockdown measures.

The epidemiological indicators I present below expose the flawed, not to say macabre, effects of the Swedish exporting model. The message to other nations is: Don’t buy it. Survive instead.

Case Fatality Rate, CFR

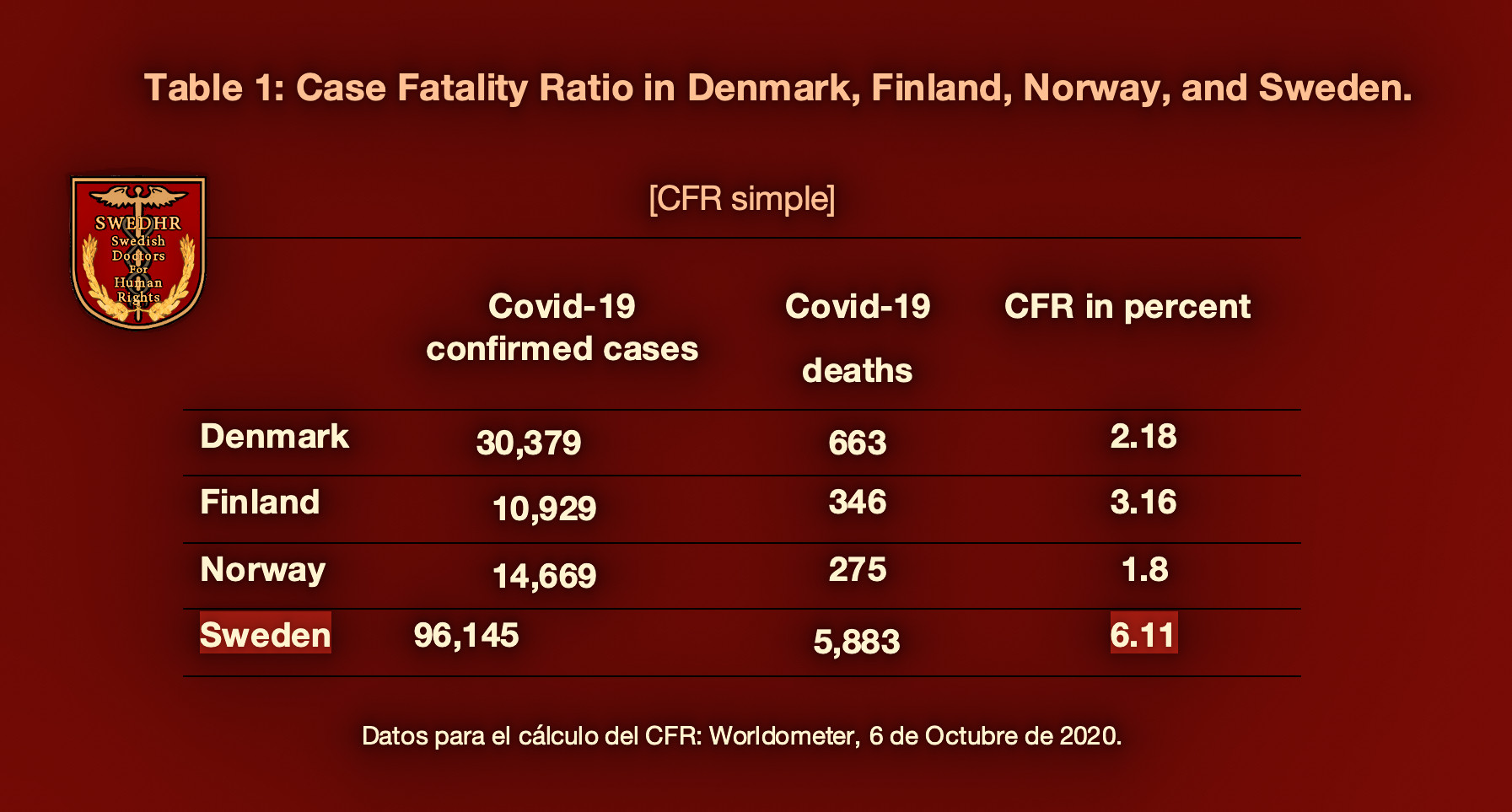

Based on current international data, I have carried out a comparison of mortality indicators between Nordic countries that applied forms of lockdown, and Sweden.

There certainly are multiple models for such international epidemiological comparisons. However, I start with the simple method to determine whether there is a statistical significance in the reported differences regarding total number, number per capita, etc. (As we know, not all differences in mortality rates are epidemiologically/statistically significant, although they can appear as such in media reports).

Results found through comparisons between the number of Covid-19 deaths in Sweden (n = 5,883) and ditto the total numbers in Denmark, Finland and Norway (n = 1,284), give a significant overrepresentation of the Swedish deaths (X2 = 3023.3239, p = <0.00001). The difference is thus highly statistically significant.

Another method is the Case Fatality Rate (hereinafter referred to as CFR). CFR intends to estimate the proportion of deaths among confirmed cases. It shows the proportion of those who were ill and who eventually died, and WHO considers it as “a measure of severity among detected cases”. Among more than 200 countries included in the international tables on Corona, Sweden is currently ranked 14th out of the 15 countries with the highest Covid-19 death rate per 1 M population. However, when CFR is taken into account, Sweden increases to 6th place in that group, illustrating the significance of the CFR method. This ranking position has remained rather even for Sweden. My calculation (as of 7 October 2020) indicates the same results established in a research paper from May 2020.

Covid-19 case fatality rate in Sweden and neighbouring countries

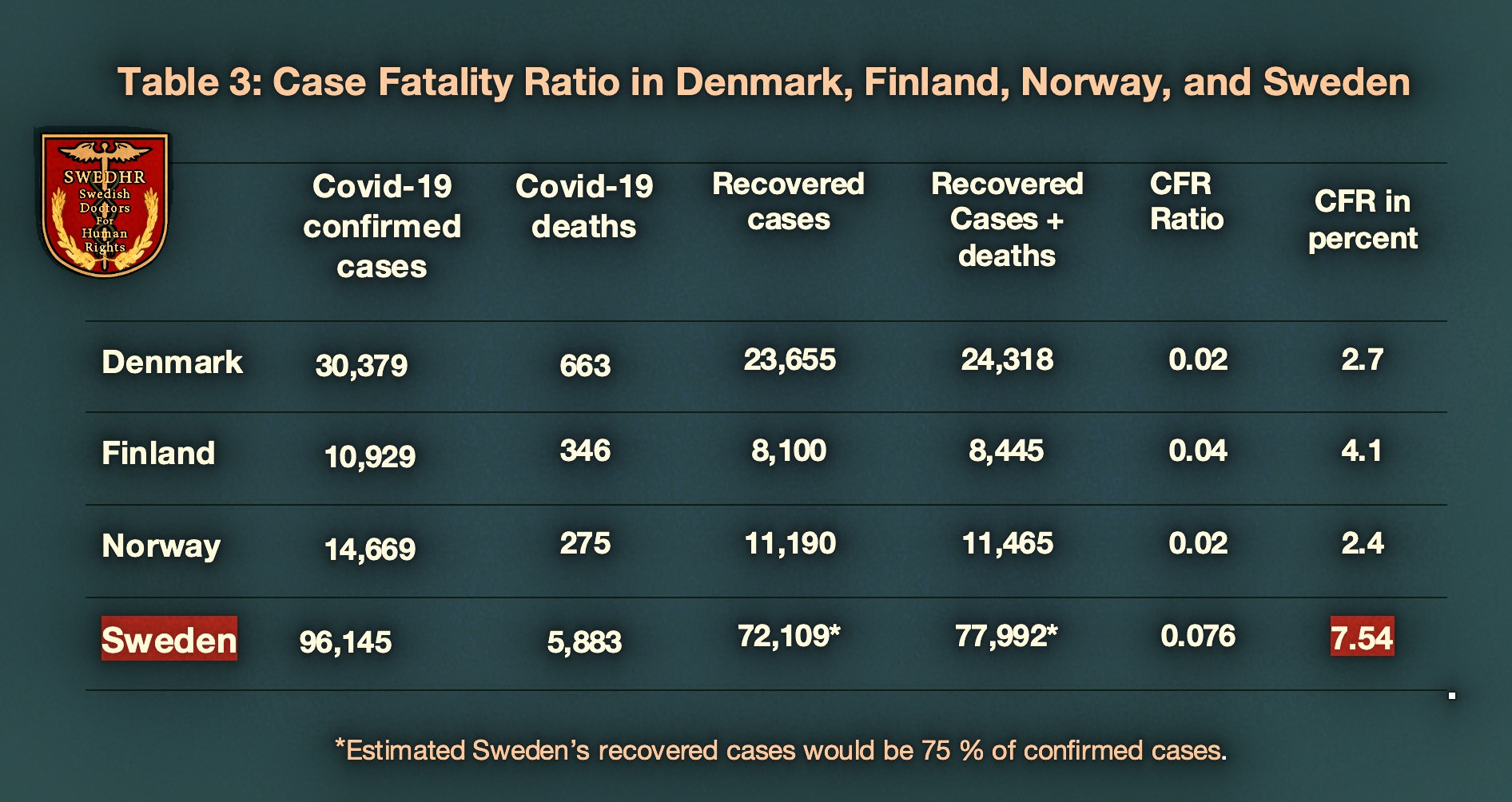

Regarding the comparison among the said Nordic countries, I have used two CFR calculation models. One is the usual CFR, which only needs the death toll and the number of reported Covid-19 patients. The second consists of a more refined method, also recently described by the WHO, which in addition requires the number of cases that have recovered from the disease.

With the first method, the current CFR calculation results in: Denmark 2.18, Finland 3.16, Norway 1.8, and Sweden 6.11 percent.

Furthermore, according to the WHO, the CFR may result underestimated when delays in reporting deaths occur, which is the case for Sweden, as demonstrated by a recent article authored by nine Swedish researchers.

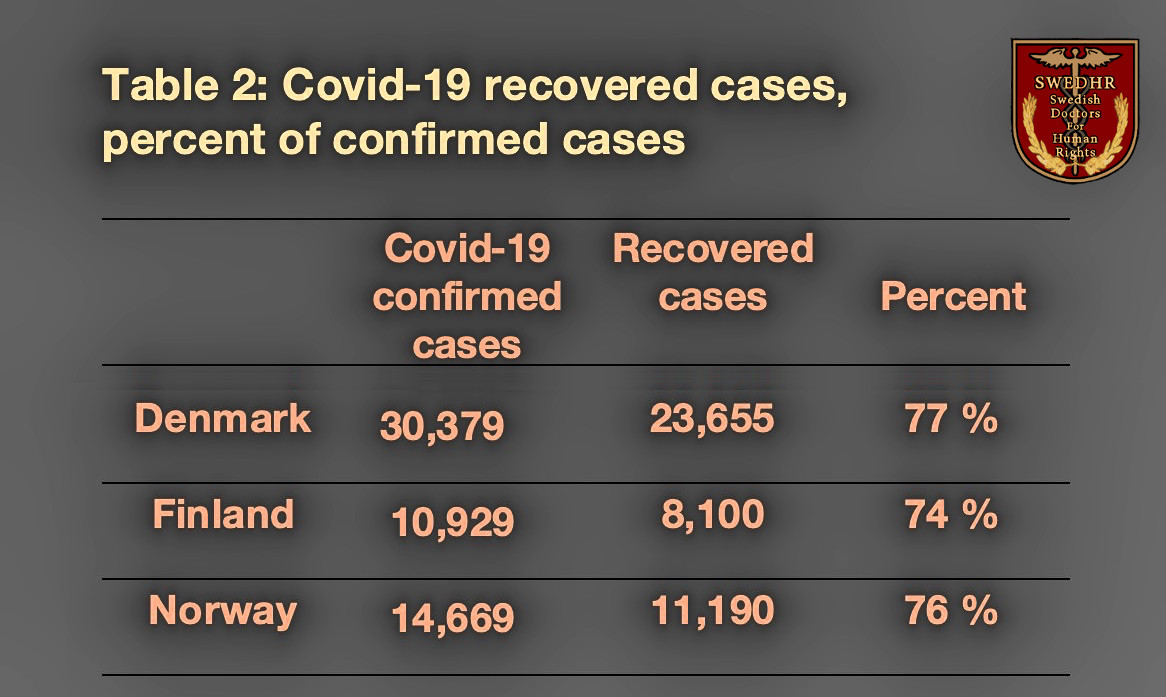

So, even if Sweden’s above-mentioned CFR appears definitely higher than that of neighbouring countries, it could be even higher when considering the bias mentioned by WHO.The second CFR model consists of a calculation which also includes the number of recovered cases. The question is, could that calculation accurately be applied in the international comparison that includes Sweden? The answer would be no. At least not officially. This is because Sweden does not report data regarding such cases internationally. Why not? Because in the first place – according to the explanation given by Sweden’s National Board of Health and Welfare (Socialstyrelsen) – they do not even keep a record of the total number of the country’s recovered cases.

This was the reply I received from the Statistic Coordinator at Sweden’s National Board of Health and Welfare (Socialstyrelsens Statisksamordnade), who emailed me on 6 October 2020: “Socialstyrelsen does not have an estimate of the overall number of recovered cases of Covid-19”.

However, there are two findings that would help to approximately estimate Sweden’s missing (or unreported) number of recovered cases. First is the percentage of cases confirmed world-wide that have recovered, which is 75%, thus providing a 75% average. The second finding shows that the number of recovered from confirmed cases in the Nordic countries neighbouring Sweden also gives an average of 75%.

Therefore, I would estimate the number of recovered cases in Sweden to be 75 percent of the total confirmed cases in the country (n= 96,145), which gives n= 72,109. The results of this new CFR according to the WHO recommendation is then: Denmark 2.7 %, .Finland 4.1 %, Norway 1.4 %, and Sweden 7,5 %.

What is behind the high Swedish Covid-19 CFR?

In Sweden, most of the covid-19 victims were 70 years or older. By June 2020, half of those individuals (n=2036) were known to be living in nursing homes, with a further number (n= 1062) in the home-care system, or in residences where many victims lived alone. . Only 13 percent of the care home victims had received treatment at Swedish hospitals by mid-May. By August, Covid-19 care-home residents made up only a five percent of such patients treated at hospitals.

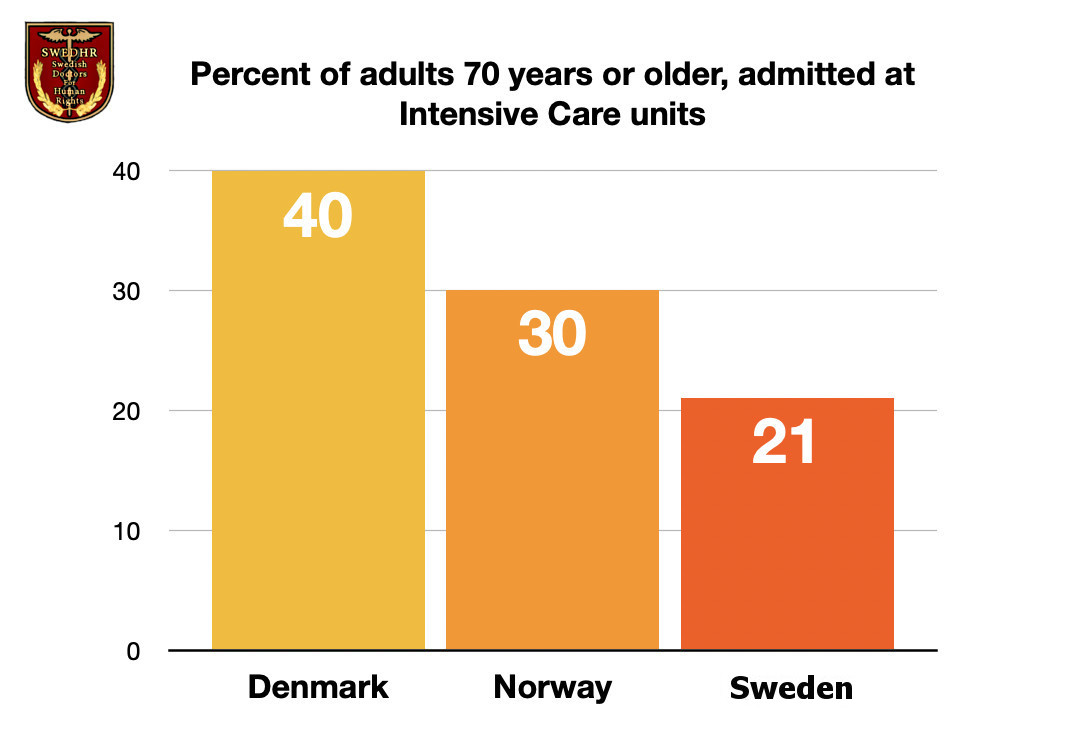

While in Denmark, half of Covid-19 patients over 70 were admitted to intensive care, and in Norway 30% were admitted, in Sweden only 21% of the same age group received access. Health authorities in Sweden issued a directive stipulating certain groups of patients should be left out of intensive care. These included: those over 80 years of age, those over 70 years of age with one significant illness and those between 60 and 70 years of age with at least two organ diseases including heart, lung and kidney.

Ensuing, in May 2020, Karolinska Hospital reported that only 80 % of IVA places at Karolinska Hospital were occupied. This prompted Swedish TV to broadcast it as “very positive”, while Aftonbladet wondered whether “we are making it better than in other countries”. Meanwhile scores of Swedish elderly had been denied treatment at those intensive care facilities.

In its definition, epidemiology strives to identify both the risk factors that can lead to the morbidity / mortality of the disease and the population groups that are particularly exposed. As an explanation for Sweden’s disproportionate Covid-19 mortality among the elderly, the General Director of the Swedish Public Health Agency’s Johan Carlson declared that chief epidemiologist Anders Tegnell has no responsibility in “what has happened in elderly care” in Sweden, which [instead] “is a consequence of a neglected structure and preparedness”.

Thus, the elderly were a known risk group, including for the spread of the virus. Why then was that “structural” problem not taken into account in the architecture of the Swedish Covid-19 strategy from the beginning? For example, why was the national directive on nursing homes (from 1 April 2020) so delayed? A few weeks later, it became known that nursing homes in 81% of Sweden’s municipalities “had confirmed or suspected cases of Covid-19”.

Are Sweden’s Covid-19 mortality statistics comparable?

Swedish epidemiologists would try to explain that Covid-19 mortality statistics for Sweden are difficult or not accurate, for international comparisons because the number of actual individuals with the disease should be estimated higher that the confirmed cases, like in the case of Infection Mortality Rate (IMR). But then, why has Sweden’s testing for Covid-19 been the lowest among its Nordic neighbouring countries, and also low in comparison with European countries? Is Covid-19 testing in Sweden incompatible with other countries?

Nevertheless, regarding testing, logic’s answer is simple: Reducing the number of tests means fewer opportunities to detect those with the disease. Which is not the same as assuming that those diseased individuals do not exist. Indeed they do exist, and they are contagious. However, the ‘gain’ here about this is that we had a smaller number of new cases to report. Hence, a real public health problem is turned into a tool to cover a flawed epidemiological strategy.

What we do need?

Don’t follow the herd immunity model. To decimate SARS-cov-2 what we do need is a vaccine. What countries in disarray need is to start with available vaccination programs.

By adopting a Swedish public-health model you may be serving a political establishment whose remits are greed, corporate economic power, and adherence to its own interpretation of what democracy should mean. For what is democracy in the context of this debate? Who shall ultimately decide the domestic strategy of a problem threatening the life of every single citizen of a country?

Democratic decisions are built on the participation of all, and in the interests of all, ensuring all voices are heard. In my experience, this is not the case in Sweden. The publication of these findings was declined by Swedish mainstream newspapers, despite the phenomenon of the high CFR in Sweden was not known, or been previously reported. They prefer, instead, to control discourse, permitting only mild criticism, which serves the authorities in the current Covid-19 debate. This new Ikea-wrapped neoliberal concept of democracy, should not be unpacked by countries in Latin-America, Africa and other latitudes. There, a dignified formula for democracy should preclude the Swedish praxis of how – without the participation of the dēmos (Greek for ‘people’), those in power exercise the kratos (id. for ‘rule’) to politically benefit themselves.